Spherical lune

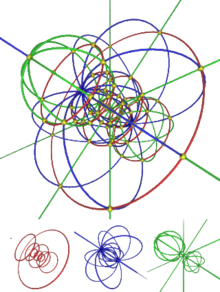

Common examples of great circles are lines of longitude (meridians) on a sphere, which meet at the north and south poles.

The surface area of a spherical lune is 2θ R2, where R is the radius of the sphere and θ is the dihedral angle in radians between the two half great circles.

When this angle equals 2π radians (360°) — i.e., when the second half great circle has moved a full circle, and the lune in between covers the sphere as a spherical monogon — the area formula for the spherical lune gives 4πR2, the surface area of the sphere.

For example, a regular hosotope {2,p,q} has digon faces, {2}2π/p,2π/q, where its vertex figure is a spherical platonic solid, {p,q}.

Or more specifically, the regular hosotope {2,4,3}, has 2 vertices, 8 180° arc edges in a cube, {4,3}, vertex figure between the two vertices, 12 lune faces, {2}π/4,π/3, between pairs of adjacent edges, and 6 hosohedral cells, {2,p}π/3.