Substitution model

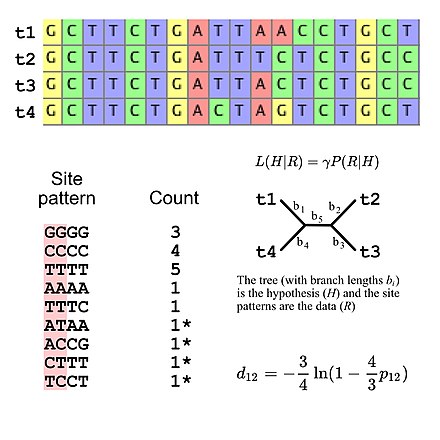

Substitution models are used to calculate the likelihood of phylogenetic trees using multiple sequence alignment data.

Substitution models are also central to phylogenetic invariants because they are necessary to predict site pattern frequencies given a tree topology.

Substitution models are also necessary to simulate sequence data for a group of organisms related by a specific tree.

Generalised time reversible (GTR) is the most general neutral, independent, finite-sites, time-reversible model possible.

Some publications write the nucleotides in a different order (e.g., some authors choose to group two purines together and the two pyrimidines together; see also models of DNA evolution).

The alternative notation also makes it easier to understand the sub-models of the GTR model, which simply correspond to cases where exchangeability and/or equilibrium base frequency parameters are constrained to take on equal values.

The alternative notation also makes it straightforward to see how the GTR model can be applied to biological alphabets with a larger state-space (e.g., amino acids or codons).

In this regard, the use of mixture models in phylogenentic frameworks is convenient to better mimic the molecular evolution observed in real data.

[18] Typically, a branch length of a phylogenetic tree is expressed as the expected number of substitutions per site; if the evolutionary model indicates that each site within an ancestral sequence will typically experience x substitutions by the time it evolves to a particular descendant's sequence then the ancestor and descendant are considered to be separated by branch length x.

A model is said to have a strict molecular clock if the expected number of substitutions per year μ is constant regardless of which species' evolution is being examined.

For example, even though rodents are genetically very similar to primates, they have undergone a much higher number of substitutions in the estimated time since divergence in some regions of the genome.

[21][22] When studying ancient events like the Cambrian explosion under a molecular clock assumption, poor concurrence between cladistic and phylogenetic data is often observed.

[23][24] Models that can take into account variability of the rate of the molecular clock between different evolutionary lineages in the phylogeny are called “relaxed” in opposition to “strict”.

In 1981, Joseph Felsenstein proposed a four-parameter model (F81[8]) in which the substitution rate corresponds to the equilibrium frequency of the target nucleotide.

An alternative way to analyze DNA sequence data is to recode the nucleotides as purines (R) and pyrimidines (Y);[30][31] this practice is often called RY-coding.

[32] Insertions and deletions in multiple sequence alignments can also be encoded as binary data[33] and analyzed in using a two-state model.

For many analyses, particularly for longer evolutionary distances, the evolution is modeled on the amino acid level.

However, several advantages speak in favor of using the amino acid information: DNA is much more inclined to show compositional bias than amino acids, not all positions in the DNA evolve at the same speed (non-synonymous mutations are less likely to become fixed in the population than synonymous ones), but probably most important, because of those fast evolving positions and the limited alphabet size (only four possible states), the DNA suffers from more back substitutions, making it difficult to accurately estimate evolutionary longer distances.

The earliest efforts used methods similar to those used by Dayhoff, using large-scale matching of the protein database to generate a new log-odds matrix[48] and the JTT (Jones-Taylor-Thornton) model.

The IQ-Tree software package allows users to infer their own time reversible model using QMaker,[54] or non-time-reversible using nQMaker.

Mechanistic models describe all substitutions as a function of a number of parameters which are estimated for every data set analyzed, preferably using maximum likelihood.

This has the advantage that the model can be adjusted to the particularities of a specific data set (e.g. different composition biases in DNA).

(using the one-letter IUPAC codes for amino acids to indicate their equilibrium frequencies) are often estimated from the data[50] while keeping the exchangeability matrix fixed.

The NCM model assumes all of the data (e.g., homologous nucleotides, amino acids, or morphological characters) are related by a common phylogenetic tree.

This means that substitution models can be viewed as implying a specific multinomial distribution for site pattern frequencies.

However, it is possible to specify the expected site pattern frequencies using five degrees of freedom if using the Jukes-Cantor model of DNA evolution,[7] which is a simple substitution model that allows one to calculate the expected site pattern frequencies only the tree topology and the branch lengths (given four taxa an unrooted bifurcating tree has five branch lengths).

Substitution models also make it possible to simulate sequence data using Monte Carlo methods.

This can be illustrated using a "toy" example: we can use a binary alphabet to score the following phenotypic traits "has feathers", "lays eggs", "has fur", "is warm-blooded", and "capable of powered flight".

There is an obvious similarity between use of molecular or phenotypic data in the field of cladistics and analyses of morphological characters using a substitution model.

The field of cladistics (defined in the strictest sense) favor the use of the maximum parsimony criterion for phylogenetic inference.