Subglacial lake

[3] Meltwater flows from regions of high to low hydraulic pressure under the ice and pools, creating a body of liquid water that can be isolated from the external environment for millions of years.

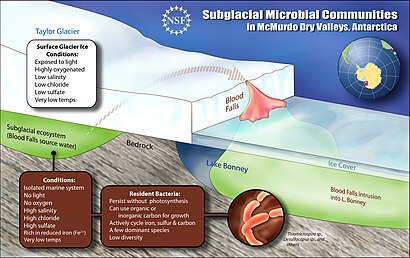

They contain active biological communities of extremophilic microbes that are adapted to cold, low-nutrient conditions and facilitate biogeochemical cycles independent of energy inputs from the sun.

In fact, theoretically a subglacial lake can even exist on the top of a hill, provided that the ice over it is thin enough to form the required hydrostatic seal.

[15] Russian revolutionary and scientist Peter A. Kropotkin first proposed the idea of liquid freshwater under the Antarctic Ice Sheet at the end of the 19th century.

In 1959 and 1964, during two of his four Soviet Antarctic Expeditions, Russian geographer and explorer Andrey P. Kapitsa used seismic sounding to prepare a profile of the layers of the geology below Vostok Station in Antarctica.

[18] Beginning in the late 1950s, English physicists Stan Evans and Gordon Robin began using the radioglaciology technique of radio-echo sounding (RES) to chart ice thickness.

In 2005, Laurence Gray and a team of glaciologists began to interpret surface ice slumping and raising from RADARSAT data, which indicated there could be hydrologically “active” subglacial lakes subject to water movement.

[25] Between 2003 and 2009, a survey of long-track measurements of ice-surface elevation using the ICESat satellite as a part of NASA's Earth Observing System produced the first continental-scale map of the active subglacial lakes in Antarctica.

[20] Following this meeting, SCAR drafted a code of conduct for ice drilling expeditions and in situ (on-site) measurements and sampling of subglacial lakes.

[43] The majority of Icelandic subglacial lakes are located beneath the Vatnajökull and Mýrdalsjökull ice caps, where melting from hydrothermal activity creates permanent depressions that fill with meltwater.

[44] Hydrothermal activity beneath the Mýrdalsjökull ice cap is thought to have created at least 12 small depressions within an area constrained by three major subglacial drainage basins.

[7] Many of these depressions are known to contain subglacial lakes that are subject to massive, catastrophic drainage events from volcanic eruptions, creating a significant hazard for nearby human populations.

Despite the cold temperatures, low nutrients, high pressure, and total darkness in subglacial lakes, these ecosystems have been found to harbor thousands of different microbial species and some signs of higher life.

No photosynthesis can occur in the darkness of subglacial lakes, so their food webs are instead driven by chemosynthesis and the consumption of ancient organic carbon deposited before glaciation.

[54] Despite their typically oligotrophic conditions, subglacial lakes and sediments are thought to contain regionally and globally significant amounts of nutrients, particularly carbon.

[60] Melting of the layer of glacial ice above the subglacial lake also supplies underlying waters with iron, nitrogen, and phosphorus-containing minerals, in addition to some dissolved organic carbon and bacterial cells.

[61] Oxic or slightly suboxic waters often reside near the glacier-lake interface, while anoxia dominates in the lake interior and sediments due to respiration by microbes.

[59] The products of sulfide oxidation can enhance the chemical weathering of carbonate and silicate minerals in subglacial sediments, particularly in lakes with long residence times.

[51] Subglacial sedimentary basins under the Antarctic Ice Sheet have accumulated an estimated ~21,000 petagrams of organic carbon, most of which comes from ancient marine sediments.

[57] In the event of ice sheet collapse, subglacial organic carbon could be more readily respired and thus released to the atmosphere and create a positive feedback on climate change.

[71] Methane has been detected in subglacial Lake Whillans,[72] and experiments have shown that methanogenic archaea can be active in sediments beneath both Antarctic and Arctic glaciers.

[9][61] Researching microbial diversity and adaptations in subglacial lakes is of particular interest to scientists studying astrobiology, as well as the history and limits of life on Earth.

[12][53] Despite the resources available to subglacial lake heterotrophs, these bacteria appear to be exceptionally slow-growing, potentially indicating that they dedicate most of their energy to survival rather than growth.

Other metabolisms used by subglacial lake microbes include methanogenesis, methanotrophy, and chemolithoheterotrophy, in which bacteria consume organic matter while oxidizing inorganic elements.

In subglacial Lake Whillans, the WISSARD expedition collected sediment cores and water samples, which contained 130,000 microbial cells per milliliter and 3,914 different bacterial species.

[36][79] In January 2019, the SALSA team collected sediment and water samples from subglacial Lake Mercer and found diatom shells and well-preserved carcasses from crustaceans and a tardigrade.

[89] A low-diversity microbial community has also been found in the east Skaftárketill and Kverkfjallalón subglacial lakes, where bacteria include Geobacter and Desulfuosporosinus species that can use sulfur and iron for anaerobic respiration.

Discoveries of living extremophilic microbes in Earth's subglacial lakes could suggest that life may persist in similar environments on extraterrestrial bodies.

[11][10] Subglacial lakes also provide study systems for planning research efforts in remote, logistically challenging locations that are sensitive to biological contamination.

[95][96] Satellite analysis of an icy water vapor plume escaping from fissures in Enceladus' surface reveals significant subsurface production of hydrogen, which may point towards the reduction of iron-bearing minerals and organic matter.