Supply-side economics

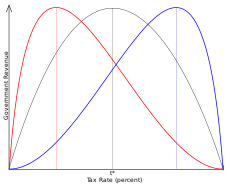

Such policies are of several general varieties: A basis of supply-side economics is the Laffer curve, a theoretical relationship between rates of taxation and government revenue.

[19][20] Bruce Bartlett, an advocate of supply-side economics, traced the school of thought's intellectual descent from the philosophers Ibn Khaldun and David Hume, satirist Jonathan Swift, political economist Adam Smith and United States Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton.

[23] On the other hand, supply-side economists argued that the alleged collective benefit (i.e. increased economic output and efficiency) provided the main impetus for tax cuts.

Wanniski advocated lower tax rates and a return to some kind of gold standard, similar to the 1944–1971 Bretton Woods System that Nixon abandoned.

James D. Gwartney and Richard L. Stroup provide a definition of supply-side economics as the belief that adjustments in marginal tax rates have significant effects on the total supply.

[28] Demand-side economics relies on a fixed-price view of the economy, where the demand plays a key role in defining the future supply growth, which also allows for incentive implications of investment.

On these assumptions, supply side economists formulate the idea that a cut in marginal tax rates has a positive effect on economic growth.

[32] This led supply-siders to advocate large reductions in marginal income and capital gains tax rates to encourage greater investment, which would produce more supply.

[citation needed] The administration of Republican president Ronald Reagan promoted its fiscal policies as being based on supply-side economics.

[better source needed][38] As a result, Jason Hymowitz cited Reagan—along with Jack Kemp—as a great advocate for supply-side economics in politics and repeatedly praised his leadership.

[44] The bill was strongly opposed by Republicans, vigorously attacked by John Kasich and Minority Whip Newt Gingrich as destined to cause job losses and lower revenue.

[71] One benefit of a supply-side policy is that shifting the aggregate supply curve outward means prices can be lowered along with expanding output and employment.

Taxes act as a type of trade barrier or tariff that causes economic participants to revert to less efficient means of satisfying their needs.

[72] Supply-side economists have less to say on the effects of deficits and sometimes cite Robert Barro's work that states that rational economic actors will buy bonds in sufficient quantities to reduce long-term interest rates.

My reading of the academic literature leads me to believe that about one-third of the cost of a typical tax cut is recouped with faster economic growth.

"[75] In a 1992 article for the Harvard International Review, James Tobin wrote: "The 'Laffer curve' idea that tax cuts would actually increase revenues turned out to deserve the ridicule.

President Reagan argued that because of the effect depicted in the Laffer curve, the government could maintain expenditures, cut tax rates, and balance the budget.

[78] A 1999 study by University of Chicago economist Austan Goolsbee examined major changes in high-income tax rates in the United States from the 1920s onwards.

"[79] In 2015, one study found that in the past several decades, tax cuts in the U.S. seldom recouped revenue losses and had minimal impact on GDP growth.

They projected rapid growth, dramatic increases in tax revenue, a sharp rise in saving, and a relatively painless reduction in inflation.

This study was criticized by many economists, including Harvard Economics Professor Greg Mankiw, who pointed out that the CBO used a very low value for the earnings-weighted compensated labor supply elasticity of 0.14.

[107] The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that extending the Bush tax cuts beyond their 2010 expiration would increase the deficit by $1.8 trillion over 10 years.

[108] The CBO also completed a study in 2005 analyzing a hypothetical 10% income tax cut and concluded that under various scenarios there would be minimal offsets to the loss of revenue.

"[114] The New York Times reported in November 2018 that the Trump tax overhaul "has fattened the paychecks of most American workers, padded the profits of large corporations and sped economic growth."

The writers explained that "It's highly unusual for deficits...to grow this much during periods of prosperity" and that "the fiscal health of the U.S. is deteriorating fast, as revenues have declined sharply" (nearly $200 billion or about 6%) relative to the CBO forecast prior to the tax cuts.

Results for 2018 included: Analysis conducted by the Congressional Research Service on the first-year effect of the tax cut found that little if any economic growth in 2018 could be attributed to it.

[116][117] Growth in GDP, employment, worker compensation and business investment slowed during the second year following enactment of the tax cut, prior to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

[121] He also falsely asserted that the CBO had found the "entire $1.5 trillion tax cut is virtually paid for by higher revenues and better nominal GDP.

As part of the deleveraging initiative, the government also encouraged mergers and acquisitions, direct financing, and debt-to-equity swaps, resulting in the stabilization of corporate debt to GDP ratio.

[128] Increasing the supply of housing is a way to drive down prices, in contrast to demand-side economics which believes in subsidizing buyers or reducing demand with tight monetary policy.

in the United States

Labor is supply , money is demand