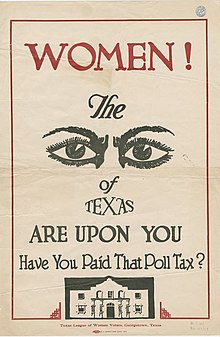

Women's poll tax repeal movement

[8] The ramifications were deeper than political disenfranchisement, because in states where juries were selected from those on the electoral roll, those who could not pay poll taxes were also denied the opportunity to serve or have their case evaluated by their peers.

Members of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs campaigned against Jim Crow laws – legal statutes regulating and enforcing racial segregation in the United States.

"[87] Other women who worked with Durr included Eleanor Bontecou, dean of Bryn Mawr College, who compiled statistical information; Frances Wheeler Sayler, a labor organizer and civil rights activist from Montana; and Sylvia Beitscher, Sarah d'Avila, and Katherine Shryver, who each served terms as executive secretary of the National Committee to Abolish the Poll Tax.

[48] Though some had success with their suits and were awarded damages, poll tax as a prerequisite for voting had effectively prevented them from participating, as by the time their cases were heard, the elections were over.

[104][105] Under the authority of this act, the Department of Justice was able to institute federal lawsuits against the states that still had local statutes that were excessively discriminatory in disenfranchising voters, by challenging their constitutionality.

[117] The 1949 effort to abolish the tax was a key part of the civil rights platform of President Harry S. Truman and was supported and campaigned for by Congresswoman Mary Teresa Norton, chair of the Committee on House Administration.

To tackle the problem, they gained support from the city clerk to create a mobile registration system and persuaded the National NuGrape Company to lend them a truck.

[142][143] In 1958, former governor Sid McMath was joined by state members of the League of Women Voters and labor unionists in petitioning for a constitutional amendment to eliminate the poll tax, which again failed.

[161] The federal Immigration Acts of 1921 and 1924 were passed to stem concerns that white authority was dwindling, and in effect extended segregation from blacks to other non-Anglo populations, creating separate public facilities for other non-white groups.

[171][172] The attempt was unsuccessful, and the poll tax system remained in effect until February 9, 1966, when a federal three-judge panel declared that it violated the Due Process Clause of the United States Constitution.

[173][174] Though the state law requiring payment of poll taxes in order to vote was rendered void by the decision, and the legislature passed a resolution that year to abolish it, the amendment was not formally approved until 2009, when it was reintroduced by Congresswoman Alma Allen.

Women activists not only continued to push for repeal, they began organizing fund raisers, such as bake sales, to raise money to assist their members in paying the taxes.

[101][188] A three-judge federal panel ruled that the Alabama statute requiring a poll tax as a prerequisite to voting was a violation of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on March 3, 1966.

[60] Attempts were made in 1941 and 1945 by the state legislature to revise the pay to vote method, but the 1941 effort was a failure and the 1945 bid resulted in a committee study, which delayed any action until 1949.

[205] The following year, the League conducted a public survey and, based upon its results, began a campaign, led by Carolyn Planck of Arlington, to eliminate the poll tax.

[215] On March 25, 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the state statute requiring poll taxes as a prerequisite for voting violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution's Equal Protection Clause and was therefore void.

[220] There was no action by the state legislature towards repeal, and so no state-wide referendum occurred,[221] although individual women filed legal cases challenging the poll tax statutes.

Attorney General Staples concurred with the allegations and Jones was awarded damages and a judgment was entered in her favor; this allowed the state to avoid a federal hearing on whether charging a poll tax was a valid voting qualification.

[233][234] She filed suit against the registrar of Arlington, Mary A. Thompson, claiming that the requirement to pay poll tax was enacted to disenfranchise black voters and violated federal equal protection laws.

[236] In 1964, Victoria Gray and Ceola Wallace, black women from Hattiesburg, Mississippi, challenged the state poll tax law on the grounds that it violated the recently passed Twenty-fourth Amendment by limiting their ability to vote.

[238] Also, in 1964, Annie E. Harper, who was joined by Gladys Berry and Curtis and Myrtle Burr, brought suit against the Virginia Board of Elections arguing that the poll tax denied them equal protection because they were poor.

Justice William O. Douglas wrote in the majority opinion, "Wealth, like race, creed, or color, is not germane to one's ability to participate intelligently in the electoral process.

[243][244] In 1966, Bessie Mae Huntley, Mary Helen Kohn, Joe Booker, and Robert Buchanan filed suit against the Holmes County, Mississippi Board of Supervisors.

They asked the Federal District Court in Jackson to restrain the county from implementing the bond issue until an election including all eligible voters could be held.

[257] The removal of barriers such as poll taxes, grandfather clauses,[Notes 8] and literacy tests contributed to increased registration and voter turnout, especially for blacks, women, and poor whites in the South.

[106] In other words, the Voting Rights Act gave federal oversight to election procedures, enabling the attorney general to challenge the use of disenfranchising provisions, such as poll taxes and literacy tests, on the grounds that they were discriminatory.

Using that power, in 1966 the federal courts nullified the remaining state statutes in Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas which required the payment of poll taxes as a prerequisite for voting.

[107] Contrary to pre-1970s popular and academic beliefs, American women's rights activists continued their activism during the interwar and post-war periods, as is demonstrated by their involvement in the movement to repeal poll taxes.

Key, a political scientist and historian of U.S. elections who was a recognized expert during the mid-century period, and other academics, minimized the role of women and African Americans in the poll tax reform movement.

[280][281] Works by other scholars such as the attorney and legal historian, Ronnie L. Podolefsky, and the history professor, Sarah Wilkerson Freeman, have re-analyzed the efforts to repeal poll taxes and concluded that women were a significant force.