Stall (fluid dynamics)

In fluid dynamics, a stall is a reduction in the lift coefficient generated by a foil as angle of attack exceeds its critical value.

[1] The critical angle of attack is typically about 15°, but it may vary significantly depending on the fluid, foil – including its shape, size, and finish – and Reynolds number.

A stall is a condition in aerodynamics and aviation such that if the angle of attack on an aircraft increases beyond a certain point, then lift begins to decrease.

Piston-engined and early jet transports had very good stall behaviour with pre-stall buffet warning and, if ignored, a straight nose-drop for a natural recovery.

Leading-edge developments on high-lift wings, and the introduction of rear-mounted engines and high-set tailplanes on the next generation of jet transports, also introduced unacceptable stall behaviour.

[9][10] The graph shows that the greatest amount of lift is produced as the critical angle of attack is reached (which in early-20th century aviation was called the "burble point").

Because aircraft models are normally used, rather than full-size machines, special care is needed to make sure that data is taken in the same Reynolds number regime (or scale speed) as in free flight.

For this reason wind tunnel results carried out at lower speeds and on smaller scale models of the real life counterparts often tend to overestimate the aerodynamic stall angle of attack.

Recovery from the stall involves lowering the aircraft nose, to decrease the angle of attack and increase the air speed, until smooth air-flow over the wing is restored.

The most common stall-spin scenarios occur on takeoff (departure stall) and during landing (base to final turn) because of insufficient airspeed during these maneuvers.

Attempting to increase the angle of attack at 1g by moving the control column back normally causes the aircraft to climb.

In these cases, the wings are already operating at a higher angle of attack to create the necessary force (derived from lift) to accelerate in the desired direction.

Increasing the g-loading still further, by pulling back on the controls, can cause the stalling angle to be exceeded, even though the aircraft is flying at a high speed.

For example, the Short Belfast heavy freighter had a marginal nose drop which was acceptable to the Royal Air Force.

The actual stall speed will vary depending on the airplane's weight, altitude, configuration, and vertical and lateral acceleration.

However, if the aircraft is turning or pulling up from a dive, additional lift is required to provide the vertical or lateral acceleration, and so the stall speed is higher.

Dynamic stall is a non-linear unsteady aerodynamic effect that occurs when airfoils rapidly change the angle of attack.

The rapid change can cause a strong vortex to be shed from the leading edge of the aerofoil, and travel backwards above the wing.

[40] Dynamic stall is an effect most associated with helicopters and flapping wings, though also occurs in wind turbines,[41] and due to gusting airflow.

[45] T-tail propeller aircraft are generally resistant to deep stalls, because the prop wash increases airflow over the wing root,[46] but may be fitted with a precautionary vertical tail booster during flight testing, as happened with the A400M.

Typical values both for the range of deep stall, as defined above, and the locked-in trim point are given for the Douglas DC-9 Series 10 by Schaufele.

The final design had no locked-in trim point, so recovery from the deep stall region was possible, as required to meet certification rules.

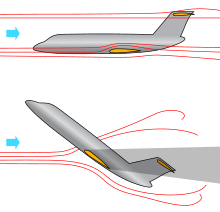

[50] Sketches showing how the wing wake blankets the tail may be misleading if they imply that deep stall requires a high body angle.

Nevertheless, the problem continues to cause accidents; on 3 June 1966, a Hawker Siddeley Trident (G-ARPY), was lost to deep stall;[57] deep stall is suspected to be cause of another Trident (the British European Airways Flight 548 G-ARPI) crash – known as the "Staines Disaster" – on 18 June 1972, when the crew failed to notice the conditions and had disabled the stall-recovery system.

[58] On 3 April 1980, a prototype of the Canadair Challenger business jet crashed after initially entering a deep stall from 17,000 ft and having both engines flame-out.

[60] It has been reported that a Boeing 727 entered a deep stall in a flight test, but the pilot was able to rock the airplane to increasingly higher bank angles until the nose finally fell through and normal control response was recovered.

Early speculation on reasons for the crash of Air France Flight 447 blamed an unrecoverable deep stall, since it descended in an almost flat attitude (15°) at an angle of attack of 35° or more.

Therefore, when the aircraft pitch increases abnormally, the canard will usually stall first, causing the nose to drop and so preventing the wing from reaching its critical AOA.

As a wing stalls, aileron effectiveness is reduced, rendering the plane difficult to control and increasing the risk of a spin.

Awareness of Lilienthal's accident and Wilbur's experience motivated the Wright Brothers to design their plane in "canard" configuration.