Religion in China

These may be natural deities belonging to the environment, or ancient progenitors of human groups, concepts of civility, or culture heroes, of whom many feature throughout Chinese history and mythology.

Fairbank suggests that the challenges created by the climate of the country's river floodplains fostered uncertainty among the people, which may have contributed to their tendency toward relatively impersonal religious creeds, like Buddhism, in contrast with the anthropocentric nature of Christianity.

In his view, the power of Tian is immanent, and responds positively to the sincere heart driven by the qualities of humaneness, rightness, decency and altruism that Confucius conceived of as the foundation needed to restore socio-political harmony.

Emperor Wu of Han formulated the doctrine of the Interactions Between Heaven and Mankind,[37] and of prominent fangshi, while outside the state religion the Yellow God was the focus of Huang-Lao religious movements which influenced primitive Taoism.

[40] By the end of the Eastern Han, the earliest record of a mass religious movement attests the excitement provoked by the belief in the imminent advent of the Queen Mother of the West in the northeastern provinces.

[43] Buddhism was introduced during the latter Han dynasty, and first mentioned in 65 CE, entering China via the Silk Road, transmitted by the Buddhist populations who inhabited the Western Regions, then Indo-Europeans (predominantly Tocharians and Saka).

[46] Both Buddhism and Taoism developed hierarchic pantheons which merged metaphysical (celestial) and physical (terrestrial) being, blurring the edge between human and divine, which reinforced the religious belief that gods and devotees sustain one another.

He notices that these authors work in the wake of a "Western evangelical bias" reflected in the coverage carried forward by popular media, especially in the United States, which rely upon a "considerable romanticisation" of Chinese Christians.

Southern provinces have experienced the most evident revival of Chinese folk religion,[115][116] although it is present all over China in a great variety of forms, intertwined with Taoism, fashi orders, Confucianism, Nuo rituals, shamanism and other religious currents.

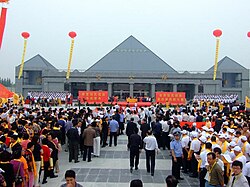

The folk religion of central-northern China (North China Plain), otherwise, is focused on the communal worship of tutelary deities of creation and nature as identity symbols, by villages populated by families of different surnames,[120] structured into "communities of the god(s)" (shénshè 神社, or huì 会, "association"),[121] which organise temple ceremonies (miaohui 庙会), involving processions and pilgrimages,[122] and led by indigenous ritual masters (fashi) who are often hereditary and linked to secular authority.

[123] Folk religious movements of salvation have historically been more successful in the central plains and in the northeastern provinces than in southern China, and central-northern popular religion shares characteristics of some of the sects, such as the great importance given to mother goddess worship and shamanism,[124] as well as their scriptural transmission.

Han Chinese culture embodies a concept of religion that differs from the one that is common in the Abrahamic traditions, which are based on the belief in an omnipotent God who exists outside the world and human race and has complete power over them.

A practice developed in the Chinese folk religion of post-Maoist China, that started in the 1990s from the Confucian temples managed by the Kong kin (the lineage of the descendants of Confucius himself), is the representation of ancestors in ancestral shrines no longer just through tablets with their names, but through statues.

By the words of Stephan Feuchtwang, in Chinese cosmology "the universe creates itself out of a primary chaos of material energy" (hundun 混沌 and qi), organising as the polarity of yin and yang which characterises any thing and life.

Yin and yang are the invisible and the visible, the receptive and the active, the unshaped and the shaped; they characterise the yearly cycle (winter and summer), the landscape (shady and bright), the sexes (female and male), and even sociopolitical history (disorder and order).

[193] Hao (2017) defined lineage temples as nodes of economic and political power which work through the principle of crowdfunding (zhongchou):[194] In China, many religious believers practice or draw beliefs from multiple religions simultaneously and are not exclusively associated with a single faith.

[217] China has a long history of sectarian traditions, called "salvationist religions" (救度宗教 jiùdù zōngjiào) by some scholars, which are characterized by a concern for salvation (moral fulfillment) of the person and the society, having a soteriological and eschatological character.

[223] These religions are characterized by egalitarianism, charismatic founding figures claiming to have received divine revelation, a millenarian eschatology and voluntary path of salvation, an embodied experience of the numinous through healing and cultivation, and an expansive orientation through good deeds, evangelism and philanthropy.

[235] Confucianism focuses on a this worldly awareness of Tian (天 "Heaven"),[236] the search for a middle way in order to preserve social harmony and on respect through teaching and a set of ritual practices.

[237] Joël Thoraval finds that Confucianism expresses on a popular level in the widespread worship of five cosmological entities: Heaven and Earth (Di 地), the sovereign or the government (jūn 君), ancestors (qīn 親) and masters (shī 師).

[239] The scholar Joseph Adler concludes that Confucianism is not so much a religion in the Western sense, but rather "a non-theistic, diffused religious tradition", and that Tian is not so much a personal God but rather "an impersonal absolute, like dao and Brahman".

[242] As defined by Stephan Feuchtwang, Heaven is thought to have an ordering law which preserves the world, which has to be followed by humanity by means of a "middle way" between yin and yang forces; social harmony or morality is identified as patriarchy, which is the worship of ancestors and progenitors in the male line, in ancestral shrines.

Ethics and appropriate behavior may vary depending on the particular school, but in general all emphasize wu wei (effortless action), "naturalness", simplicity, spontaneity, and the Three Treasures: compassion, moderation, and humility.

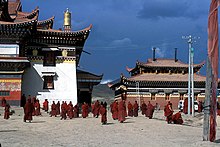

[273][274] In the pre-modern era, Tibetan Buddhism spread outside of Tibet primarily due to the influence of the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), founded by Kublai Khan, who ruled China, Mongolia, and parts of Siberia.

Tangmi, together with the broader religious tradition of Tantrism (in Chinese: 怛特罗 Dátèluō or 怛特罗密教 Dátèluó mìjiào; which may include Hindu forms of religion)[56]: 3 has undergone a revitalisation since the 1980s together with the overall revival of Buddhism.

It is pantheistic and deeply influenced by Chinese religion, sharing the concept of yin and yang representing, respectively, the realm of the gods in potentiality and the manifested or actual world of living things as a complementary duality.

The first is a grass-roots revival of cults dedicated to local deities and ancestors, led by shamans; the second way is a promotion of the religion on the institutional level, through a standardisation of Moism elaborated by Zhuang government officials and intellectuals.

[307] "Moism" refers to the dimension led by mogong (摩公), vernacular ritual specialists able to transcribe and read texts written in Zhuang characters and lead the worship of Buluotuo and the goddess Muliujia.

What Westerners referred to as Nestorianism flourished for centuries, until Emperor Wuzong of the Tang in 845 ordained that all foreign religions (Buddhism, Christianity and Zoroastrianism) had to be eradicated from the Chinese nation.

[197]: 51 The introduction of Islam (伊斯兰教 Yīsīlánjiào or 回教 Huíjiào) in China is traditionally dated back to a diplomatic mission in 651, eighteen years after Muhammad's death, led by Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas.

■ Chinese folk religion (and Confucianism , Taoism , and groups of Chinese Buddhism )

■ Buddhism tout court

■ Islam

■ Ethnic minorities' indigenous religions

■ Mongolian folk religion

■ Northeast China folk religion influenced by Tungus and Manchu shamanism , widespread Shanrendao