Stalinism

Stalin's regime forcibly purged society of what it saw as threats to itself and its brand of communism (so-called "enemies of the people"), which included political dissidents, non-Soviet nationalists, the bourgeoisie, better-off peasants ("kulaks"),[9] and those of the working class who demonstrated "counter-revolutionary" sympathies.

After a political struggle that culminated in the defeat of the Bukharinists (the "Party's Right Tendency"), Stalinism was free to shape policy without opposition, ushering in an era of harsh totalitarianism that worked toward rapid industrialization regardless of the human cost.

Despite this, by the autumn of 1924, Stalin's notion of socialism in Soviet Russia was initially considered next to blasphemy by other Politburo members, including Zinoviev and Kamenev to the intellectual left; Rykov, Bukharin, and Tomsky to the pragmatic right; and the powerful Trotsky, who belonged to no side but his own.

[37] Other leftists, such as anarcho-communists, have criticized the party-state of the Stalin-era Soviet Union, accusing it of being bureaucratic and calling it a reformist social democracy rather than a form of revolutionary communism.

[45] A policy of ideological repression impacted various disciplinary fields such as genetics,[46] cybernetics,[47] biology,[48] linguistics,[49][50] physics,[51] sociology,[52] psychology,[53] pedology,[54] mathematical logic,[55] economics[56] and statistics.

Retrospectively, Lenin's primary associates such as Zinoviev, Trotsky, Radek and Bukharin were presented as "vacillating", "opportunists" and "foreign spies" whereas Stalin was depicted as the chief discipline during the revolution.

[67] In his book, The Stalin School of Falsification, Leon Trotsky argued that the Stalinist faction routinely distorted political events, forged a theoretical basis for irreconcilable concepts such as the notion of "Socialism in One Country" and misrepresented the views of opponents through an array of employed historians alongside economists to justify policy manoeuvering and safeguarding its own set of material interests.

[100] Many alleged anti-Soviet pretexts were used to brand individuals as "enemies of the people", starting the cycle of public persecution, often proceeding to interrogation, torture, and deportation, if not death.

Victims of such plots included Trotsky, Yevhen Konovalets, Ignace Poretsky, Rudolf Klement, Alexander Kutepov, Evgeny Miller, and the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) leadership in Catalonia (e.g., Andréu Nin Pérez).

[142][143][144] In February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev condemned the deportations as a violation of Leninism and reversed most of them, although it was not until 1991 that the Tatars, Meskhetians, and Volga Germans were allowed to return en masse to their homelands.

[145] Trotsky maintained that the disproportions and imbalances which became characteristic of Stalinist planning in the 1930s such as the underdeveloped consumer base along with the priority focus on heavy industry were due to a number of avoidable problems.

[146] Fredric Jameson has said that "Stalinism was…a success and fulfilled its historic mission, socially as well as economically" given that it "modernized the Soviet Union, transforming a peasant society into an industrial state with a literate population and a remarkable scientific superstructure.

After researching the biographies in the Soviet archives, he came to the same conclusion as Radzinsky and Kotkin (that Lenin had built a culture of violent autocratic totalitarianism of which Stalinism was a logical extension).

"[173] Similarly, historian Moshe Lewin writes, "The Soviet regime underwent a long period of 'Stalinism,' which in its basic features was diametrically opposed to the recommendations of [Lenin's] testament".

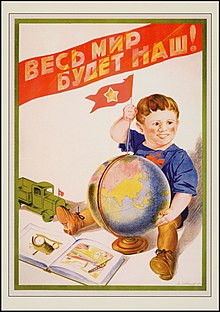

[181] Historian Robert Vincent Daniels also views the Stalinist period as a counterrevolution in Soviet cultural life that revived patriotic propaganda, the Tsarist programme of Russification and traditional, military ranks that Lenin had criticized as expressions of "Great Russian chauvinism".

Khrushchev contrasted this with Stalin's "despotism", which required absolute submission to his position, and highlighted that many of the people later annihilated as "enemies of the party ... had worked with Lenin during his life".

[184] In his memoirs, Khrushchev argued that his widespread purges of the "most advanced nucleus of people" among the Old Bolsheviks and leading figures in the military and scientific fields had "undoubtedly" weakened the nation.

[187] George Novack stressed the Bolsheviks' initial efforts to form a government with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries and bring other parties such as the Mensheviks into political legality.

They cited the outdated voter rolls, which did not acknowledge the split among the Socialist Revolutionary party, and the assembly's conflict with the Congress of the Soviets as an alternative democratic structure.

[189] A similar analysis is present in more recent works, such as those of Graeme Gill, who argues that Stalinism was "not a natural flow-on of earlier developments; [it formed a] sharp break resulting from conscious decisions by leading political actors.

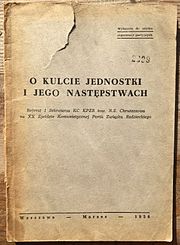

"[208] But after Stalin died in 1953, Khrushchev repudiated his policies and condemned his cult of personality in his Secret Speech to the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956, instituting de-Stalinization and relative liberalization, within the same political framework.

[209] Taking the side of the Chinese Communist Party in the Sino-Soviet split, the People's Socialist Republic of Albania remained committed, at least theoretically, to its brand of Stalinism (Hoxhaism) for decades under the leadership of Enver Hoxha.

[213] Trotsky also opposed the policy of forced collectivisation under Stalin and favoured a voluntary, gradual approach towards agricultural production[214][215] with greater tolerance for the rights of Soviet Ukrainians.

[219] Similarly, American Trotskyist David North drew attention to the fact that the generation of bureaucrats that rose to power under Stalin's tutelage presided over the Soviet Union's stagnation and breakdown.

Placing Stalinism in an international context, he argues that many forms of state interventionism the Stalinist government used, including social cataloguing, surveillance and concentration camps, predate the Soviet regime and originated outside of Russia.

He further argues that technologies of social intervention developed in conjunction with the work of 19th-century European reformers and greatly expanded during World War I, when state actors in all the combatant countries dramatically increased efforts to mobilize and control their populations.

[235] According to a 2015 Levada Center poll, 34% of respondents (up from 28% in 2007) say that leading the Soviet people to victory in World War II was such an outstanding achievement that it outweighed Stalin's mistakes.

[236] A 2019 Levada Center poll showed that support for Stalin, whom many Russians saw as the victor in the Great Patriotic War,[237] reached a record high in the post-Soviet era, with 51% regarding him as a positive figure and 70% saying his reign was good for the country.

[238] Lev Gudkov, a sociologist at the Levada Center, said, "Vladimir Putin's Russia of 2012 needs symbols of authority and national strength, however controversial they may be, to validate the newly authoritarian political order.

Stalin, a despotic leader responsible for mass bloodshed but also still identified with wartime victory and national unity, fits this need for symbols that reinforce the current political ideology.