Solar flare

Solar flares are thought to occur when stored magnetic energy in the Sun's atmosphere accelerates charged particles in the surrounding plasma.

The extreme ultraviolet and X-ray radiation from solar flares is absorbed by the daylight side of Earth's upper atmosphere, in particular the ionosphere, and does not reach the surface.

[2] The plasma medium is heated to >107 kelvin, while electrons, protons, and heavier ions are accelerated to near the speed of light.

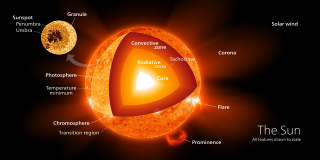

[2] Flares occur in active regions, often around sunspots, where intense magnetic fields penetrate the photosphere to link the corona to the solar interior.

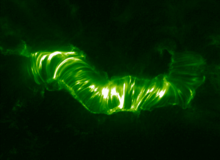

The unconnected magnetic helical field and the material that it contains may violently expand outwards forming a coronal mass ejection.

These loops extend from the photosphere up into the corona and form along the neutral line at increasingly greater distances from the source as time progresses.

[14] The existence of these hot loops is thought to be continued by prolonged heating present after the eruption and during the flare's decay stage.

[15] In sufficiently powerful flares, typically of C-class or higher, the loops may combine to form an elongated arch-like structure known as a post-eruption arcade.

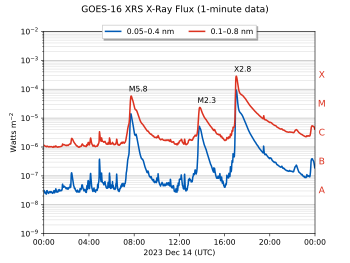

[19][20][21][22]: 23–28 The modern classification system for solar flares uses the letters A, B, C, M, or X, according to the peak flux in watts per square metre (W/m2) of soft X-rays with wavelengths 0.1 to 0.8 nanometres (1 to 8 ångströms), as measured by GOES satellites in geosynchronous orbit.

[29][30] The electromagnetic radiation emitted during a solar flare propagates away from the Sun at the speed of light with intensity inversely proportional to the square of the distance from its source region.

[33][34] Enhanced XUV irradiance during solar flares can result in increased ionization, dissociation, and heating in the ionospheres of Earth and Earth-like planets.

On Earth, these changes to the upper atmosphere, collectively referred to as sudden ionospheric disturbances, can interfere with short-wave radio communication and global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) such as GPS,[35] and subsequent expansion of the upper atmosphere can increase drag on satellites in low Earth orbit leading to orbital decay over time.

[36][37][additional citation(s) needed] Flare-associated XUV photons interact with and ionize neutral constituents of planetary atmospheres via the process of photoionization.

In the lower ionosphere where flare impacts are greatest and transport phenomena are less important, the newly liberated photoelectrons lose energy primarily via thermalization with the ambient electrons and neutral species and via secondary ionization due to collisions with the latter, or so-called photoelectron impact ionization.

When ionization is higher than normal, radio waves get degraded or completely absorbed by losing energy from the more frequent collisions with free electrons.

The Space Weather Prediction Center, a part of the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, classifies radio blackouts by the peak soft X-ray intensity of the associated flare.

During non-flaring or solar quiet conditions, electric currents flow through the ionosphere's dayside E layer inducing small-amplitude diurnal variations in the geomagnetic field.

These ionospheric currents can be strengthened during large solar flares due to increases in electrical conductivity associated with enhanced ionization of the E and D layers.

The subsequent increase in the induced geomagnetic field variation is referred to as a solar flare effect (sfe) or historically as a magnetic crochet.

The latter term derives from the French word crochet meaning hook reflecting the hook-like disturbances in magnetic field strength observed by ground-based magnetometers.

[44][better source needed] The impacts of solar flare radiation on Mars are relevant to exploration and the search for life on the planet.

Models of its atmosphere indicate that the most energetic solar flares previously recorded may have provided acute doses of radiation that would have been almost harmful or lethal to mammals and other higher organisms on Mars's surface.

[citation needed] During World War II, on February 25 and 26, 1942, British radar operators observed radiation that Stanley Hey interpreted as solar emission.

Because the Earth's atmosphere absorbs much of the electromagnetic radiation emitted by the Sun with wavelengths shorter than 300 nm, space-based telescopes allowed for the observation of solar flares in previously unobserved high-energy spectral lines.

[65] A physics-based method that can predict imminent large solar flares was proposed by Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research (ISEE), Nagoya University.