Space Shuttle abort modes

The three Space Shuttle main engines (SSMEs) were ignited roughly 6.6 seconds before liftoff, and computers monitored their performance as they increased thrust.

If an anomaly was detected, the engines would be shut down automatically and the countdown terminated before ignition of the solid rocket boosters (SRBs) at T = 0 seconds.

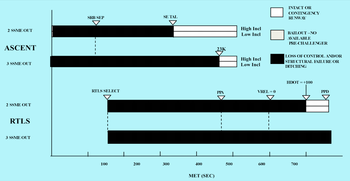

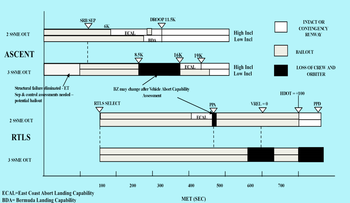

The shuttle would continue downrange to burn excess propellant, as well as pitch up to maintain vertical speed in aborts with a main-engine failure.

Cutoff and separation would occur effectively inside the upper atmosphere at an altitude of about 230,000 ft (70,000 m), high enough to avoid subjecting the external tank to excessive aerodynamic stress and heating.

[3] If a second main engine failed at any point during PPA, the shuttle would not be able to reach the runway at KSC, and the crew would have to bail out.

Prior to a shuttle launch, two sites would be selected based on the flight plan and were staffed with standby personnel in case they were used.

Additionally, two C-130 aircraft from the space flight support office from the adjacent Patrick Space Force Base (then known as Patrick Air Force Base) would deliver eight crew members, nine pararescuemen, two flight surgeons, a nurse and medical technician, and 2,500 pounds (1,100 kg) of medical equipment to Zaragoza, Istres, or both.

One or more C-21S or C-12S aircraft would also be deployed to provide weather reconnaissance in the event of an abort with a TALCOM, or astronaut flight controller aboard for communications with the shuttle pilot and commander.

An abort once around (AOA) was available if the shuttle was unable to reach a stable orbit but had sufficient velocity to circle Earth once and land at around 90 minutes after liftoff.

Therefore, taking this option because of a technical malfunction (such as an engine failure) was very unlikely, although a medical emergency on board could have necessitated an AOA abort.

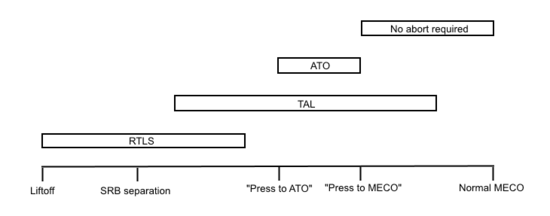

There was an order of preference for abort modes: Unlike with all other United States orbit-capable crewed vehicles (both previous and subsequent, as of 2024), the shuttle was never flown without astronauts aboard.

However, STS-1 commander John Young declined, saying, "let's not practice Russian roulette"[9] and "RTLS requires continuous miracles interspersed with acts of God to be successful.

The struts attaching the orbiter to the external tank were strengthened to better endure a multiple SSME failure during SRB flight.

Unlike the ejection seat in a fighter plane, the shuttle had an inflight crew escape system[12] (ICES).

The vehicle was put in a stable glide on autopilot, the hatch was blown, and the crew slid out on a pole to clear the orbiter's left wing.

While this at first appeared only usable under rare conditions, there were many failure modes where reaching an emergency landing site was not possible yet the vehicle was still intact and under control.

A second SSME almost failed because of a spurious temperature reading; however, the engine shutdown was inhibited by a quick-thinking flight controller.

High-inclination launches (including all ISS missions) would have been able to reach an emergency runway on the East Coast of North America under certain conditions.

[13] The sites were not staffed with NASA employees or contractors and the staff working there were given no special training to handle a shuttle landing.

If they were ever needed, the shuttle pilots would have had to rely on regular air traffic control personnel using procedures similar to those used to land a gliding aircraft that has suffered complete engine failure.

By the time Columbia flew again (STS-61-C, launched on January 12, 1986), it had been through a full maintenance overhaul at Palmdale and the ejection seats (along with the explosive hatches) had been fully removed.

[15]The Soviet shuttle Buran was planned to be fitted with the crew emergency escape system, which would have included K-36RB (K-36M-11F35) seats and the Strizh full-pressure suit, qualified for altitudes up to 30,000 metres (98,000 ft) and speeds up to Mach three.

[16] Buran flew only once in fully automated mode without a crew, thus the seats were never installed and were never tested in real human space flight.

In theory an ejection cabin could have been designed to withstand reentry, although that would entail additional cost, weight and complexity.

Cabin ejection was not pursued for several reasons: Source:[18] Predetermined emergency landing sites for the orbiter were chosen on a mission-by-mission basis according to the mission profile, weather and regional political situations.

Algeria Australia Bahamas Barbados Canada[25] Cape Verde Chile France The Gambia Germany Greece Iceland Ireland Jamaica Liberia Morocco New Zealand Portugal Saudi Arabia Spain Somalia South Africa Sweden Turkey United Kingdom British Overseas Territories United States Democratic Republic of the Congo Other locations In the event of an emergency deorbit that would bring the orbiter down in an area not within range of a designated emergency landing site, the orbiter was theoretically capable of landing on any paved runway that was at least 3 km (9,800 ft) long, which included the majority of large commercial airports.

In practice, a US or allied military airfield would have been preferred for reasons of security arrangements and minimizing the disruption of commercial air traffic.