Speed of sound

The speed has a weak dependence on frequency and pressure in dry air, deviating slightly from ideal behavior.

Sir Isaac Newton's 1687 Principia includes a computation of the speed of sound in air as 979 feet per second (298 m/s).

[5] In 1709, the Reverend William Derham, Rector of Upminster, published a more accurate measure of the speed of sound, at 1,072 Parisian feet per second.

This is longer than the standard "international foot" in common use today, which was officially defined in 1959 as 304.8 mm, making the speed of sound at 20 °C (68 °F) 1,055 Parisian feet per second).

Derham used a telescope from the tower of the church of St. Laurence, Upminster to observe the flash of a distant shotgun being fired, and then measured the time until he heard the gunshot with a half-second pendulum.

Measurements were made of gunshots from a number of local landmarks, including North Ockendon church.

[6] The transmission of sound can be illustrated by using a model consisting of an array of spherical objects interconnected by springs.

Sound passes through the system by compressing and expanding the springs, transmitting the acoustic energy to neighboring spheres.

An illustrative example of the two effects is that sound travels only 4.3 times faster in water than air, despite enormous differences in compressibility of the two media.

The speed of sound in mathematical notation is conventionally represented by c, from the Latin celeritas meaning "swiftness".

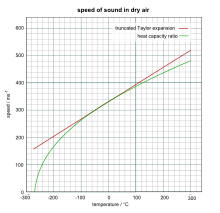

For a given ideal gas with constant heat capacity and composition, the speed of sound is dependent solely upon temperature; see § Details below.

[10] Newton famously considered the speed of sound before most of the development of thermodynamics and so incorrectly used isothermal calculations instead of adiabatic.

[9] Wind shear of 4 m/(s · km) can produce refraction equal to a typical temperature lapse rate of 7.5 °C/km.

For this reason, the concept of speed of sound (except for frequencies approaching zero) progressively loses its range of applicability at high altitudes.

The molecular composition of the gas contributes both as the mass (M) of the molecules, and their heat capacities, and so both have an influence on speed of sound.

This gives the 9% difference, and would be a typical ratio for speeds of sound at room temperature in helium vs. deuterium, each with a molecular weight of 4.

However, vibrational modes simply cause gammas which decrease toward 1, since vibration modes in a polyatomic gas give the gas additional ways to store heat which do not affect temperature, and thus do not affect molecular velocity and sound velocity.

The speed is proportional to the square root of the absolute temperature, giving an increase of about 0.6 m/s per degree Celsius.

Standard values of the speed of sound are quoted in the limit of low frequencies, where the wavelength is large compared to the mean free path.

Aircraft flight instruments, however, operate using pressure differential to compute Mach number, not temperature.

Aircraft flight instruments need to operate this way because the stagnation pressure sensed by a Pitot tube is dependent on altitude as well as speed.

The earliest reasonably accurate estimate of the speed of sound in air was made by William Derham and acknowledged by Isaac Newton.

On a calm day, a synchronized pocket watch would be given to an assistant who would fire a shotgun at a pre-determined time from a conspicuous point some miles away, across the countryside.

Lastly, by making many observations, using a range of different distances, the inaccuracy of the half-second pendulum could be averaged out, giving his final estimate of the speed of sound.

Modern stopwatches enable this method to be used today over distances as short as 200–400 metres, and not needing something as loud as a shotgun.

The simplest concept is the measurement made using two microphones and a fast recording device such as a digital storage scope.

A 2002 review[20] found that a 1963 measurement by Smith and Harlow using a cylindrical resonator gave "the most probable value of the standard speed of sound to date."

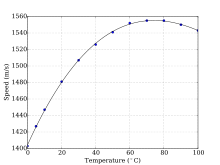

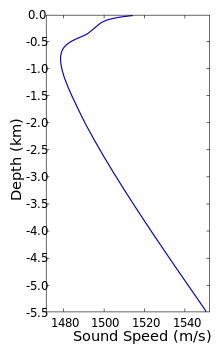

In salt water that is free of air bubbles or suspended sediment, sound travels at about 1500 m/s (1500.235 m/s at 1000 kilopascals, 10 °C and 3% salinity by one method).

[27] For more information see Dushaw et al.[28] An empirical equation for the speed of sound in sea water is provided by Mackenzie:[29]

[32] When sound spreads out evenly in all directions in three dimensions, the intensity drops in proportion to the inverse square of the distance.