Supernova

[2][3] Compared to a star's entire history, the visual appearance of a supernova is very brief, sometimes spanning several months, so that the chances of observing one with the naked eye are roughly once in a lifetime.

[10] Johannes Kepler began observing SN 1604 at its peak on 17 October 1604, and continued to make estimates of its brightness until it faded from naked eye view a year later.

While most type II supernovae show very broad emission lines which indicate expansion velocities of many thousands of kilometres per second, some, such as SN 2005gl, have relatively narrow features in their spectra.

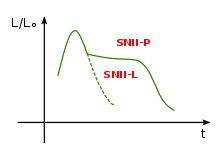

[65] Type II supernovae with normal spectra dominated by broad hydrogen lines that remain for the life of the decline are classified on the basis of their light curves.

The most common type shows a distinctive "plateau" in the light curve shortly after peak brightness where the visual luminosity stays relatively constant for several months before the decline resumes.

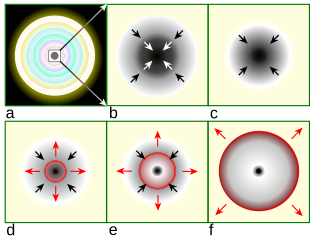

Some calibrations are required to compensate for the gradual change in properties or different frequencies of abnormal luminosity supernovae at high redshift, and for small variations in brightness identified by light curve shape or spectrum.

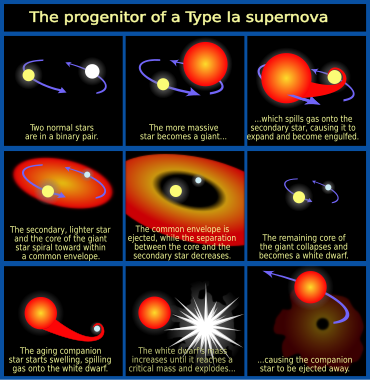

[83] Within a few seconds of the collapse process, a substantial fraction of the matter in the white dwarf undergoes nuclear fusion, releasing enough energy (1–2×1044 J)[85] to unbind the star in a supernova.

[91] A second model for the formation of type Ia supernovae involves the merger of two white dwarf stars, with the combined mass momentarily exceeding the Chandrasekhar limit.

[94] Abnormally bright type Ia supernovae occur when the white dwarf already has a mass higher than the Chandrasekhar limit,[95] possibly enhanced further by asymmetry,[96] but the ejected material will have less than normal kinetic energy.

The inner core eventually reaches typically 30 km in diameter[112] with a density comparable to that of an atomic nucleus, and neutron degeneracy pressure tries to halt the collapse.

A process that is not clearly understood[update] is necessary to allow the outer layers of the core to reabsorb around 1044 joules[114] (1 foe) from the neutrino pulse, producing the visible brightness, although there are other theories that could power the explosion.

This fallback will reduce the kinetic energy created and the mass of expelled radioactive material, but in some situations, it may also generate relativistic jets that result in a gamma-ray burst or an exceptionally luminous supernova.

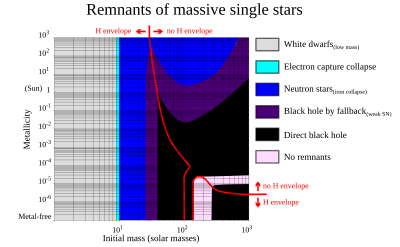

At moderate to high metallicity, stars near the upper end of that mass range will have lost most of their hydrogen when core collapse occurs and the result will be a type II-L supernova.

[135][136] In 2022 a team of astronomers led by researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science reported the first supernova explosion showing direct evidence for a Wolf-Rayet progenitor star.

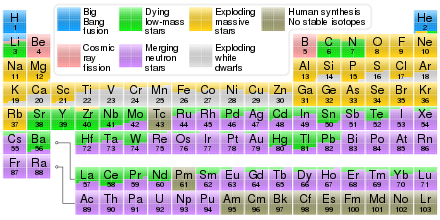

[148] Although the energy that initially powers each type of supernovae is delivered promptly, the light curves are dominated by subsequent radioactive heating of the rapidly expanding ejecta.

[150] It is now known by direct observation that much of the light curve (the graph of luminosity as a function of time) after the occurrence of a type II Supernova, such as SN 1987A, is explained by those predicted radioactive decays.

Later measurements by space gamma-ray telescopes of the small fraction of the 56Co and 57Co gamma rays that escaped the SN 1987A remnant without absorption confirmed earlier predictions that those two radioactive nuclei were the power sources.

[150] The late-time decay phase of visual light curves for different supernova types all depend on radioactive heating, but they vary in shape and amplitude because of the underlying mechanisms, the way that visible radiation is produced, the epoch of its observation, and the transparency of the ejected material.

The visual light output is dominated by kinetic energy rather than radioactive decay for several months, due primarily to the existence of hydrogen in the ejecta from the atmosphere of the supergiant progenitor star.

These light curves are produced by the highly efficient conversion of kinetic energy of the ejecta into electromagnetic radiation by interaction with the dense shell of material.

In some core collapse supernovae, fallback onto a black hole drives relativistic jets which may produce a brief energetic and directional burst of gamma rays and also transfers substantial further energy into the ejected material.

[180] When a supernova occurs inside a small dense cloud of circumstellar material, it will produce a shock wave that can efficiently convert a high fraction of the kinetic energy into electromagnetic radiation.

[186][187][188] Type Ib and Ic supernovae are hypothesised to have been produced by core collapse of massive stars that have lost their outer layer of hydrogen and helium, either via strong stellar winds or mass transfer to a companion.

One study has shown a possible route for low-luminosity post-red supergiant luminous blue variables to collapse, most likely as a type IIn supernova.

A small number would be from rapidly rotating massive stars, likely corresponding to the highly energetic type Ic-BL events that are associated with long-duration gamma-ray bursts.

[213][214] The kinetic energy of an expanding supernova remnant can trigger star formation by compressing nearby, dense molecular clouds in space.

Using the arrival of a neutrino signal may provide a trigger that can identify the time window in which to seek the gravitational wave, helping to distinguish the latter from background noise.

A greater temperature difference between the poles and the equator created stronger winds, increased ocean mixing, and resulted in the transport of nutrients to shallow waters along the continental shelves.

The closest-known candidate is IK Pegasi (HR 8210), about 150 light-years away,[232][233] but observations suggest it could be as long as 1.9 billion years before the white dwarf can accrete the critical mass required to become a type Ia supernova.

There is a smaller chance that the next core collapse supernova will be produced by a different type of massive star such as a yellow hypergiant, luminous blue variable, or Wolf–Rayet.