Real analysis

[1] Some particular properties of real-valued sequences and functions that real analysis studies include convergence, limits, continuity, smoothness, differentiability and integrability.

[2] The domain is usually taken to be the natural numbers,[3] although it is occasionally convenient to also consider bidirectional sequences indexed by the set of all integers, including negative indices.

Of interest in real analysis, a real-valued sequence, here indexed by the natural numbers, is a map

when addressing the behavior of a function or sequence as the variable increases or decreases without bound.)

The idea of a limit is fundamental to calculus (and mathematical analysis in general) and its formal definition is used in turn to define notions like continuity, derivatives, and integrals.

The concept of limit was informally introduced for functions by Newton and Leibniz, at the end of the 17th century, for building infinitesimal calculus.

For sequences, the concept was introduced by Cauchy, and made rigorous, at the end of the 19th century by Bolzano and Weierstrass, who gave the modern ε-δ definition, which follows.

In a slightly different but related context, the concept of a limit applies to the behavior of a sequence

Generalizing to a real-valued function of a real variable, a slight modification of this definition (replacement of sequence

The distinction between pointwise and uniform convergence is important when exchanging the order of two limiting operations (e.g., taking a limit, a derivative, or integral) is desired: in order for the exchange to be well-behaved, many theorems of real analysis call for uniform convergence.

Karl Weierstrass is generally credited for clearly defining the concept of uniform convergence and fully investigating its implications.

Compactness is a concept from general topology that plays an important role in many of the theorems of real analysis.

(In the context of real analysis, these notions are equivalent: a set in Euclidean space is compact if and only if it is closed and bounded.)

, a set is subsequentially compact if and only if it is closed and bounded, making this definition equivalent to the one given above.

A function from the set of real numbers to the real numbers can be represented by a graph in the Cartesian plane; such a function is continuous if, roughly speaking, the graph is a single unbroken curve with no "holes" or "jumps".

This somewhat unintuitive treatment of isolated points is necessary to ensure that our definition of continuity for functions on the real line is consistent with the most general definition of continuity for maps between topological spaces (which includes metric spaces and

Absolute continuity is a fundamental concept in the Lebesgue theory of integration, allowing the formulation of a generalized version of the fundamental theorem of calculus that applies to the Lebesgue integral.

A series formalizes the imprecise notion of taking the sum of an endless sequence of numbers.

The idea that taking the sum of an "infinite" number of terms can lead to a finite result was counterintuitive to the ancient Greeks and led to the formulation of a number of paradoxes by Zeno and other philosophers.

" is merely a notational convention to indicate that the partial sums of the series grow without bound.)

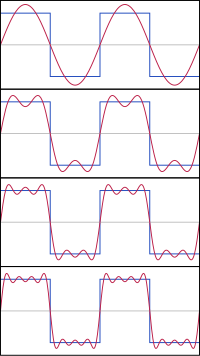

Fourier series decomposes periodic functions or periodic signals into the sum of a (possibly infinite) set of simple oscillating functions, namely sines and cosines (or complex exponentials).

The basic strategy to solving problems of this type was known to the ancient Greeks and Chinese, and was known as the method of exhaustion.

By considering approximations consisting of a larger and larger ("infinite") number of smaller and smaller ("infinitesimal") pieces, the area bound by the curve can be deduced, as the upper and lower bounds defined by the approximations converge around a common value.

The spirit of this basic strategy can easily be seen in the definition of the Riemann integral, in which the integral is said to exist if upper and lower Riemann (or Darboux) sums converge to a common value as thinner and thinner rectangular slices ("refinements") are considered.

The fundamental theorem of calculus asserts that integration and differentiation are inverse operations in a certain sense.

The concept of a measure, an abstraction of length, area, or volume, is central to Lebesgue integral probability theory.

Distributions make it possible to differentiate functions whose derivatives do not exist in the classical sense.

However, results such as the fundamental theorem of algebra are simpler when expressed in terms of complex numbers.

Investigation of the consequences of generalizing differentiability from functions of a real variable to ones of a complex variable gave rise to the concept of holomorphic functions and the inception of complex analysis as another distinct subdiscipline of analysis.

Finally, the generalization of integration from the real line to curves and surfaces in higher dimensional space brought about the study of vector calculus, whose further generalization and formalization played an important role in the evolution of the concepts of differential forms and smooth (differentiable) manifolds in differential geometry and other closely related areas of geometry and topology.