Supermassive black hole

Black holes are a class of astronomical objects that have undergone gravitational collapse, leaving behind spheroidal regions of space from which nothing can escape, including light.

[7][8] Accretion of interstellar gas onto supermassive black holes is the process responsible for powering active galactic nuclei (AGNs) and quasars.

[16] The Schwarzschild radius of the event horizon of a nonrotating and uncharged supermassive black hole of around 1 billion M☉ is comparable to the semi-major axis of the orbit of planet Uranus, which is about 19 AU.

Some studies have suggested that the maximum natural mass that a black hole can reach, while being luminous accretors (featuring an accretion disk), is typically on the order of about 50 billion M☉.

[26] In 1963, Fred Hoyle and W. A. Fowler proposed the existence of hydrogen-burning supermassive stars (SMS) as an explanation for the compact dimensions and high energy output of quasars.

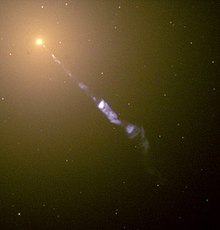

[29] Meanwhile, in 1967, Martin Ryle and Malcolm Longair suggested that nearly all sources of extra-galactic radio emission could be explained by a model in which particles are ejected from galaxies at relativistic velocities, meaning they are moving near the speed of light.

[30] Martin Ryle, Malcolm Longair, and Peter Scheuer then proposed in 1973 that the compact central nucleus could be the original energy source for these relativistic jets.

[33] Sagittarius A* was discovered and named on February 13 and 15, 1974, by astronomers Bruce Balick and Robert Brown using the Green Bank Interferometer of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

[35] Using the Very Long Baseline Array to observe Messier 106, Miyoshi et al. (1995) were able to demonstrate that the emission from an H2O maser in this galaxy came from a gaseous disk in the nucleus that orbited a concentrated mass of 3.6×107 M☉, which was constrained to a radius of 0.13 parsecs.

[36] Accompanying this observation which provided the first confirmation of supermassive black holes was the discovery[37] of the highly broadened, ionised iron Kα emission line (6.4 keV) from the galaxy MCG-6-30-15.

[2] In March 2020, astronomers suggested that additional subrings should form the photon ring, proposing a way of better detecting these signatures in the first black hole image.

[54] Large, high-redshift clouds of metal-free gas,[55] when irradiated by a sufficiently intense flux of Lyman–Werner photons,[56] can avoid cooling and fragmenting, thus collapsing as a single object due to self-gravitation.

Normally, the process of accretion involves transporting a large initial endowment of angular momentum outwards, and this appears to be the limiting factor in black hole growth.

The majority of the mass growth of supermassive black holes is thought to occur through episodes of rapid gas accretion, which are observable as active galactic nuclei or quasars.

[21] The so-called 'chaotic accretion' presumably has to involve multiple small-scale events, essentially random in time and orientation if it is not controlled by a large-scale potential in this way.

[21] All of these considerations suggested that SMBHs usually cross the critical theoretical mass limit at modest values of their spin parameters, so that 5×1010 M☉ in all but rare cases.

Dynamical friction on the hosted SMBH objects causes them to sink toward the center of the merged mass, eventually forming a pair with a separation of under a kiloparsec.

The interaction of this pair with surrounding stars and gas will then gradually bring the SMBH together as a gravitationally bound binary system with a separation of ten parsecs or less.

[75] The gravitational waves from this coalescence can give the resulting SMBH a velocity boost of up to several thousand km/s, propelling it away from the galactic center and possibly even ejecting it from the galaxy.

[70][18] Some of the best evidence for the presence of black holes is provided by the Doppler effect whereby light from nearby orbiting matter is red-shifted when receding and blue-shifted when advancing.

This effect has been allowed for in modern computer-generated images such as the example presented here, based on a plausible model[90] for the supermassive black hole in Sgr A* at the center of the Milky Way.

Direct Doppler measures of water masers surrounding the nuclei of nearby galaxies have revealed a very fast Keplerian motion, only possible with a high concentration of matter in the center.

The unusual event may have been caused by the breaking apart of an asteroid falling into the black hole or by the entanglement of magnetic field lines within gas flowing into Sagittarius A*, according to astronomers.

In these galaxies, the root mean square (or rms) velocities of the stars or gas rises proportionally to 1/r near the center, indicating a central point mass.

In all other galaxies observed to date, the rms velocities are flat, or even falling, toward the center, making it impossible to state with certainty that a supermassive black hole is present.

This rare event is assumed to be a relativistic outflow (material being emitted in a jet at a significant fraction of the speed of light) from a star tidally disrupted by the SMBH.

[105] The largest supermassive black hole in the Milky Way's vicinity appears to be that of Messier 87 (i.e., M87*), at a mass of (6.5±0.7)×109 (c. 6.5 billion) M☉ at a distance of 48.92 million light-years.

[115] In 2012, astronomers reported an unusually large mass of approximately 17 billion M☉ for the black hole in the compact, lenticular galaxy NGC 1277, which lies 220 million light-years away in the constellation Perseus.

The eruption released shock waves and jets of high-energy particles that punched the intracluster medium, creating a cavity about 1.5 million light-years wide – ten times the Milky Way's diameter.

[128][124][129][130] In February 2021, astronomers released, for the first time, a very high-resolution image of 25,000 active supermassive black holes, covering four percent of the Northern celestial hemisphere, based on ultra-low radio wavelengths, as detected by the Low-Frequency Array (LOFAR) in Europe.

From: Chandra X-ray Observatory