Space capsule

Examples of new crew capsules currently in development include NASA's Orion, Boeing's Starliner, Russia's Orel, India's Gaganyaan, and China's Mengzhou.

The capsule was originally designed for use both as a camera platform for the Soviet Union's first spy satellite program, Zenit and as a crewed spacecraft.

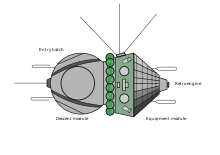

[2] The reentry module was completely covered in ablative heat shield material, 2.3 meters (7.5 ft) in diameter, weighing 2,460 kilograms (5,420 lb).

The cosmonaut sat in an ejection seat with a separate parachute for escape during a launch emergency and landing during a normal flight.

However, ionized gases in the plasma layer can also be used to create an artificial radio window, allowing communication signals to be transmitted and received despite the interference.

Vostok's ejection seat was removed to save space (thus there was no provision for crew escape in the event of a launch or landing emergency).

An airlock was needed because the vehicle's electrical and environmental systems were air-cooled, and complete capsule depressurization would lead to overheating.

The development of the Mercury capsule began in earnest after NASA selected the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation as its contractor in 1959.

[7] The Mercury spacecraft's principal designer was Maxime Faget, who started research for human spaceflight during the time of the NACA.

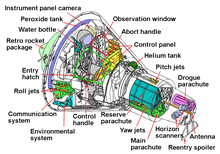

[9] It had a convex base, which carried a heat shield (Item 2 in the diagram below)[14] consisting of an aluminum honeycomb covered with multiple layers of fiberglass.

[21] Underneath the seat was the environmental control system supplying oxygen and heat,[22] scrubbing the air of CO2, vapor and odors, and (on orbital flights) collecting urine.

[23][n 1] The recovery compartment (4)[25] at the narrow end of the spacecraft contained three parachutes: a drogue to stabilize free fall and two main chutes, a primary and reserve.

The Soviets were able to launch a second Vostok on a one-day flight on August 6, before the US finally orbited the first American, John Glenn, on February 20, 1962.

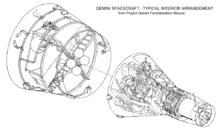

Unlike Mercury, Gemini used completely solid-state electronics, and its modular design made it easy to repair.

It was designed to test new techniques for orbital rendezvous and docking, but it also featured improvements in life support systems, spacecraft reentry, and other critical areas.

The tower was heavy and complicated, and NASA engineers reasoned that they could do away with it as the Titan II's hypergolic propellants would burn immediately on contact.

A Titan II booster explosion had a smaller blast effect and flame than on the cryogenically fueled Atlas and Saturn.

At higher altitudes, where the ejection seats could not be used, the astronauts would return to Earth inside the spacecraft, which would separate from the launch vehicle.

[38] The main proponent of using ejection seats was Chamberlin, who had never liked the Mercury escape tower and wished to use a simpler alternative that would also reduce weight.

He was also concerned about the astronauts being launched through the Titan's exhaust plume if they ejected in-flight and later added, "The best thing about Gemini was that they never had to make an escape.

[40] In a 1997 oral history, astronaut Thomas P. Stafford commented on the Gemini 6 launch abort in December 1965, when he and command pilot Wally Schirra nearly ejected from the spacecraft: So it turns out what we would have seen, had we had to do that, would have been two Roman candles going out, because we were 15 or 16 psi, pure oxygen, soaking in that for an hour and a half.

[42][43][44][45] The Apollo spacecraft was first conceived in 1960 as a three-man craft to follow Project Mercury, to accomplish several types of mission: ferrying astronauts to an Earth-orbiting space station, circumlunar flight, or a Moon landing.

The hypergolic propellant service propulsion engine was sized at 20,500 pounds-force (91,000 N) to lift the CSM off the lunar surface and send it back to Earth using a direct ascent mission profile.

This reduced the net spacecraft mass, allowing the mission to be launched with a single Saturn V. Since significant development work had started on the design, it was decided to continue with the existing design as Block I, while a Block II version capable of rendezvous with the LEM would be developed in parallel.

The Mercury-Gemini practice of using a prelaunch atmosphere of 16.7 pounds per square inch (1,150 mbar) pure oxygen proved to be disastrous in combination with the plug-door hatch design.

The crewed flight program was delayed while design changes were made to the Block II spacecraft to replace the pure oxygen pre-launch atmosphere with an air-like nitrogen/oxygen mixture, eliminate combustible materials from the cabin and the astronauts' space suits, and seal all electrical wiring and corrosive coolant lines.

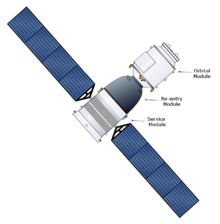

He employed a small, lightweight bell-shaped reentry capsule, with an orbital crew module attached to its nose, containing the bulk of the mission living space.

The service module would use two panels of electric solar cells for power generation, and contained a propulsion system engine.

Although originally envisaged as a development of SpaceX's uncrewed Dragon capsule which was used for the NASA Commercial Resupply Services contract, the demands of crewed spaceflight resulted in a significantly redesigned vehicle with limited commonality.

In fact, SpaceX has flown the same Dragon capsule to the International Space Station multiple times, with the first successful reuse occurring in June 2017.