Theory and Construction of a Rational Heat Motor

Theory and Construction of a Rational Heat Motor (German: Theorie und Konstruktion eines rationellen Wärmemotors zum Ersatz der Dampfmaschine und der heute bekannten Verbrennungsmotoren; English: Theory and construction of a rational heat motor with the purpose of replacing the steam engine and the internal combustion engines known today) is an essay written by German engineer Rudolf Diesel.

[2] Diesel sent copies of his essay to famous German engineers and university professors for spreading and promoting his idea.

He received plenty of negative feedback; many considered letting Diesel's heat engine become reality unfeasible, because of the high pressures of 200–300 atm (20.3–30.4 MPa) occurring, which they thought machines of the time could not withstand.

In 1897, after four years of work, Diesel had successfully finished his rational heat motor using his modified combustion process.

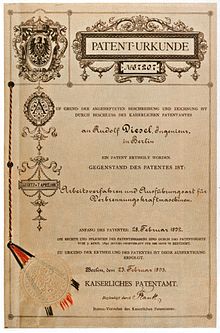

Publicly, Diesel never admitted that he had to use a different combustion process from that one he described in his essay, because this would have rendered his heat motor patent obsolete.

The fifth chapter addresses yet another modified process, with an incomplete expansion phase, but Diesel does not include a design concept.

His additional work Nachträge zur Bröschüre is not included in the original essay, but in newer editions, it serves as a tenth chapter.

[18] Diesel's theory had three major problems: The thermal efficiency and motor work do not depend on the amount of air, but on the compression ratio.

[23] His solution for the heat dissipation problem was still wrong: He decided to use more air, resulting in an air-fuel mixture which is too lean.

However, most critics did not criticise the theory's flaw, but that Diesel's heat engine used very high amounts of pressure to operate.

[5] Diesel himself acknowledged the feedback: Publishing my essay caused fierce reviews ... on average, they were unfavourable, rather devastating ...

[24][5] In his 1887 work Theorie der Gasmotoren, Otto Köhler had already addressed that an ideal cycle is not suitable for a real motor, coming to the same conclusion as the former.

(...) In my opinion, the entire indicated work of Diesel′s motor will be required to overcome the enormous friction.Other critics rather feared that the material would not withstand the enormous strain, but otherwise did not criticise the mistake of Diesel's theory: I hope you will not resent me, but having a lot of practical experience, I have serious doubts regarding the creation of an actual engine based on these theories.

I wish you that you will succeed ... bringing a well-engineered product to market, carefully made in silence, and dislodging the steam engine from its throne at the end of the century it assumed it!

Furthermore, the engineer will have a satisfying task purposely designing the new motor for industrial applications, both small and huge in their dimensions, as well as for locomotives and ships.

The high scientific, technical and economical importance of Diesel′s rational heat motor will sure boost its development...Your machine yet again attacks the mighty steam engine by outperforming it in its efficiency.

In a letter addressed to Moritz Schröter, dated 13 February 1893, Diesel describes the thermal efficiency of his rational heat motor, assuming maximum losses.

He started designing a new combustion process in May 1893 titled „Schlußfolgerungen über die definitiv f. d. Praxis zu wählende Arbeitsmethode des Motors“ (conclusion of the operating principle that definitely has to be chosen for a practical engine); it took until September the same year.

By 16 June 1893,[8] before he started the experiments with his engine at the Maschinenfabrik Augsburg, he had realised that the Carnot cycle is practically not possible and that he, therefore, has to change the way his motor works: ″Despite my older contrary statement, the question has to be answered, whether or not combustion processes other than the isothermal process would result in a bigger diagram″ (=actual engine work).

[25] To achieve this, Diesel now wanted to raise point 3 in his diagram instead of increasing the length of the admission period 2–3 by reducing injection time.

[31] When reducing the compression pressure, Diesel always tried keeping it above the self-ignition temperature of the fuel, which is why he eventually decided to choose 30 atm.