Somatic cell nuclear transfer

[2] "Therapeutic cloning" refers to the potential use of SCNT in regenerative medicine; this approach has been championed as an answer to the many issues concerning embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and the destruction of viable embryos for medical use, though questions remain on how homologous the two cell types truly are.

[4] Although Dolly is generally recognized as the first animal to be cloned using this technique, earlier instances of SCNT exist as early as the 1950s.

In particular, the research of Sir John Gurdon in 1958 entailed the cloning of Xenopus laevis utilizing the principles of SCNT.

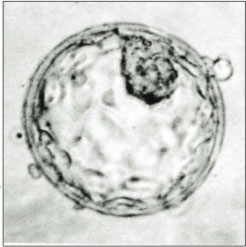

[9] Using the micromanipulator, a scientist makes an opening in the zona pellucida and sucks out the egg cell's original nucleus using a pipette.

This gives them the ability to create patient specific pluripotent cells, which could then be used in therapies or disease research.

These cells are deemed to have a pluripotent potential because they have the ability to give rise to all of the tissues found in an adult organism.

The disease specific stem cell lines could then be studied in order to better understand the condition.

[18] In the United Kingdom, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority has granted permission to research groups at the Roslin Institute and the Newcastle Centre for Life.

Despite many attempts, success in creating human nuclear transfer embryonic stem cells has been limited.

A research group from the Oregon Health & Science University demonstrated SCNT procedures developed for primates successfully using skin cells.

It is theorized the critical embryonic genes are physically linked to oocyte chromosomes, enucleation negatively affects these factors.

Taking this into account the research group applied their new technique in an attempt to produce human SCNT stem cells.

Using MII oocytes from volunteers and their improved SCNT procedure, human clone embryos were successfully produced.

The addition of caffeine during the removal of the ovum's nucleus and fusion of the somatic cell and the egg improved blastocyst formation and ESC isolation.

Epigenetic and age related changes were thought to possibly hinder an adult somatic cells ability to be reprogrammed.

[25] Recent studies indicate however that changes to the epigenetic memory of iPSCs using small molecules can reset them to an almost naive state of pluripotency.

[26][27] Studies have even shown that via tetraploid complementation, an entire viable organism can be created solely from iPSCs.

The cause for low yields in bovine SCNT cloning has, in recent years, been attributed to the previously hidden epigenetic memory of the somatic cells that were being introduced into the oocyte.

It remains a possibility, though critical adjustments will be required to overcome current limitations during early embryonic development in human SCNT.

Interspecies nuclear transfer utilizes a host and a donor of two different organisms that are closely related species and within the same genus.

For example, in 1996 Dolly the sheep was born after 277 eggs were used for SCNT, which created 29 viable embryos, giving it a measly 0.3% efficiency.

[40] The biochemistry involved in reprogramming the differentiated somatic cell nucleus and activating the recipient egg was also far from understood.

The biochemistry also has to be extremely precise, as most late term cloned fetus deaths are the result of inadequate placentation.

This fact may also hamper the potential benefits of SCNT-derived tissues and organs for therapy, as there may be an immuno-response to the non-self mtDNA after transplant.

Differing regulation of these histone methylation genes can directly affect the transcription of the developing genome, causing failure of the SCNT.

Those who hold this concern often advocate for strong regulation of SCNT to preclude implantation of any derived products for the intention of human reproduction,[49] or its prohibition.

Stem cell experts consider it unlikely that such large numbers of human egg donations would occur in a developed country because of the unknown long-term public health effects of treating large numbers of healthy young women with heavy doses of hormones in order to induce hyper-ovulation (ovulating several eggs at once).

Although such treatments have been performed for several decades now, the long-term effects have not been studied or declared safe to use on a large scale on otherwise healthy women.

If successful, human egg donations would not be needed to create custom stem cell lines.

[50][7] Permission must be obtained from the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority in order to perform or attempt SCNT.