Sociological classifications of religious movements

The church-sect typology has its origins in the work of Max Weber and Ernst Troeltsch, and from about the 1930s to the late 1960s it inspired numerous studies and theoretical models especially in American sociology.

[5] Ernest Troeltsch accepted Weber's definition but added the notion of a varying degree of accommodation with social morality: the church is intrinsically conservative, inclined to seek for an alliance with the upper classes and aiming at dominating all elements within society, while the sect is in tension with current societal values, rejects any compromise with the secular order and tends to be composed of underprivileged people.

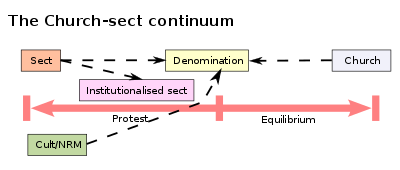

[6][7] Subsequent sociological and theological studies elaborated on Weber's and Troeltsch's typologies incorporating them into a theory of the church-sect "continuum" or "movement".

Sects are inherently unstable and as they grow they tend to become church-like; once they have become established institutions, marked by compromise and accommodation, they are in turn exposed to new schismatic challenges.

[4][11][7] Benton Johnson simplified the definition of sect and church and based it on a single variable: the degree of acceptance of the social environment.

[12][7] The theory suffered from lack of agreement on the distinguishing features, from proliferation of new types and from questionable empirical evidence on its core assumptions.

Both the church and the sect are hierocratic organisations as they enforce their orders through psychic coercion by providing or denying religious goods such as spiritual benefits (magical blessing, sacraments, grace, forgiveness, etc.)

[14]: 54 Unlike the sect, however, the church is a compulsory organisation whose membership is typically determined by birth or infant baptism rather than by voluntary association,[15]: 38 which claims "a monopoly on the legitimate use of hierocratic coercion.

"[14]: 54 Because of its claim to universal hierocratic domination, the church is inclined to level all non-religious distinctions and to overcome "household, sib and tribal ties ... ethnic and national barriers.

[1] The demands of the church towards the clergy can be more or less demanding but their full satisfaction – the holiness of the minister – is not a condition for the efficacy of the sacraments and for the performance of the religious rituals: the church fulfils its mission ex opere operato, and sharply distinguishes between persona and office, that is, between charisma of the individual minister, which may occasionally be lacking, and efficacy of the religious function, which is perpetual and depends on the will of God alone.

It consists of individuals whose conduct and life style "proclaim the glory of God," religiously qualified persons who believe (or hope) to be "called to salvation.

By contrast a "church," as a universalistic establishment of the salvation of the masses raises the claim like the "state," that everyone, at least each child of a member, must belong by birth.

Lay preaching and universal priesthood are the norm, as well as "direct democratic administration" by the congregation,[14]: 1208 which is jointly responsible for the celebration of the sacraments by a worthy minister in a state of grace.

[22]: 288 Calvinism is best characterized as a sect-like church; Baptists, Quakers and Methodists are paradigmatic cases of sects, as well as Christian Scientists, Adventists.

Hinduism, for example, is a strictly birth-religion, to which one belongs merely by being born to Hindu parents, but is exclusive as a sect because for certain religious offences one can be forever excluded from the community.

[23] As ideal types, church and sect do not describe reality and hardly can be found in pure form, but help us understand why people act the way they do by developing meaningful social theories.

[15]: 308 Finally, as voluntary associations of qualified people, sects maintain discipline: they select, probe and sanction their members, and are likely to have the greatest educative influence on individuals and through them the wider society.

[5] Weber argues that sect membership worked in the United States as "a certificate of moral qualification and especially business morals:"[17]: 305 Sects provided proof of one’s reputation, honesty and trustworthiness, and in doing so they became a vital source of "the bourgeois capitalist business ethos among the broad strata of the middle classes (the farmers included).".

Like Weber, Troeltsch stresses the "objective institutional character" of the church compared to the "voluntary community" of the sect, and distinguishes the "universal all-embracing ideal" of the church, its desire to control great masses of people, from the gathering of "a select group of the elect" by the sect, which is placed "in sharp opposition to the world.

[6] The sect emphasizes the eschatological features of Christian doctrine, which it interprets literally and in a radical manner; it is a small, voluntary fellowship of converts who seek to realize the divine law in their own behaviour, setting themselves apart from and in opposition to the world, and refusing to draw a sharp distinction between clergy and laity; it embraces ideals of frugality, prohibits participation in legal and political affairs, and appeals principally to the lower classes.

[6] In theology and liturgy, the sect refrains from bureaucratic dogmatism and ritualism and, compared to the church, it adopts a more inspirational, informal and unpredictable approach to preaching and worship.

Saudi Arabia, however, lacks Johnstone's criteria for an ordained clergy and a strictly hierarchical structure; however, it has the ulema and their Senior Council with the exclusive power of issuing fatwa,[27] as well as fiqh jurisprudence through the Permanent Committee for Scholarly Research and Ifta.

[28] Ecclesias include the above characteristics of churches with the exception that they are generally less successful at garnering absolute adherence among all of the members of the society and are not the sole religious body.

[citation needed] An often-seen result of such factors is the incorporation into the theology of the new sect a distaste for the adornments of the wealthy (e.g., jewelry or other signs of wealth).

Bruce Campbell discusses Troeltsch's concept in defining cults as non-traditional religious groups that are based on belief in a divine element within the individual.

[30] He gives three types of cults: Campbell discusses six groups in his analysis: Theosophy, Wisdom of the Soul, spiritualism, New Thought, Scientology, and Transcendental Meditation.

He argues that the influx of Eastern religious systems, including Taoism, Confucianism, and Shintoism, which do not fit within the traditional distinctions between church, sect, denomination, and cult, have compounded typological difficulties.