Technetium

This silvery gray, crystalline transition metal lies between manganese and rhenium in group 7 of the periodic table, and its chemical properties are intermediate between those of both adjacent elements.

In 1871, Mendeleev predicted this missing element would occupy the empty place below manganese and have similar chemical properties.

Mendeleev gave it the provisional name eka-manganese (from eka, the Sanskrit word for one) because it was one place down from the known element manganese.

[11] This name caused significant resentment in the scientific community, because it was interpreted as referring to a series of victories of the German army over the Russian army in the Masuria region during World War I; as the Noddacks remained in their academic positions while the Nazis were in power, suspicions and hostility against their claim for discovering element 43 continued.

[12] The group bombarded columbite with a beam of electrons and deduced element 43 was present by examining X-ray emission spectrograms.

[12][17] The discovery of element 43 was finally confirmed in a 1937 experiment at the University of Palermo in Sicily by Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segrè.

[18] In mid-1936, Segrè visited the United States, first Columbia University in New York and then the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California.

[19] Segrè enlisted his colleague Perrier to attempt to prove, through comparative chemistry, that the molybdenum activity was indeed from an element with the atomic number 43.

In 1962, technetium-99 was isolated and identified in pitchblende from the Belgian Congo in very small quantities (about 0.2 ng/kg),[24] where it originates as a spontaneous fission product of uranium-238.

The natural nuclear fission reactor in Oklo contains evidence that significant amounts of technetium-99 were produced and have since decayed into ruthenium-99.

[24] Technetium is a silvery-gray radioactive metal with an appearance similar to platinum, commonly obtained as a gray powder.

The problem was exacerbated by the mutually enhanced solvent extraction of technetium and zirconium at the previous stage,[35] and required a process modification.

The majority of this material is produced by radioactive decay from [99MoO4]2−:[36][37] Pertechnetate (TcO−4) is only weakly hydrated in aqueous solutions,[38] and it behaves analogously to perchlorate anion, both of which are tetrahedral.

In concentrated sulfuric acid, [TcO4]− converts to the octahedral form TcO3(OH)(H2O)2, the conjugate base of the hypothetical triaquo complex [TcO3(H2O)3]+.

Technetium halides exhibit different structure types, such as molecular octahedral complexes, extended chains, layered sheets, and metal clusters arranged in a three-dimensional network.

Instead it has the structure of molybdenum tribromide, consisting of chains of confacial octahedra with alternating short and long Tc—Tc contacts.

More than a thousand of such periods have passed since the formation of the Earth, so the probability of survival of even one atom of primordial technetium is effectively zero.

In contrast to the rare natural occurrence, bulk quantities of technetium-99 are produced each year from spent nuclear fuel rods, which contain various fission products.

[77] The long half-life of technetium-99 and its potential to form anionic species creates a major concern for long-term disposal of radioactive waste.

Many of the processes designed to remove fission products in reprocessing plants aim at cationic species such as caesium (e.g., caesium-137) and strontium (e.g., strontium-90).

The primary danger with such practice is the likelihood that the waste will contact water, which could leach radioactive contamination into the environment.

[84] The recent shortages of medical technetium-99m reignited the interest in its production by proton bombardment of isotopically enriched (>99.5%) molybdenum-100 targets.

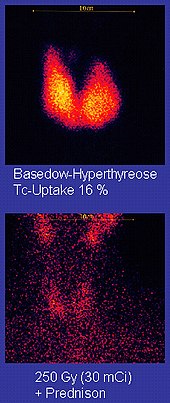

[28] The chemistry of technetium allows it to be bound to a variety of biochemical compounds, each of which determines how it is metabolized and deposited in the body, and this single isotope can be used for a multitude of diagnostic tests.

More than 50 common radiopharmaceuticals are based on technetium-99m for imaging and functional studies of the brain, heart muscle, thyroid, lungs, liver, gall bladder, kidneys, skeleton, blood, and tumors.

[90] The longer-lived isotope, technetium-95m with a half-life of 61 days, is used as a radioactive tracer to study the movement of technetium in the environment and in plant and animal systems.

[96] For this reason, pertechnetate has been used as an anodic corrosion inhibitor for steel, although technetium's radioactivity poses problems that limit this application to self-contained systems.

[96] The mechanism by which pertechnetate prevents corrosion is not well understood, but seems to involve the reversible formation of a thin surface layer (passivation).

[98] As noted, the radioactive nature of technetium (3 MBq/L at the concentrations required) makes this corrosion protection impractical in almost all situations.

The primary hazard when working with technetium is inhalation of dust; such radioactive contamination in the lungs can pose a significant cancer risk.

[101] Being close to noble metals, technetium is not very susceptible to corrosion, and during biofouling, its ability to self-cleanse has been recorded due to its radiotoxic effect on biota.