Theatre of ancient Greece

At its centre was the city-state of Athens, which became a significant cultural, political, and religious place during this period, and the theatre was institutionalised there as part of a festival called the Dionysia, which honoured the god Dionysus.

Being a winner of the first theatrical contest held in Athens, he was the exarchon, or leader,[5] of the dithyrambs performed in and around Attica, especially at the Rural Dionysia.

Under the influence of heroic epic, Doric choral lyric and the innovations of the poet Arion, it had become a narrative, ballad-like genre.

Because of these, Thespis is often called the "Inventor of Tragedy"; however, his importance is disputed, and Thespis is sometimes listed as late as 16th in the chronological order of Greek tragedians; the statesman Solon, for example, is credited with creating poems in which characters speak with their own voice, and spoken performances of Homer's epics by rhapsodes were popular in festivals prior to 534 BC.

[6] Thus, Thespis's true contribution to drama is unclear at best, but his name has been given a longer life in English as a common term for performer—i.e., a "thespian."

While no drama texts exist from the sixth century BC, the names of three competitors besides Thespis are known: Choerilus, Pratinas, and Phrynichus.

Herodotus reports that "the Athenians made clear their deep grief for the taking of Miletus in many ways, but especially in this: when Phrynichus wrote a play entitled The Fall of Miletus and produced it, the whole theatre fell to weeping; they fined Phrynichus a thousand drachmas for bringing to mind a calamity that affected them so personally and forbade the performance of that play forever.

[8] Until the Hellenistic period, all tragedies were unique pieces written in honour of Dionysus and played only once; what is primarily extant today are the pieces that were still remembered well enough to have been repeated when the repetition of old tragedies became fashionable (the accidents of survival, as well as the subjective tastes of the Hellenistic librarians later in Greek history, also played a role in what survived from this period).

After the Achaemenid destruction of Athens in 480 BC, the town and acropolis were rebuilt, and theatre became formalized and an even greater part of Athenian culture and civic pride.

The center-piece of the annual Dionysia, which took place once in winter and once in spring, was a competition between three tragic playwrights at the Theatre of Dionysus.

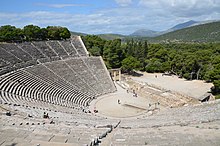

There were often tall, arched entrances called parodoi or eisodoi, through which actors and chorus members entered and exited the orchestra.

After 465 BC, playwrights began using a backdrop or scenic wall, called the skené (from which the word scene derives), that hung or stood behind the orchestra and also served as an area where actors could change their costumes.

[citation needed] Conversely, there are scholarly arguments that death in Greek tragedy was portrayed off stage primarily because of dramatic considerations, and not prudishness or sensitivity of the audience.

[18] No physical evidence remains available to us, as the masks were made of organic materials and not considered permanent objects, ultimately being dedicated at the altar of Dionysus after performances.

Stylized comedy and tragedy masks said to originate in ancient Greek theatre have come to widely symbolize the performing arts generally.

The masks were most likely made out of light weight, organic materials like stiffened linen, leather, wood, or cork, with the wig consisting of human or animal hair.

Vervain and Wiles posit that this small size discourages the idea that the mask functioned as a megaphone, as originally presented in the 1960s.

[18] Greek mask-maker Thanos Vovolis suggests that the mask serves as a resonator for the head, thus enhancing vocal acoustics and altering its quality.

Their variations help the audience to distinguish sex, age, and social status, in addition to revealing a change in a particular character's appearance, e.g., Oedipus, after blinding himself.

[25] Unique masks were also created for specific characters and events in a play, such as the Furies in Aeschylus' Eumenides and Pentheus and Cadmus in Euripides' The Bacchae.

Worn by the chorus, the masks created a sense of unity and uniformity, while representing a multi-voiced persona or single organism and simultaneously encouraged interdependency and a heightened sensitivity between each individual of the group.

The modern method to interpret a role by switching between a few simple characters goes back to changing masks in the theatre of ancient Greece.

Some examples of Greek theatre costuming include long robes called chiton that reached the floor for actors playing gods, heroes, and old men.