The Malay Archipelago

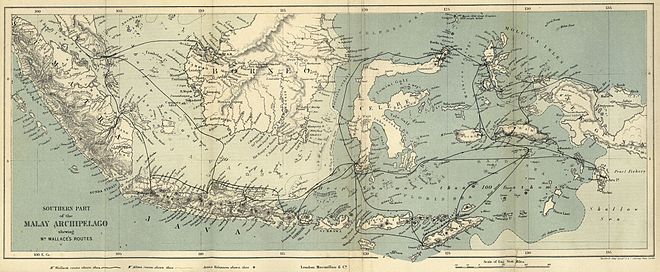

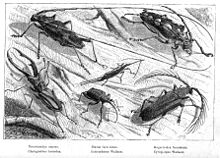

The book describes each island that he visited in turn, giving a detailed account of its physical and human geography, its volcanoes, and the variety of animals and plants that he found and collected.

Nearly all agreed that he had provided an interesting and comprehensive account of the geography, natural history, and peoples of the archipelago, which little was known about to readers at the time, in addition to the extensive breadth of specimens collected.

In 1847, Wallace and his friend Henry Walter Bates, both in their early twenties,[a] agreed that they would jointly make a collecting trip to the Amazon "towards solving the problem of origin of species".

It was based on Darwin's own long collecting trip on HMS Beagle, its publication precipitated by a famous letter from Wallace, sent during the period covered by The Malay Archipelago while he was staying in Ternate, which described the theory of evolution by natural selection in outline.

[2]) Wallace and Bates had been inspired by reading the American entomologist William Henry Edwards's pioneering 1847 book A Voyage Up the River Amazon, with a residency at Pará.

Instead he confines himself to the "interesting facts of the problem, whose solution is to be found in the principles developed by Mr. Darwin",[P 2] so from a scientific point of view, the book is largely a descriptive natural history.

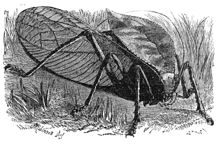

I trembled with excitement as I saw it coming majestically towards me,... and was gazing, lost in admiration, at the velvet black and brilliant green of its wings, seven inches across, its golden body, and crimson breast...

The reviewer remarks that the portrait "would as well suit a Papuan of the south-east coast of New Guinea as any of those whom Mr. Wallace saw", noting however that the southern tribes are more varied in skin colour.

The reviewer disagrees with Wallace about the extension of this "Papuan race" as far as Fiji, noting that there are or were people like that in Tasmania, but that their features and height varied widely, perhaps forming a series.

[12] Sir Roderick Murchison, giving a speech at the Royal Geographical Society, felt able to "feel a pride" in Wallace's success, and in the "striking contributions" made to science.

He takes interest in "Wallace's line" which he calls "this ingenious speculation", with "the two faunas wonderfully contrasted" either side of the deep channel between Borneo and Celebes, or Bali and Lombok.

However, Murchison states his disagreement with Wallace's support for James Hutton's principle of uniformitarianism, that "all former changes of the outline of the earth were produced slowly", opining that the Bali–Lombok channel probably formed suddenly.

He mentions in one sentence that the book contains "interesting and important facts" on physical geography, native inhabitants, climate and products of the archipelago, and describes Wallace as a great naturalist and a "most attractive writer".

[13] One of the shortest reviews was in The Ladies' Repository, which found it a highly valuable and intensely interesting contribution to our knowledge of a part of the world but little known in Europe or America.

He is an enthusiastic naturalist, a geographer, and geologist, a student of man and nature.The reviewer notes the region is "of terrific grandeur, parts of it being perpetually illuminated by discharging volcanoes, and all of it frequently shaken with earthquakes."

[15] The American Quarterly Church Review admires Wallace's bravery in going alone among the "barbarous races" in a "villainous climate" with all the hardships of travel, and his hard work in skinning, stuffing, drying and bottling so many specimens.

[16] The Australian Town and Country Journal begins by stating that[17] Mr. Wallace is generally understood to be the originator of the theory of "Natural Selection" as propounded by Mr. Darwin, and certainly .. he brings numerous phenomena which he regards as illustrative of that theory very vividly under the notice of his readers, and that, too, as if he were but a disciple of Mr. Darwin, and not an original discoverer.and quickly makes clear that it objects to Wallace's doubts about "indications of design" in plants.

[17] The review quotes a paragraph that paints "a picture of country life in the Celebes", where Wallace describes his host, a Mr. M., who relied on his gun to supply his table with wild pigs, deer, and jungle fowl, while enjoying his own milk, butter, rice, coffee, ducks, palm wine and tobacco.

However, the Australian reviewer doubted Wallace's judgement about flavours, given that he praised the Durian fruit, namely that it tastes of custard, cream cheese, onion sauce, brown sherry "and other incongruities", whereas "most Europeans" found it "an abomination".

It concludes that he covers almost every natural phenomenon he came across "with the accuracy and discriminating sagacity of an accomplished naturalist", and explains that the "great charm" of the book is "a truthful simplicity" which inspires confidence.

Radau notes the many deaths from volcanic eruptions in the archipelago, before explaining the similarity of the fauna of Java and Sumatra with that of central Asia, while that of the Celebes carries the mark of Australia, seeming to be the last representatives of another age.

Radau describes Wallace's experiences in Singapore, where goods were far cheaper than in Europe – wire, knives, corkscrews, gunpowder, writing-paper, and he remarks on the spread of the Jesuits into the interior, though the missionaries had to live on just 750 francs a year.

[20] Tim Radford, writing in The Guardian,[21] considers that The Malay Archipelago shows Wallace to be "an extraordinary figure", since he is an adventurer who does not present himself as adventurous; he is a Victorian Englishman abroad with all the self-assurance but without the lordly superiority of the coloniser; he is the chronicler of wonders who refuses to exaggerate, or to believe anybody else's improbable marvels: what he can see and examine (and, very often, shoot) is wonder enough for him.Radford finds "delights on every page", such as the Wallace line between the islands of Bali and Lombok; the sparkling observations, like "the river bed 'a mass of pebbles, mostly pure white quartz, but with abundance of jasper and agate'"; the detailed but lively accounts of natural history and physical geography; the respectful and friendly attitude to the native peoples such as the hill Dyaks of Borneo; and his unclouded observations of human society, such as the way a Bugis man in Lombok runs amok, where Wallace[21] begins to reflect on the possible satisfactions of mass murder as a form of honourable suicide for the brooding and resentful man who 'will not put up with such cruel wrongs, but will be revenged on mankind and die like a hero.

'Robin McKie, in The Observer,[22] writes that the common view of Wallace "as a clever, decent cove who knew his place" as second fiddle to Charles Darwin is rather lopsided.

[22] The researcher Charles Smith rates the Malay Archipelago as "Wallace's most successful work, literarily and commercially", placing it second only to his Darwinism (1889) among his books for academic citations.