Spanish heraldry

The tradition and art of heraldry first appeared in Spain at about the beginning of the eleventh century AD and its origin was similar to other European countries: the need for knights and nobles to distinguish themselves from one another on the battlefield, in jousts and in tournaments.

Knights wore armor from head to toe and were often in leadership positions, so it was essential to be able to identify them on the battlefield.

The order of display was: The Spanish nobility, unlike their other European counterparts, was based almost entirely on military service.

Indeed, the patents of nobility of many Spanish families contained bequeathals to illegitimate branches in case no legitimate heirs were found.

The Iberian heraldry also allows words and letters on the shield itself, a practice which is considered incorrect in northern Europe.

While crests are common in Portugal, they are more rare in Spain, with the helmets of Spanish coats of arms being instead usually topped by feathers.

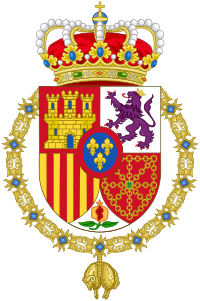

They can include, in addition to the shield, a helmet, mantling (cloth cape), wreath (a circle of silk with gold and silver cord twisted around and placed to cover the joint between the helmet and crest), the crest, the motto, chapeau, supporters (animals real or fictitious or people holding up the shield), the compartment (what the supporters are standing on), standards and Ensigns (personal flags), Coronets of rank, insignia of orders of chivalry and badges.

Military heraldic coronets[1] The Chronicler King of Arms in the Kingdoms of Spain was a civil servant who had the authority to grant armorial bearings.

Eventually, the task of settling these disputes was passed on to officials called heralds who were originally responsible for setting up tournaments and carrying messages from one noble to another.

Various chroniclers of arms were named for Spain, Castile, León, Frechas, Seville, Córdoba, Murcia, Granada (created in 1496), Estella, Viana, Navarre, Catalonia, Sicily, Aragon, Naples, Toledo, Valencia and Majorca.

While these appointments were not hereditary, at least fifteen Spanish families produced more than one herald each in the past five hundred years (compared to about the same number for England, Scotland and Ireland collectively).

The corps were considered part of the royal household and was generally responsible to the Master of the King's stable (an important position in the Middle Ages).

Many cities also have civic coats of arms; some are recent grants, others date back to the medieval period.

The Dukes of Alba, historically among the most powerful noble families in Europe, bear an elaborate achievement of arms, featuring the 'arms of justice' symbolising their hereditary office as Constables of Navarre.

Spain originally had a corporation of heralds (Spanish 'cronistas de armas') linked with the royal palace.