Tax haven

In contrast, countries with lower levels of secrecy but also low "effective" rates of taxation, most notably Ireland in the FSI rankings, appear in most § Tax haven lists.

Because of § Inflated GDP-per-capita (due to accounting BEPS flows), havens are prone to over-leverage (international capital misprice the artificial debt-to-GDP).

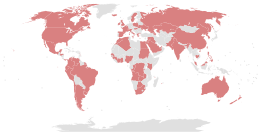

In July 2017, the University of Amsterdam's CORPNET group ignored any definition of a tax haven and focused on a purely quantitive approach, analysing 98 million global corporate connections on the Orbis database.

[64] Zucman pointed out that the CORPNET research under-represented havens associated with US technology firms, like Ireland and the Cayman Islands, as Google, Facebook and Apple do not appear on Orbis.

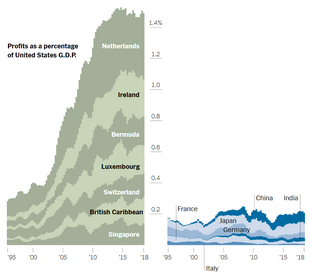

[65] These lists (Hines 2010, CORPNET 2017 and Zucman 2018), and others, which followed a purely quantitive approach, showed a firm consensus around the largest corporate tax havens.

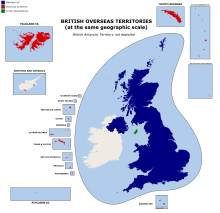

As discussed in § History, the United Kingdom created its first "non-resident company" in 1929, and led the Eurodollar offshore financial centre market post–World War II.

The studies capture the rise of Ireland and Singapore, both major regional headquarters for some of the largest BEPS tool users, Apple, Google and Facebook.

[106][107][108] In Q1 2015, Apple completed the largest BEPS action in history, when it shifted US$300 billion of IP to Ireland, which Nobel-prize economist Paul Krugman called "leprechaun economics".

In a June 2018 joint IMF report into the effect of BEPS flows on global economic data, eight of the above (excluding Switzerland and the United Kingdom) were cited as the world's leading tax havens.

[140][141][142] Henry did the study for the Tax Justice Network (TJN), and as part of his analysis, chronicled the history of past financial estimates by various organisations.

The artificial inflation of GDP can attract underpriced foreign capital (who use the "headline" Debt-to-GDP metric of the haven), thus producing phases of stronger economic growth.

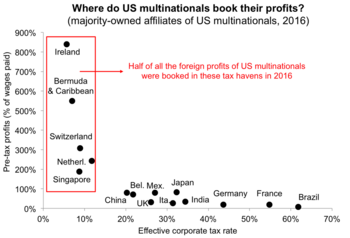

countries, 10% to the rest of the OECD, and 15% to developing countries (Tørsløv et al., 2018).In 2019, non-academic groups, such as the Council on Foreign Relations, realised the scale of U.S. corporate use of tax havens: Well over half the profits that American companies report earning abroad are still booked in only a few low-tax havens — places that, of course, are not actually home to the customers, workers, and taxpayers facilitating most of their business.

The 2017 TCJA seems to support this view with the U.S. exchequer being able to levy a 15.5% repatriation tax on over $1 trillion of untaxed offshore profits built up by U.S. multinationals with BEPS tools from non-U.S. revenues.

[176] Hines' research was cited by the Council of Economic Advisors ("CEA") in drafting the TCJA legislation in 2017, and advocating for moving to a hybrid "territorial" tax system framework.

[184][185][186] Ronen Palan has noted that even where tax havens started out as "trading centres", they can eventually become "captured" by "powerful foreign finance and legal firms who write the laws of these countries which they then exploit".

IP accounting enables the legal ownership of the software to be relocated to a tax haven where it can be revalued to being worth US$100 billion, which becomes the new price at which it is charged out against global profits.

In 2017, the University of Amsterdam's CORPNET research group published the results of their multi-year big data analysis of over 98 million global corporate connections.

CORPNET's Conduit OFCs contained several major jurisdictions considered OECD and/or EU tax havens, including the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Ireland.

[200] This SPV offers features including orphan structures, which is facilitated to support requirements for bankruptcy remoteness, which would not be appropriate in larger financial centres, as it could damage the local tax base, but are needed by banks in securitizations.

The source was French computer analyst Hervé Falciani who provided data on accounts held by over 100,000 clients and 20,000 offshore companies with HSBC in Geneva; the disclosure has been called "the biggest leak in Swiss banking history".

Le Monde called upon 154 journalists affiliated with 47 different media outlets to process the data, including The Guardian, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and the ICIJ.

[212][213] In 2015, 11.5 million documents totalling 2.6 terabytes, detailing financial and attorney-client information for more than 214,488 offshore entities, some dating back to the 1970s, that were taken from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, were anomalously leaked to German journalist Bastian Obermayer in Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ).

[214] In 2017, 13.4 million documents totalling 1.4 terabytes, detailing both personal and major corporate client activities of the offshore magic circle law firm Appleby, covering 19 tax havens, were leaked to the German reporters Frederik Obermaier and Bastian Obermayer in Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ).

They contain the names of more than 120,000 people and companies including Apple, AIG, Prince Charles, Queen Elizabeth II, the President of Colombia Juan Manuel Santos, and then-U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross.

In a report dated 15 June 2023,[216] certain chilling admissions were made by the Parliament of the European Union regarding the conduct and publicity surrounding the Pandora Papers data breach: [The Parliament] Stresses the importance of defending the freedom of journalists to report on issues of public interest without facing the threat of costly legal action, including when they receive confidential, secret or restricted documents, datasets or other materials, regardless of their origin.

(§2)[The Parliament] Regrets the lack of democratic accountability in the process of drawing up the "EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions for tax purposes"; recalls that the Council seems sometimes to be guided by diplomatic or political motives rather than objective assessments when deciding to move countries from the "grey list" to the "black list" and vice-versa; stresses that this undermines the credibility, predictability and usefulness of the lists; calls for Parliament to be consulted in the preparation of the list and for an extensive revision of the screening criteria (§78)[The Parliament] notes that despite the implementation of European and national legislation on beneficial ownership transparency, as reported by non-governmental organisations, the quality of data in some EU public registers requires improvement (§60)The various countermeasures that higher-tax jurisdictions have taken against tax havens can be grouped into the following types: In 2010, Congress passed the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), which requires foreign financial institutions (FFI) of broad scope – banks, stock brokers, hedge funds, pension funds, insurance companies, trusts – to report directly to the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) all clients who are U.S. persons.

FATCA also requires U.S. citizens and green card holders who have foreign financial assets in excess of $50,000 to complete a new Form 8938 to be filed with the 1040 tax return, starting with fiscal year 2010.

At the 2012 G20 Los Cabos summit, it was agreed that the OECD undertake a project to combat base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) activities by corporates.

An OECD BEPS Multilateral Instrument, consisting of "15 Actions" designed to be implemented domestically and through bilateral tax treaty provisions, was agreed upon at the 2015 G20 Antalya summit.

[82] Since the TCJA, Pfizer has guided global aggregate tax rates that are very similar to what they expected in their aborted 2016 inversion with Allergan plc in Ireland.