Spinosaurus

'spine lizard') is a genus of spinosaurid dinosaur that lived in what now is North Africa during the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous period, about 100 to 94 million years ago.

Its long and narrow tail was deepened by tall, thin neural spines and elongated chevrons, forming a flexible fin or paddle-like structure.

It lived in a humid environment of tidal flats and mangrove forests alongside many other dinosaurs, as well as fish, crocodylomorphs, lizards, turtles, pterosaurs, and plesiosaurs.

[8][6] It was destroyed in World War II, specifically "during the night of 24/25 April 1944 in a British bombing raid of Munich" that severely damaged the building housing the Paläontologisches Museum München (Bavarian State Collection of Paleontology).

[6] In 2003, Oliver Rauhut suggested that Stromer's Spinosaurus holotype was a chimera, composed of vertebrae and neural spines from a carcharodontosaurid similar to Acrocanthosaurus and a dentary from Baryonyx or Suchomimus.

[2] Although it was originally ascribed to S. maroccanus, based on their examination of this cranial material, the 2016 study considered the difference between the two species to be not taxonomically significant and either ontogenetic or intraspecific, and thus tentatively assigned the specimen to S.

[19] This conclusion was further supported in 2018 by Arden and colleagues, who consider Sigilmassasaurus to be a distinct genus, though a very close relative of Spinosaurus, the two unified in the tribe Spinosaurini, coined in the study.

In 2021, Lacerda, Grillo and Romano noted that the anteromedial processes of the holotype maxillae (MN 6117-V) contact medially, a condition not observed in MSNM V4047 which has been referred to as a specimen of Spinosaurus, and thus adding a new possible diagnostic feature of Oxalaia.

[42] In 2023, Isasmendi and colleagues considered Oxalaia as a valid taxon based on the examination of its referred maxilla (MN 6119-V) which suggests that the position of its external naris would have been more anteriorly located, a condition similar to that of Irritator and baryonychines, differing from African spinosaurines including Spinosaurus aegyptiacus.

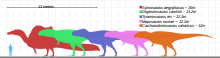

[44] Both Friedrich von Huene in 1926[45] and Donald F. Glut in 1982 listed it as among the most massive theropods in their surveys, at 15 m (49 ft) in length and upwards of 6 t (6.6 short tons) in weight.

"[51] They argued that the 2D graphical reconstruction of the aquatic hypothesis by Ibrahim and his colleagues in 2020[22] overestimated the presacral column length by 10%, ribcage depth by 25%, and forelimb length by 30% over dimensions based on CT-scanned fossils; these proportional overestimates shift the center of mass anteriorly when translated to a flesh model, and thus the estimate from Ibrahim and his colleagues cannot be considered a reliable body size estimate.

[54] The structure may also have been more hump-like than sail-like, as noted by Stromer in 1915 ("one might rather think of the existence of a large hump of fat [German: Fettbuckel], to which the [neural spines] gave internal support")[8] and by Jack Bowman Bailey in 1997.

[54][56] In 2014, Ibrahim and colleagues instead posited that the spines were covered tightly by skin, similar to a crested chameleon, given their compactness, sharp edges, and likely poor blood flow.

[14][11] An analysis of Spinosauridae by Arden and colleagues (2018) named the clade Spinosaurini and defined it as all spinosaurids closer to Spinosaurus aegyptiacus than to Irritator challengeri or Oxalaia quilombensis; it also found Siamosaurus suteethorni and Icthyovenator laosensis to be members of Spinosaurinae.

Examinations by Marcos Sales, Cesar Schultz, and colleagues (2017) indicate that the South American spinosaurids Angaturama, Irritator, and Oxalaia were intermediate between Baronychinae and Spinosaurinae based on their craniodental features and cladistic analysis.

Large animals, due to the relatively small ratio of surface area of their body compared to the overall volume (Haldane's principle), face far greater problems of dissipating excess heat at higher temperatures than gaining it at lower.

Bailey proposed instead that Spinosaurus and other dinosaurs with long neural spines had fatty humps on their backs for energy storage, insulation, and shielding from heat.

They therefore argue that Spinosaurus used its dorsal neural sail in the same manner as sailfish, and that it also employed its long narrow tail to stun prey like a modern thresher shark.

[59] Spinosaurus anatomy exhibits another feature that may have a modern analogy: its long tail resembled that of the thresher shark, employed to slap the water to herd and stun shoals of fish before devouring them (Oliver and colleagues, 2013).

When they slash or wipe their bills through shoaling fish by turning their heads, their dorsal sail and fins are outstretched to stabilize their bodies hydrodynamically (Lauder & Drucker, 2004).

Baryonyx was found with fish scales and bones from juvenile Iguanodon in its stomach, while a tooth embedded in a South American pterosaur bone suggests that spinosaurs occasionally preyed on pterosaurs,[61] but Spinosaurus was likely to have been a generalized and opportunistic predator, possibly a Cretaceous equivalent of large grizzly bears, being biased toward fishing, though it undoubtedly scavenged and took many kinds of small or medium-sized prey.

[62] A 2013 study by Andrew R. Cuff and Emily J. Rayfield concluded that bio-mechanical data suggests that Spinosaurus was not an obligate piscivore and that its diet was more closely associated with each individual's size.

[64] A 2024 paper suggests that Spinosaurus and other spinosaurines in addition to fish also preyed upon small to medium-sized terrestrial vertebrates, and had relatively weak bite forces compared to those of other theropods.

The elongated neural spines and chevrons, which run to the end of the tail on both dorsal and ventral sides, indicate that Spinosaurus was able to swim in a similar manner to modern crocodilians.

[57] David Hone and Thomas Holtz published a paper in 2021 in which they argue that the anatomy of Spinosaurus is more consistent with a shoreline generalist lifestyle rather than an active aquatic pursuit predator as suggested by Ibrahim.

Additionally, they argue that the general body shape of Spinosaurus is poorly adapted for this lifestyle, drawing on the amount of water drag and aquatic instability[67] from the sail, as well as the rigid trunk and seemingly scarcely-muscled tail.

Animals like crocodilians require a flexible body in order to move through the water and make sharp turns when chasing prey, and this is directly contradicted by Hone and Holtz's findings.

The paper found that the hind limbs of Spinosaurus were much shorter than previously believed, and that its center of mass was located in the midpoint of the torso region, as opposed to near the hip as in typical bipedal theropods.

[24] Paleontologist John Hutchinson of the Royal Veterinary College of the University of London has expressed skepticism to the new reconstruction, and cautioned that using different specimens can result in inaccurate chimaeras.

[92] The film's consulting paleontologist John R. Horner was quoted as saying, "If we base the ferocious factor on the length of the animal, there was nothing that ever lived on this planet that could match this creature [Spinosaurus].