Madonna (art)

In Christian art, a Madonna (Italian: [maˈdɔnna]) is a religious depiction of the Blessed Virgin Mary in a singular form or sometimes accompanied by the Child Jesus.

The term Madonna in the sense of "picture or statue of the Virgin Mary" enters English usage in the 17th century, primarily in reference to works of the Italian Renaissance.

"Madonna" may be generally used of representations of Mary, with or without the infant Jesus, where she is the focus and central figure of the image, possibly flanked or surrounded by angels or saints.

Other types of Marian imagery that have a narrative context, depicting scenes from the Life of the Virgin, e.g. the Annunciation to Mary, are not typically called "Madonna".

[4] These names signal both the increased importance of the cult of the virgin and the prominence of art in service to Marian devotion during the late medieval period.

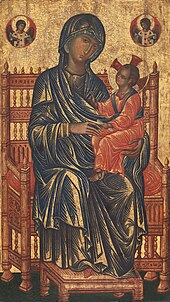

[17] In the West, hieratic Byzantine models were closely followed in the Early Middle Ages, but with the increased importance of the cult of the Virgin in the 12th and 13th centuries a wide variety of types developed to satisfy a flood of more intensely personal forms of piety.

There was a great expansion of the cult of Mary after the Council of Ephesus in 431, when her status as Theotokos ("God-bearer") was confirmed; this had been a subject of some controversy until then, though mainly for reasons to do with arguments over the nature of Christ.

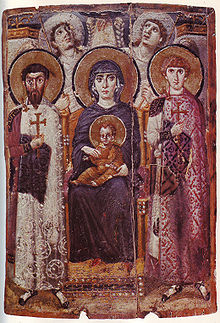

The image at Mount Sinai succeeds in combining two aspects of Mary described in the Magnificat, her humility and her exaltation above other humans, and has the Hand of God above, up to which the archangels look.

[18] At this period the iconography of the Nativity was taking the form, centred on Mary, that it has retained up to the present day in Eastern Orthodoxy, and on which Western depictions remained based until the High Middle Ages.

[20] Very few early images of the Virgin Mary survive, though the depiction of the Madonna has roots in ancient pictorial and sculptural traditions that informed the earliest Christian communities throughout Europe, Northern Africa and the Middle East.

Byzantium (324–1453) saw itself as the true Rome, if Greek-speaking, Christian empire with colonies of Italians living among its citizens, participating in Crusades at the borders of its land, and ultimately, plundering its churches, palaces and monasteries of many of its treasures.

Later in the Middle Ages, the Cretan school was the main source of icons for the West, and the artists there could adapt their style to Western iconography when required.

Another, a splintered, repainted ghost of its former self, is venerated at the Pantheon, that great architectural wonder of the Ancient Roman Empire, that was rededicated to Mary as an expression of the Church's triumph.

Some images of the Madonna were paid for by lay organizations called confraternities, who met to sing praises of the Virgin in chapels found within the newly reconstructed, spacious churches that were sometimes dedicated to her.

Its expense registers in the use of thin sheets of real gold leaf in all parts of the panel that are not covered with paint, a visual analogue not only to the costly sheaths that medieval goldsmiths used to decorate altars, but also a means of surrounding the image of the Madonna with illumination from oil lamps and candles.

Often referred to as the Rucellai Madonna (c. 1285), the panel painting towers over the spectator, offering a visual focus for members of the Laudesi confraternity to gather before it as they sang praises to the image.

In turn, a modestly scaled image of the Madonna as a half-length figure holding her son in a memorably intimate depiction, is to be found in the National Gallery of London.

Sometimes, the Madonna's complex bond with her tiny child takes the form of a close, intimate moment of tenderness steeped in sorrow where she only has eyes for him.

While the 15th and 16th centuries were a time when Italian painters expanded their repertoire to include historical events, independent portraits and mythological subject matter, Christianity retained a strong hold on their careers.

Some of the most eminent 16th-century Italian painters to turn to this subject were Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael,[note 1] Giorgione, Giovanni Bellini and Titian.

As a commemorative image, the Pietà became an important subject, newly freed from its former role in narrative cycles, in part, an outgrowth of popular devotional statues in Northern Europe.

At the culmination of his mission, in 629 CE, Muhammad conquered Mecca with a Muslim army, with his first action being the "cleansing" or "purifying" of the Kaaba, wherein he removed all the pre-Islamic pagan images and idols from inside the temple.

According to reports collected by Ibn Ishaq and al-Azraqi, Muhammad did, however, protectively put his hand over a painting of Mary and Jesus, and a fresco of Abraham in order to keep them from being effaced.

[31][32] In the words of the historian Barnaby Rogerson, "Muhammad raised his hand to protect an icon of the Virgin and Child and a painting of Abraham, but otherwise his companions cleared the interior of its clutter of votive treasures, cult implements, statuettes and hanging charms.

But Quraysh were more or less insensitive to this contrast: for them it was simply a question of increasing the multitude of idols by another two; and it was partly their tolerance that made them so impenetrable.... Apart from the icon of the Virgin Mary and the child Jesus, and a painting of an old man, said to be Abraham, the walls inside had been covered with pictures of pagan deities.

[36][37] Historian Anant Dhume, in his book 'The Cultural History of Goa from 10,000 BC to 1352 AD', compares the idol with the image of Madonna and the Christ child because of the similarities.

[39] "The Portuguese had settled with the aim to dominate the spice trade and spread their Christian faith, and these small, portable ivory statues would embellish the church altars and Goan homes, and were also transported abroad serving to fulfil their later project.

"[39] The Jesuits sourced small paintings, prints and sculptures from Europe for the Indian sculptors to use as reference, and the indigenous artists used their own traditions for fashioning such figures.

"[41] Artists such as Jamini Roy also adopted this image, and Jesus and Mary would feature in the canvases of Tyeb Mehta, Krishnen Khanna, Madhvi Parekh and others in ways that provide a commentary on, and glimpse of the Indian social scene.

[41] "These remain examples of how in art and in faith traditions merge, so do symbols and images, giving birth to syncretic cultures that testify the ravages of communal hate, man-made differences and orthodox interpretations".