Territorial evolution of France

Meanwhile, the acquisitions of the counties of Dauphine in 1349, and Provence in 1486, saw at once both the Royal Domain and the Kingdom of France expand their frontiers into the south-east, with both having previously been fiefs of the neighbouring Holy Roman Empire.

However, their loyalty and obedience to him was hardly a likely prospect, and the attempts of English kings to both directly control and expand their French territories sparked a succession of wars during the Late Middle Ages.

Following the revolution, the new republic annexed the last remaining exclaves surrounded by France, such as the papal territory of Avignon, and conquered the former Austrian Netherlands (modern day Belgium) and Luxembourg.

Faced with war against virtually all the other nations in Europe, France reached by far its greatest territorial extent during the early nineteenth century when the Emperor Napoleon incorporated the Dutch Republic, Catalonia, Dalmatia, and parts of Germany and Italy into the First French Empire.

The division of the Carolingian Empire into West, Middle and East Francia at the Treaty of Verdun in 843 - with three grandsons of the emperor Charlemagne installed as their kings - was regarded at the time as a temporary arrangement, yet it heralded the birth of what would later become France and Germany.

Middle Francia broke apart almost immediately, its territory gradually incorporated into its Western and Eastern neighbours, while the West and East Frankish kings struggled to hold their realms together in the face of continual Viking raids and rebellious local lords.

The Germanic monarchy may have adopted the grander of Charlemagne's titles, but they were never able to consolidate their power enough to create a single, centralised state, and the Holy Roman Empire would remain a loose confederation of kingdoms, duchies, principalities and bishoprics throughout its history.

When a Muslim army burned the city of Barcelona in 985, Count Borrell II sought refuge in the Montserrat mountains and waited for help from the Frankish king, which never arrived, causing the Catalans great resentment towards the Franks.

Geoffrey Plantagenet was already Count of Anjou and the ruler of neighbouring Maine and Touraine when he married Empress Matilda, granddaughter of William the Conqueror and claimant to the throne of England.

Philip II was able to take advantage of this by first capturing the fortress of the Château Gaillard downstream from Paris, and then conquering the Duchy of Normandy which - along with Touraine and Anjou - he formally confiscated from king John of England in 1204.

[9] Emboldened by his father's success against the Plantagenets, Louis confiscated the counties of Poitou, Saintonge, Angoumois, and Périgord from Henry III of England, thereby shrinking the Duchy of Aquitaine down to Gascony in the far south-west.

Until the revolution, the province comprised eight of the modern French departments in Le Midi, and was able to preserve several of the County of Toulouse's own institutions, including a 'parliament' (a sovereign court of justice) and États (assemblies which voted on taxes and which decided on communal investments).

As their domain expanded, rather than rule their new acquisitions directly from Paris, several kings chose instead to create new dukedoms and grant them to a younger son, while the eldest continued to inherit the crown.

The House of Valois-Burgundy, effectively founded in 1363 when king John II awarded the Duchy of Burgundy to his youngest son Philip the Bold, gradually accumulated territories within both the Kingdom of France (such as Flanders and Artois in 1384) and the neighbouring Holy Roman Empire (such as Brabant in 1430 and Hainault in 1432).

The Dukes of Burgundy would eventually hold territory encompassing much of the Netherlands, including the major trading centres of Bruges, Brussels, Antwerp and Amsterdam, which made the Burgundian Court one of the wealthiest in Europe.

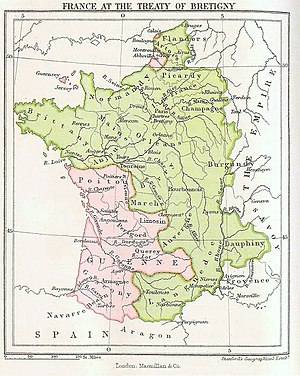

Edward agreed to renounce his claim to the French throne in exchange for a greatly enlarged Aquitaine and the port of Calais, which gave him control of the narrowest part of the English Channel.

Although a period of relative peace between England and France then ensued during the reign of Charles VI, he proved a weak and ineffective ruler prone to bouts of severe mental illness.

Reasserting his great-grandfather Edward III's claim to the French throne, his victory at Agincourt (1415) wiped out most of Charles VI's best knights, and enabled him to conquer Normandy and parts of the île de France.

The French victory at Castillon in 1453 marked not only the end of the Hundred Years' War, but to three centuries of English rule in Gascony, finally bringing the south-west of France under royal control.

Both the succession of the Duchy of Burgundy, and the desire to gain a foothold in Italy, were the principal causes of the first of a series of conflicts with the ruling dynasty of Austria and the Holy Roman Empire, the Habsburgs.

Louis was determined not only to gain direct control over Flanders - a French fief since the days of West Francia - but to seize Mary's other lands in the low countries, which included the wealthy cities of Antwerp and Amsterdam.

The treaty of Lyon, signed in 1601, let Charles Emmanuel keep Saluzzo but handed Bresse, Bugey, Valromey and the Pays de Gex - which together constitute the modern Ain department - to France which, crucially, closed off one of the Alpine valleys used by the Spanish Road.

This brought France into the Thirty Years' War on the side of Sweden, the Dutch Republic and several German states, already fighting the Imperial forces of the Holy Roman Empire (still ruled by the Austrian Habsburgs) and Spain.

Together with Louis' purchase of Dunkirk from king Charles II of England and Scotland for £320,000 in 1662 (the English having earlier captured the town from the Spanish) - this all but marked the limit of France's expansion in the north, apart from a twenty-year period during the revolutionary/Napoleonic era.

The Peace of Utrecht that ended the war, intending to preserve a balance of power on the continent, forced Philip and his heirs to cede any claim to the throne of France, guaranteeing the two kingdoms and their empires could never be ruled by the same person.

The fortified towns to the immediate north of the Duchy of Lorraine - Montmédy, Thionville, Longwy and Saarlouis - were intended to isolate it from the other states in the Holy Roman Empire, in particular the Austrian Netherlands, and ultimately undermine the independence of the dukes.

[10] But an opportunity would present itself in 1736, upon the marriage of Duke Francis III to the heiress of the Austrian House of Habsburg Maria Theresa, which took place at a time when Austria was fighting the War of Polish succession against Spain and Sardinia.

Francis agreed to leave Lorraine to the recently deposed King of Poland and Louis XV's father-in-law, Stanisław Leszczyński, so that it would merge with the French crown after his death.

After the proclamation of an independent Corsican Republic, and having been all but driven from the island but for two coastal forts, by 1767 it was clear the financially exhausted Genoese - who had also just been humiliated in the War of Austrian Succession - would not be able to repay France, and so offered to cede their claim to Corsica in exchange for their debt being annulled.

This provided a timely opportunity for Louis XV, who had hoped to establish a foothold in the Mediterranean by capturing British-held Menorca during the Seven Years' War, but had been forced to cede it back to Britain (along with almost all of France's North American and Asian colonies) at the 1763 Treaty of Paris.

West Francia Middle Francia East Francia