Symphonic poem

[4] Some piano and chamber works, such as Arnold Schoenberg's string sextet Verklärte Nacht, have similarities with symphonic poems in their overall intent and effect.

For example, The Swan of Tuonela (1895) is a tone poem from Jean Sibelius's Lemminkäinen Suite, and Vltava (The Moldau) by Bedřich Smetana is part of the six-work cycle Má vlast.

The first use of the German term Tondichtung (tone poem) appears to have been by Carl Loewe, applied not to an orchestral work but to his piece for piano solo, Mazeppa, Op.

"[6] Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann and Niels Gade achieved successes with their symphonies, putting at least a temporary stop to the debate as to whether the genre was dead.

[7] Between 1845 and 1847, the Belgian composer César Franck wrote an orchestral piece based on Victor Hugo's poem Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne.

The work exhibits characteristics of a symphonic poem, and some musicologists, such as Norman Demuth and Julien Tiersot, consider it the first of its genre, preceding Liszt's compositions.

The symphonic poem invented by Liszt had the main theme heard at the start of the piece, then develop through thematic transformation, never leaving behind musical coherence.

[24] Influenced by Liszt's efforts, Smetana began a series of symphonic works based on literary subjects—Richard III (1857–58), Wallenstein's Camp (1858–59) and Hakon Jarl (1860–61).

[12] Musicologist John Clapham writes that Smetana planned these works as "a compact series of episodes" drawn from their literary sources "and approached them as a dramatist rather than as a poet or philosopher.

"[25] He used musical themes to represent specific characters; in this manner he more closely followed the practice of French composer Hector Berlioz in his choral symphony Roméo et Juliette than that of Liszt.

[29] Clapham adds that in his musical depiction of scenery in these works, Smetana "established a new type of symphonic poem, which led eventually to Sibelius's Tapiola".

[30] Also, in showing how to apply new forms for new purposes, Macdonald writes that Smetana "began a profusion of symphonic poems from his younger contemporaries in the Czech lands and Slovakia", including Antonín Dvořák, Zdeněk Fibich, Leoš Janáček and Vítězslav Novák.

The first, which Macdonald variously calls symphonic poems and overtures,[28] forms a cycle similar to Má vlast, with a single musical theme running through all three pieces.

Four of them—The Water Goblin, The Noon Witch, The Golden Spinning Wheel and The Wild Dove—are based on poems from Karel Jaromír Erben's Kytice (Bouquet) collection of fairy tales.

[28][31] He also follows Liszt and Smetana's example of thematic transformation, metamorphosing the king's theme in The Golden Spinning Wheel to represent the wicked stepmother and also the mysterious, kindly old man found in the tale.

[28] Balakirev's other two symphonic poems, In Bohemia (1867, 1905) and Russia (1884 version) lack the same narrative content; they are actually looser collections of national melodies and were originally written as concert overtures.

Macdonald calls Modest Mussorgsky's Night on Bald Mountain and Alexander Borodin's In the Steppes of Central Asia "powerful orchestral pictures, each unique in its composer's output".

[34] Night on Bald Mountain, especially its original version, contains harmony that is often striking, sometimes pungent and highly abrasive; its initial stretches especially pull the listener into a world of uncompromisingly brutal directness and energy.

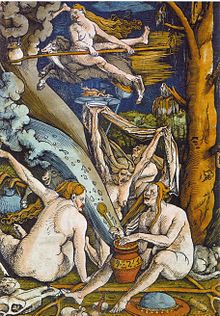

[35] Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov wrote only two orchestral works that rank as symphonic poems, his "musical tableau" Sadko (1867–92) and Skazka (Legend, 1879–80), originally titled Baba-Yaga.

[28] The Lyadov works' lack of purposeful harmonic rhythm (an absence less noticeable in Baba-Yaga and Kikimora due to a superficial but still exhilarating bustle and whirl) produces a sense of unreality and timelessness much like the telling of an oft-repeated and much loved fairy tale.

[28] (Tchaikovsky did not call Romeo and Juliet a symphonic poem but rather a "fantasy-overture", and the work may actually be closer to a concert overture in its relatively stringent use of sonata form.

[28] Socialist realism in the Soviet Union allowed program music to survive longer there than in western Europe, as typified by Dmitri Shostakovich's symphonic poem October (1967).

Paul Dukas' The Sorcerer's Apprentice follows the narrative vein of symphonic poem, while Maurice Ravel's La valse (1921) is considered by some critics a parody of Vienna in an idiom no Viennese would recognize as his own.

[40] Albert Roussel's first symphonic poem, based on Leo Tolstoy's novel Resurrection (1903), was soon followed by Le Poème de forêt (1904–06), which is in four movements written in cyclic form.

Therefore, other than Strauss and numerous concert overtures by others, there are only isolated symphonic poems by German and Austrian composers—Hugo Wolf's Penthesilea (1883–85), Alexander von Zemlinsky's Die Seejungfrau (1902-03) and Arnold Schoenberg's Pelleas und Melisande (1902–03).

[40] Alexander Ritter, who himself composed six symphonic poems in the vein of Liszt's works, directly influenced Richard Strauss in writing program music.

Strauss wrote on a wide range of subjects, some of which had been previously considered unsuitable to set to music, including literature, legend, philosophy and autobiography.

[40] In these works, Strauss takes realism in orchestral depiction to unprecedented lengths, widening the expressive functions of program music as well as extending its boundaries.

[44] As Hugh Macdonald points out in the New Grove (1980), "Strauss liked to use a simple but descriptive theme—for instance the three-note motif at the opening of Also sprach Zarathustra, or striding, vigorous arpeggios to represent the manly qualities of his heroes.

Composers included Arnold Bax and Frederick Delius in Great Britain; Edward MacDowell, Howard Hanson, Ferde Grofé and George Gershwin in the United States; Carl Nielsen in Denmark; Zygmunt Noskowski and Mieczysław Karłowicz in Poland and Ottorino Respighi in Italy.