Stereotypes of African Americans

Stereotypes of African Americans are misleading beliefs about the culture of people with partial or total ancestry from any black racial groups of Africa whose ancestors resided in the United States since before 1865.

The Mammy archetype depicts a motherly black woman who is dedicated to her role working for a white family, a stereotype which dates back to the origin of Southern plantations.

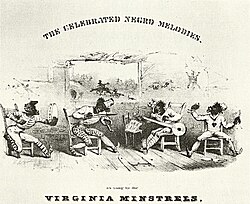

[14] Minstrel shows became a popular form of theater during the nineteenth century, which portrayed African Americans in stereotypical and often disparaging ways, some of the most common being that they are ignorant, lazy, buffoonish, superstitious, joyous, and musical.

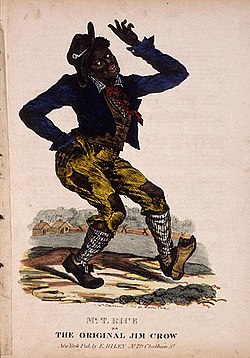

[1] One of the most popular styles of minstrelsy was Blackface, where White performers used burnt cork and later greasepaint, or applied shoe polish to their skin to blacken it, also exaggerating their lips, and often wearing woolly wigs, gloves, tailcoats, or ragged clothes to give a mocking, racially prejudicial theatrical portrayal of African Americans.

[16] The best-known stock character is Jim Crow, among several others, featured in innumerable stories, minstrel shows, and early films with racially prejudicial portrayals and messaging about African Americans.

The figure of the Golliwog, with black skin, white-rimmed eyes, exaggerated red lips, frizzy hair, high white collar, bow tie, and colourful jacket and pants, was based on the blackface minstrel tradition.

[19] The derived Commonwealth English epithet "wog" is applied more often to people from Sub-Saharan Africa and the Indian subcontinent than to African-Americans, but "Golly dolls" still in production mostly retain the look of the stereotypical blackface minstrel.

The Mammy archetype describes African-American women household slaves who served as nannies giving maternal care to the white children of the family, who received an unusual degree of trust and affection from their enslavers.

[24] The supposedly inherent physical strength, agility, and breeding abilities of Black men were lauded by white enslavers and auctioneers in order to promote the slaves they sold.

[14] Since then, the Mandingo stereotype has been used to socially and legally justify spinning instances of interracial affairs between Black men and White women into tales of uncontrollable and largely one-sided lust (from either party).

The novel was part of a larger series which presented, in graphic and erotic detail, various instances of interracial lust, promiscuity, nymphomania, and other sexual acts on a fictional slave-breeding plantation.

[27][28] During the era of slavery, white slave owners inflated the image of an enslaved Black woman raising her voice at her male counterparts, which was often necessary in day-to-day work.

White slave owners exercised control over enslaved Black women's sexuality and fertility, as their worth on the auction block was determined by their childbearing ability, ie.

[38] In the post-Reconstruction United States, 'black buck' was a racial slur used to describe black men who refused to bend to the law of white authority and were seen as irredeemably violent, rude, and lecherous.

Paintings like John Singleton Copley's Watson and the Shark (1778) and Samuel Jennings's Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences (1792) are early examples of the debate under way at that time as to the role of black people in America.

Nevertheless, Jennings' painting represents African Americans in a stereotypical role as passive, submissive beneficiaries of not only slavery's abolition but also knowledge, which liberty had graciously bestowed upon them.

The violinist in the 1813 painting, with his tattered and patched clothing, along with a bottle protruding from his coat pocket, appears to be an early model for Rice's Jim Crow character.

[47] In the 1980s and the 1990s, stereotypes of black men shifted and the primary and common images were of drug dealers, crack victims, the underclass and impoverished, the homeless, and subway muggers.

[4] Similarly, Douglas (1995), who looked at O. J. Simpson, Louis Farrakhan, and the Million Man March, found that the media placed African-American men on a spectrum of good versus evil.

Race and folklore professor Claire Schmidt attributes the latter both to its popularity in Southern cuisine and to a scene from the film Birth of a Nation in which a rowdy African-American man is seen eating fried chicken in a legislative hall.

[59] Contemporary women of the African Diaspora’s engagement in this performance of physiological and emotional strength stems from a history of degradation evident during the TransAtlantic Middle Passage, the institution of U.S. Slavery, and the era of racial caste imposed by Jim Crow during the 19th-20th century.

[60] In addition to igniting discourse on respectability politics, the ‘Strong Black Woman’ stereotype also functions as a coping mechanism whereby “strength” manifests as heightened independence, self-sacrificial habits, resilience, and reluctance to express vulnerability.

However, prolonged adherence to the ‘Strong Black Woman’ persona induces increased psychological distress in the forms of “depression, stress, anxiety, and suicidal behavior”.

The BAP figure is often critiqued as a product of post-segregation Black wealth, where women who gained access to educational and social institutions are seen as having a sense of entitlement and detachment from their racial identity.

[76] African-American women have been represented in film and television in a variety of different ways, starting from the stereotype/archetype of "mammy" (as is exemplified the role played by Hattie McDaniel in Gone with the Wind) drawn from minstrel shows,[77] through to the heroines of blaxploitation movies of the 1970s, but the latter was then weakened by commercial studios.

[83] In another example, a study of the portrayal of race, ethnicity, and nationality in televised sporting events by the journalist Derrick Z. Jackson in 1989 showed that black people were more likely than whites to be described in demeaning intellectual terms.

[84] According to Lawrence Grossman, former president of CBS News and PBS, television newscasts "disproportionately show African Americans under arrest, living in slums, on welfare, and in need of help from the community.

Media's reliance on stereotypes of women and African Americans not only hindered civil rights but also helped determine how people treated marginalized groups, her study found.

Exposure to violent, misogynistic rap music performed by African American male rappers has been shown to activate negative stereotypes towards black men as hostile, criminal and sexist.

In a survey study, adolescent African American women watching rap videos and perceiving them to contain more sexual stereotypes were more likely to binge drink, test positive for marijuana and have a negative body image.