Theatre of Scotland

Notable theatrical institutions include the National Theatre of Scotland, the Citizens Theatre of Glasgow and the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (formerly RSAMD), whose alumni include noted performers and directors Robert Carlyle, Tom Conti, Sheena Easton, John Hannah, Daniela Nardini, Hannah Gordon, Phyllis Logan and Ian McDiarmid.

Medieval Scotland probably had its own Mystery plays, often performed by craft guilds, like one described as ludi de ly haliblude and staged at Aberdeen in 1440 and 1445 and which was probably connected with the feast of Corpus Christi, but no texts are extant.

[3] Up-helly-aa, a Shetland festival appealing to Viking heritage, only took its modern form out of "mischief" of guising, tar-barrelling and other activities in the 1870s as part of a Romantic revival.

They continued into the seventeenth century, with parishioners in Aberdeen reproved for parading and dancing in the street with bells at weddings and Yule in 1605, Robin Hood and May plays at Kelso in 1611 and Yuletide guising at Perth in 1634.

[11] A masque by Buchanan and a spectacular fire drama devised and directed by Bastian Pagez were among the entertainments staged to celebrate the baptism of Prince James at Stirling Castle in December 1566.

[16] Costume for court masques, performed at the weddings of prominent courtiers including James Stewart, 1st Lord Doune, was managed by the wardrobe servant Servais de Condé.

[22] The loss of a royal court when James VI inherited the crown of England in 1603 meant there was no force to counter the Kirk's dislike of theatre, which struggled to survive in Scotland.

In 1663 Edinburgh lawyer William Clerke wrote Marciano or the Discovery, a play about the restoration of a legitimate dynasty in Florence after many years of civil war.

James Thompson's plays often dealt with the contest between public duty and private feelings, and included Sophonisba (1730), Agamemnon (1738) and Tancrid and Sigismuda (1745), the last of which was an international success.

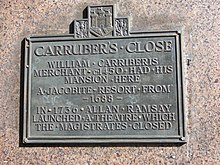

[31] The Court of Session reversed the magistrates' pleas, but Rev Robert Wodrow complained of plays as "seminaries of idleness, looseness and sin.

"[31] A pamphlet of the time described actors as, "the most profligate wretches and vilest vermin that hell ever vomited out... the filth and garbage of the earth, the scum and stain of human nature, the excrement and refuse of all mankind.

Towards the end of the century there were "closet dramas", primarily designed to be read, rather than performed, including work by James Hogg (1770–1835), John Galt (1779–1839) and Joanna Baillie (1762–1851), often influenced by the ballad tradition and Gothic Romanticism.

The play was a remarkable success in both Scotland and England for decades, attracting many notable actors of the period, such as Edmund Kean, who made his debut in it.

It may have been this persecution which drove Home to write for the London stage, in addition to Douglas' success there, and stopped him from founding the new Scottish national theatre that some had hoped he would.

[40][41] It made out a clear parallel between John of England and George III of Great Britain, and for that reason the censorship of the Lord Chamberlain had prevented its production on the London stage.

De Monfort was successfully performed in Drury Lane, London before knowledge of her identity emerged and the prejudice against women playwrights began to affect her career.

[46] Baillie's Highland themed The Family Legend was first produced in Edinburgh in 1810 with the help of Scott, as part of a deliberate attempt to stimulate a national Scottish drama.

[1][49] Locally produced drama in this period included John O' Arnha, adapted from the poem by George Beattie by actor-manager Charles Bass and poet James Bowick for the Theatre Royal in Montrose in 1826.

[52] In the second half of the century the development of Scottish theatre was hindered by the growth of rail travel, which meant English tour companies could arrive and leave more easily for short runs of performances.

Barrie is often linked to the Kailyard movement and his early plays such as Quality Street (1901) and The Admirable Crichton (1902) deal with temporary inversions of the normal social order.

As well as drawing on his medical experience, as in The Anatomist (1930), his plays included middle class satires such as The Sunlight Sonata (1928) and often called on biblical characters such as devils and angels, as in Mr. Bolfry (1943).

[61] The shift to drama that focused on working class life in the post-war period gained momentum with Robert McLeish's The Gorbals Story (1946), which dealt with the immense social problems of urban Scotland.

[72] In 1985, David Purves's The Puddok an the Princess, a Scots language version of The Frog Prince, won an Edinburgh Fringe First Award for Charles Nowosielski's Theatre Alba.

[74] Iain Moireach's plays also used humour to deal with serious subjects, as in Feumaidh Sinn a Bhith Gàireachdainn (We Have to Laugh, 1969), which focused on threats to the Gaelic language.

The Scottish Arts Council encouraged theatre companies to function as business, finding funding in ticket sales and commercial sponsorship.

[81] Mull Theatre moved into new premises at Druimfin in 2008, and in 2013 partnered with arts centre An Tobar to form Comar, a multi-arts organisation that produces, presents and develops creative work.

Under the direction of Jackie Wylie, The Arches staged performances such as DEREVO's Natura Morte, Nic Green's Trilogy and Linder Sterling's Darktown Cakewalk.

"[96] Hurley and his collaborators, all prominent in the Yes campaign, presented a rousing patchwork of song and monologue which nodded to John McGrath while extending his socialist legacy into a new century.

Other significant works of the early 21st century include Zinnie Harris’ Further than the Furthest Thing (2000), Decky Does A Bronco by Douglas Maxwell (2000), David Harrower’s Blackbird (2005), Sunshine on Leith by Stephen Greenhorn (2007), and historical trilogy The James Plays by Rona Munro (2014).

[110] The Game's a Bogey discussed the life of John MacLean, amongst other things, but resorted to obvious joke names, such as Sir Mungo McBungle for a failed industrialist, and Andy McChuckemup for a Glaswegian wheeler dealer.