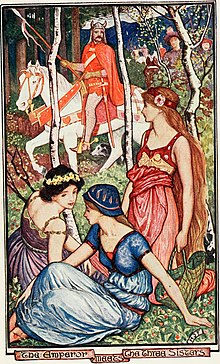

The Three Golden Children (folklore)

[3] Alternate names for the tale type are The Three Golden Sons, The Bird of Truth, Portuguese: Os meninos com uma estrelinha na testa, lit.

Meanwhile, the children are either hidden by a servant of the castle (gardener, cook, butcher) or cast into the water, but they are found and brought up at a distance from the father's home by a childless foster family (fisherman, miller, etc.).

Soon enough, the children move next to the palace where the king lives, and either the aunts, or grandmother realize their nephews/grandchildren are alive and send the midwife (or a maid; a witch; a slave) or disguise themselves to tell the sister that her house needs some marvellous items, and incite the girl to convince her brother(s) to embark on the (perilous) quest.

[18] German-Chilean philologist Rodolfo Lenz [es], complementing Cosquin's study, remarked that the elder sisters promise practical things, like cooking a grand meal, weaving such a garment for the king, sewing a special piece of clothing, etc.

[19] Similarly, French ethnologist Camille Lacoste-Dujardin [fr], in regards to a Kabylian variant, noted that the sisters' jealousy originated from their perceived infertility, and that their promises of grand feats of domestic chores were a matter of "capital importance" to them.

[25] In a brief summary:[23][26] a lord encounters a mysterious woman (clearly a swan maiden or fairy) in the act of bathing, while clutching a gold necklace, they marry and she gives birth to a septuplet, six boys and a girl, with golden chains about their necks.

"[23] The motif of the heroine persecuted by the queen, on false pretenses, also happens in Istoria della Regina Stella e Mattabruna,[27] a rhyming story of the ATU 706 type (The Maiden Without Hands).

[29] French scholar Gédeon Huet commented on a motif of the Dolopathos tale: near the beginning of the story, after she makes love to the human lord under the veil of night, the strange maiden (called nympha in the Latin text) knows beforehand she will give birth to seven children, six boys and a girl.

[36] Likewise, Emmanuel Cosquin listed that the motif of the "coffre flottant" ("The Floating Chest")[37][38] shows parallels with mythological accounts: Muslim/Javanese Raden Pakou, Assyro-Sumerian king Sargon, Hindu epic hero Karna.

[34] 19th-century India-born author Maive Stokes noted that the motif of children born with stars, moon or a sun in some part of their bodies occurred to heroes and heroines of both Asian and European fairy tales.

[43] Literary historian Reinhold Köhler [de] noted another set of motifs that mark the wonder children: the presence of a chain of gold or silver around their necks or on their skin.

[60] In addition, Bulgarian researcher Vanya Mateeva draws a parallel between the folkloric notion of a person's fate written on the front and the children's luminous or astral birthmarks on their foreheads, which seem to predict a grand destiny for them.

[35] Furthermore, Russian professor Khemlet Tat'yana Yur'evna suggests that the presence of the astronomical motifs on the children's bodies possibly refer to their connection to a celestial or heavenly realm.

[61] In a later study, Khemlet argues that variants of later tradition gradually lose the fantasy elements and a more realistic narrative emerges, with the fantastical becoming unreal and with more development of the characters' psychological state.

Russian folklorist Lev Barag [ru] noted two different formats: the first one, "legs of gold up the knee, arms of silver up to the elbow", and the second one, "the singing tree and the talking bird".

[86] In an extended version from a Breton source, called L'Oiseau de Vérité,[87] the youngest triplet, a king's son, listens to the helper (an old woman), who reveals herself to be a princess enchanted by her godmother.

[93] Texan researcher Warren Walker and Mongolist Charles Bawden ascribe some antiquity to the tale type, due to certain "primitive" elements, such as "the alleged birth of an animal or monster to a woman".

[94][d] Due to the great popularity of the tale in the Arab world, according to Ibrahim Muhawi, Yoel Shalom Perez and Judith Rosenhouse,[96][97] some have theorized that the Middle East is the possible point of its origin or dispersal.

[98] On the other hand, Joseph Jacobs, in his notes on Europa's Fairy Book, proposed a European provenance, based on the oldest extant version registered in literature (Ancilotto, King of Provino).

[101] Russian scholar Yuri Berezkin suggested that the first part of the tale (the promises of the three sisters and the substitution of babies for animals/objects) may find parallels in stories of the indigenous populations of the Americas.

[111][f] According to Waldemar Liungman, Johannes Østrup was also of the notion that tale type 707, "Drei Schwestern wollen den König haben" ("Three sisters wish to marry the king"), originated from a Persian source.

[115][116] The tale of Padmavati's birth—contained within the Mahāvastu[117]—is also curious: on a hot summer day, seer Mandavya puts away a pot with urine and semen and a doe drinks it, thinking it to be water.

[122][123] In this tale, titled Die Verkörperung des Arja Palo (Avalokitas'wara oder Chongschim Bodhissatwa) als Königssöhn Erdeni Charalik, princess Ssamantabhadri, daughter of king Tegous Tsoktou, goes to bathe with her two female slaves in the river.

[124][125][h] In a second tale from the Tripitaka, titled Les cinq cents fils d'Udayana ("The Five Hundred Sons of Udayana"), an ascetic named T'i-po-yen (Dvaipayana) urinates on a rock.

[147][148][i] Bottigheimer, Jack Zipes, Paul Delarue and Marie-Louise Thénèze register two ancient French literary versions: Princesse Belle-Étoile et Prince Chéri, by Mme.

[106][150][151] Late 19th-century and early 20th-century scholars (Joseph Jacobs, Teófilo Braga, Francis Hindes Groome) had noted that the story was widespread across Europe, the Middle East and India.

[152][153][154][155] Portuguese writer Braga noticed its prevalence in Italy, France, Germany, Spain and in Russian and Slavic sources,[156] while Groome listed its incidence in the Caucasus, Egypt, Syria and Brazil.

[159] In the same vein, Bulgarian folklorist Lyubomira Parpulova [bg] observed "similar notions" between the tale type 707, "The children with the wonderful features", and the Bulgarian/South Slavic folk song about a "walled-up wife".

[160] Commenting on a Greek variant he collected, Austrian consul Johann Georg von Hahn noted the punishment of the mother by walling her, and related the motif to Slavic legends.

[176] French historian François Delpech [fr] noted that strange birthmarks in folktales indicated a supernatural or royal origin of the characters, and mentioned the tale type in that regard.