History of science and technology in China

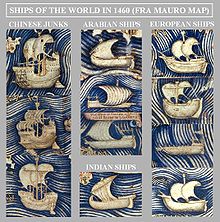

[citation needed] The Four Great Inventions, the compass, gunpowder, papermaking, and printing – were among the most important technological advances, only known to Europe by the end of the Middle Ages 1000 years later.

The Jesuit China missions of the 16th and 17th centuries introduced Western science and astronomy, while undergoing its own scientific revolution, at the same time bringing Chinese knowledge of technology back to Europe.

Needham further notes that the Han dynasty, which conquered the short-lived Qin, were made aware of the need for law by Lu Jia and by Shusun Tong, as defined by the scholars, rather than the generals.

While the exact mechanism is unclear, scholars think it incorporated the use of a differential gear in order to apply equal amount of torque to wheels rotating at different speeds, a device that is found in all modern automobiles.

[18] By AD 300, Ge Hong, an alchemist of the Jin dynasty, conclusively recorded the chemical reactions caused when saltpetre, pine resin and charcoal were heated together, in Book of the Master of the Preservations of Solidarity.

[citation needed] In the 7th century, book-printing was developed in China, Korea and Japan, using delicate hand-carved wooden blocks to print individual pages.

[23] Chinese illustrations were more realistic than in Byzantine manuscripts,[23] and detailed accounts from 1044 recommending its use on city walls and ramparts show the brass container as fitted with a horizontal pump, and a nozzle of small diameter.

[23] The records of a battle on the Yangtze near Nanjing in 975 offer an insight into the dangers of the weapon, as a change of wind direction blew the fire back onto the Song forces.

The first Song Emperor created political institutions that allowed a great deal of freedom of discourse and thought, which facilitated the growth of scientific advance, economic reforms, and achievements in arts and literature.

In 1070, Su Song also compiled the Ben Cao Tu Jing (Illustrated Pharmacopoeia, original source material from 1058 to 1061 AD) with a team of scholars.

[25] During the early half of the Song dynasty (960–1279), the study of archaeology developed out of the antiquarian interests of the educated gentry and their desire to revive the use of ancient vessels in state rituals and ceremonies.

[26] His contemporary Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) compiled an analytical catalogue of ancient rubbings on stone and bronze, which Patricia B. Ebrey says pioneered ideas in early epigraphy and archaeology.

[27] In accordance with the beliefs of the later Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886), some Song gentry—such as Zhao Mingcheng (1081–1129)—supported the primacy of contemporaneous archaeological finds of ancient inscriptions over historical works written after the fact, which they contested to be unreliable in regard to the former evidence.

Chinese alchemists searched for ways to make cinnabar, gold and other minerals water soluble so they could be ingested, such as using a solution of potassium nitrate in vinegar .

[33] Mongol rule under the Yuan dynasty saw technological advances from an economic perspective, with the first mass production of paper banknotes by Kublai Khan in the 13th century.

In 1259–1260 military alliance of the Franks knights of the ruler of Antioch, Bohemond VI and his father-in-law Hetoum I with the Mongols under Hulagu, in which they fought together for the conquests of Muslim Syria, taking together the city of Aleppo, and later Damascus.

[34] William of Rubruck, an ambassador to the Mongols in 1254–1255, a personal friend of Roger Bacon, is also often designated as a possible intermediary in the transmission of gunpowder know-how between the East and the West.

[38] As Toby E. Huff notes, pre-modern Chinese science developed precariously without solid scientific theory, while there was a lacking of consistent systemic treatment in comparison to contemporaneous European works such as the Concordance and Discordant Canons by Gratian of Bologna (fl.

[40] Sun Sikong (1015–1076) proposed the idea that rainbows were the result of the contact between sunlight and moisture in the air, while Shen Kuo (1031–1095) expanded upon this with description of atmospheric refraction.

Emperor Gaozong (reigned 649–683) of the Tang dynasty (618–907) commissioned the scholarly compilation of a materia medica in 657 that documented 833 medicinal substances taken from stones, minerals, metals, plants, herbs, animals, vegetables, fruits, and cereal crops.

[62] Shen Kuo's written work of 1088 also contains the first written description of the magnetic needle compass, the first description in China of experiments with camera obscura, the invention of movable type printing by the artisan Bi Sheng (990–1051), a method of repeated forging of cast iron under a cold blast similar to the modern Bessemer process, and the mathematical basis for spherical trigonometry that would later be mastered by the astronomer and engineer Guo Shoujing (1231–1316).

[76] Pascal's triangle was first illustrated in China by Yang Hui in his book Xiangjie Jiuzhang Suanfa (详解九章算法), although it was described earlier around 1100 by Jia Xian.

[82] The Wujing Zongyao military manuscript of 1044 listed the first known written formulas for gunpowder, meant for light-weight bombs lobbed from catapults or thrown down from defenders behind city walls.

One modern historian writes that in late Ming courts, the Jesuits were "regarded as impressive especially for their knowledge of astronomy, calendar-making, mathematics, hydraulics, and geography.

"[88] The Society of Jesus introduced, according to Thomas Woods, "a substantial body of scientific knowledge and a vast array of mental tools for understanding the physical universe, including the Euclidean geometry that made planetary motion comprehensible.

[91] It is thought that such works had considerable importance on European thinkers of the period, particularly among the Deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Christianity.

[citation needed] Other events such as Haijin, the Opium Wars and the resulting hate of European influence prevented China from undergoing an Industrial Revolution; copying Europe's progress on a large scale would be impossible for a lengthy period of time.

[citation needed] In his book Guns, Germs, and Steel, Jared Diamond postulates that the lack of geographic barriers within much of China—essentially a wide plain with two large navigable rivers and a relatively smooth coastline—led to a single government without competition.

[103]: 101 Beginning in 1964, China through the Third Front construction built a self-sufficient industrial base in its hinterlands as a strategic reserve in the event of war with the Soviet Union or the United States.

[105]: 180 Through its distribution of infrastructure, industry, and human capital around the country, the Third Front created favorable conditions for subsequent market development and private enterprise.