String theory

In some cases, by modeling spacetime in a different number of dimensions, a theory becomes more mathematically tractable, and one can perform calculations and gain general insights more easily.

This idea plays an important role in attempts to develop models of real-world physics based on string theory, and it provides a natural explanation for the weakness of gravity compared to the other fundamental forces.

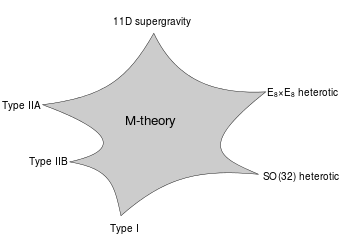

Witten's conjecture was based on the work of a number of other physicists, including Ashoke Sen, Chris Hull, Paul Townsend, and Michael Duff.

Shortly after this discovery, Michael Duff, Paul Howe, Takeo Inami, and Kellogg Stelle considered a particular compactification of eleven-dimensional supergravity with one of the dimensions curled up into a circle.

[48] The development of the matrix model formulation of M-theory has led physicists to consider various connections between string theory and a branch of mathematics called noncommutative geometry.

In the 1970s, the physicist Jacob Bekenstein suggested that the entropy of a black hole is instead proportional to the surface area of its event horizon, the boundary beyond which matter and radiation may escape its gravitational attraction.

[60] Subsequent work by Strominger, Vafa, and others refined the original calculations and gave the precise values of the "quantum corrections" needed to describe very small black holes.

More precisely, Hawking's calculation seemed to conflict with one of the basic postulates of quantum mechanics, which states that physical systems evolve in time according to the Schrödinger equation.

Such collisions cause the quarks that make up atomic nuclei to deconfine at temperatures of approximately two trillion kelvin, conditions similar to those present at around 10−11 seconds after the Big Bang.

[c] In an article appearing in 2005, Đàm Thanh Sơn and his collaborators showed that the AdS/CFT correspondence could be used to understand some aspects of the quark-gluon plasma by describing it in the language of string theory.

Some condensed matter theorists including Subir Sachdev hope that the AdS/CFT correspondence will make it possible to describe these systems in the language of string theory and learn more about their behavior.

For example, the atoms slow to a halt at a rate that depends on the temperature and on the Planck constant, the fundamental parameter of quantum mechanics, which does not enter into the description of the other phases.

Despite its success in explaining many observed features of the universe including galactic redshifts, the relative abundance of light elements such as hydrogen and helium, and the existence of a cosmic microwave background, there are several questions that remain unanswered.

While these approaches might eventually find support in observational data such as measurements of the cosmic microwave background, the application of string theory to cosmology is still in its early stages.

[110][111] Borcherds' work used ideas from string theory in an essential way, extending earlier results of Igor Frenkel, James Lepowsky, and Arne Meurman, who had realized the monster group as the symmetries of a particular[which?]

In the 1960s, Geoffrey Chew and Steven Frautschi discovered that the mesons make families called Regge trajectories with masses related to spins in a way that was later understood by Yoichiro Nambu, Holger Bech Nielsen and Leonard Susskind to be the relationship expected from rotating strings.

By manipulating combinations of gamma functions, Veneziano was able to find a consistent scattering amplitude with poles on straight lines, with mostly positive residues, which obeyed duality and had the appropriate Regge scaling at high energy.

Miguel Virasoro and Joel Shapiro found a different amplitude now understood to be that of closed strings, while Ziro Koba and Holger Nielsen generalized Veneziano's integral representation to multiparticle scattering.

Veneziano and Sergio Fubini introduced an operator formalism for computing the scattering amplitudes that was a forerunner of world-sheet conformal theory, while Virasoro understood how to remove the poles with wrong-sign residues using a constraint on the states.

The scattering amplitudes were derived systematically from the action principle by Peter Goddard, Jeffrey Goldstone, Claudio Rebbi, and Charles Thorn, giving a space-time picture to the vertex operators introduced by Veneziano and Fubini and a geometrical interpretation to the Virasoro conditions.

Stanley Mandelstam formulated a world sheet conformal theory for both the bose and fermi case, giving a two-dimensional field theoretic path-integral to generate the operator formalism.

At the same time, quantum chromodynamics was recognized as the correct theory of hadrons, shifting the attention of physicists and apparently leaving the bootstrap program in the dustbin of history.

Philip Candelas, Gary Horowitz, Andrew Strominger and Edward Witten found that the Calabi–Yau manifolds are the compactifications that preserve a realistic amount of supersymmetry, while Lance Dixon and others worked out the physical properties of orbifolds, distinctive geometrical singularities allowed in string theory.

[31] During this period, Tom Banks, Willy Fischler, Stephen Shenker and Leonard Susskind formulated matrix theory, a full holographic description of M-theory using IIA D0 branes.

Andrew Strominger and Cumrun Vafa calculated the entropy of certain configurations of D-branes and found agreement with the semi-classical answer for extreme charged black holes.

[citation needed] To construct models of particle physics based on string theory, physicists typically begin by specifying a shape for the extra dimensions of spacetime.

String theory as it is currently understood has an enormous number of vacuum states, typically estimated to be around 10500, and these might be sufficiently diverse to accommodate almost any phenomenon that might be observed at low energies.

He argues that the extreme popularity of string theory among theoretical physicists is partly a consequence of the financial structure of academia and the fierce competition for scarce resources.

[135] In his book The Road to Reality, mathematical physicist Roger Penrose expresses similar views, stating "The often frantic competitiveness that this ease of communication engenders leads to bandwagon effects, where researchers fear to be left behind if they do not join in.

"[136] Penrose also claims that the technical difficulty of modern physics forces young scientists to rely on the preferences of established researchers, rather than forging new paths of their own.