Thermochemical cycle

In chemistry, thermochemical cycles combine solely heat sources (thermo) with chemical reactions to split water into its hydrogen and oxygen components.

This concept was first postulated by Funk and Reinstrom (1966) as a maximally efficient way to produce fuels (e.g. hydrogen, ammonia) from stable and abundant species (e.g. water, nitrogen) and heat sources.

Hence, a mobile production system based on a portable heat source (a nuclear reactor was considered) was being investigated with utmost interest.

Following the oil crisis, multiple programs (Europe, Japan, United States) were created to design, test and qualify such processes for purposes such as energy independence.

However, optimistic expectations based on initial thermodynamics studies were quickly moderated by pragmatic analyses comparing standard technologies (thermodynamic cycles for electricity generation, coupled with the electrolysis of water) and by numerous practical issues (insufficient temperatures from even nuclear reactors, slow reactivities, reactor corrosion, significant losses of intermediate compounds with time...).

[3] Hence, the interest for this technology faded during the next decades,[4] or at least some tradeoffs (hybrid versions) were being considered with the use of electricity as a fractional energy input instead of only heat for the reactions (e.g.

A rebirth in the year 2000 can be explained by both the new energy crisis, demand for electricity, and the rapid pace of development of concentrated solar power technologies whose potentially very high temperatures are ideal for thermochemical processes,[5] while the environmentally friendly side of thermochemical cycles attracted funding in a period concerned with a potential peak oil outcome.

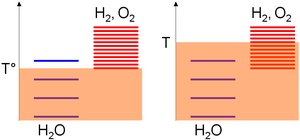

Relative to the absolute temperature scale, the excitation levels of the species are gathered based on standard enthalpy change of formation considerations; i.e. their stabilities.

This equation can alternatively (and naturally) be derived via the Carnot's theorem, that must be respected by the system composed of a thermochemical process coupled with a work producing unit (chemical species are thus in a closed loop): Consequently, replacing W (ΔG°) and Q (Eq.

(15) becomes after reorganization, Using a work input equals to a fraction f of the heat input is equivalent relative to the choice of the reactions to operate a pure similar thermochemical cycle but with a hot source with a temperature increased by the same proportion f. Naturally, this decreases the heat-to-work efficiency in the same proportion f. Consequently, if one want a process similar to a thermochemical cycle operating with a 2000K heat source (instead of 1000K), the maximum heat-to-work efficiency is twice lower.

As an example in Europe, this is the goal of the Hydrosol-2 project (Greece, Germany (German Aerospace Center), Spain, Denmark, England) [9] and of the researches of the solar department of the ETH Zurich and the Paul Scherrer Institute (Switzerland).

Furthermore, assuming similar stabilities of the reactant (ΔH°) for both thermolysis and oxide dissociation, a larger entropy change in the second case explained again a lower reaction temperature (Eq.(3)).

An extra property can be derived in order to have TH strictly lower than the thermolysis temperature: The standard thermodynamic values must be unevenly distributed among the reactions .

[13] Two-step thermochemical cycles, often involving metal oxides,[14] can be divided into two categories depending on the nature of the reaction: volatile and non-volatile.

[16] Due to sulfur's high covalence, it can form up to 6 chemical bonds with other elements such as oxygen, resulting in a large number of oxidation states.

Much of the initial research was conducted in the United States, with sulfate- and sulfide-based cycles studied at Kentucky University,[17][18] the Los Alamos National Laboratory[19] and General Atomics.