Thermoelectric generator

[2] When the same principle is used in reverse to create a heat gradient from an electric current, it is called a thermoelectric (or Peltier) cooler.

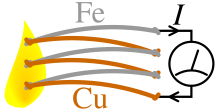

[3][4] In 1821, Thomas Johann Seebeck discovered that a thermal gradient formed between two different conductors can produce electricity.

These are solid-state devices and unlike dynamos have no moving parts, with the occasional exception of a fan or pump to improve heat transfer.

[16] Thermoelectric materials generate power directly from the heat by converting temperature differences into electric voltage.

[citation needed] Today, the thermal conductivity of semiconductors can be lowered without affecting their high electrical properties using nanotechnology.

Thermoelectric generators are all-solid-state devices that do not require any fluids for fuel or cooling, making them non-orientation dependent allowing for use in zero-gravity or deep-sea applications.

Thermoelectric generators have no moving parts which produce a more reliable device that does not require maintenance for long periods.

The durability and environmental stability have made thermoelectrics a favorite for NASA's deep space explorers among other applications.

[18] One of the key advantages of thermoelectric generators outside of such specialized applications is that they can potentially be integrated into existing technologies to boost efficiency and reduce environmental impact by producing usable power from waste heat.

Because they operate in a very high-temperature gradient, the modules are subject to large thermally induced stresses and strains for long periods.

[20] For microelectromechanical systems, TEGs can be designed on the scale of handheld devices to use body heat in the form of thin films.

Cylindrical TEGs for using heat from vehicle exhaust pipes can also be made using circular thermocouples arranged in a cylinder.

Achieving high efficiency in the system requires extensive engineering design to balance between the heat flow through the modules and maximizing the temperature gradient across them.

Thermal expansion will then introduce stress in the device which may cause fracture of the thermoelectric legs or separation from the coupling material.

Recent research has focused on improving the material’s figure-of-merit (zT), and hence the conversion efficiency, by reducing the lattice thermal conductivity.

One example of these materials is the semiconductor compound ß-Zn4Sb3, which possesses an exceptionally low thermal conductivity and exhibits a maximum zT of 1.3 at a temperature of 670K.

For example, the rare earth compounds YbAl3 has a low figure-of-merit, but it has a power output of at least double that of any other material, and can operate over the temperature range of a waste heat source.

[28] In a bismuth antimony tellurium ternary system, liquid-phase sintering is used to produce low-energy semicoherent grain boundaries, which do not have a significant scattering effect on electrons.

[30] These improvements highlight the fact that in addition to the development of novel materials for thermoelectric applications, using different processing techniques to design microstructure is a viable and worthwhile effort.

The thermal to electric energy conversion can be performed using components that require no maintenance, have inherently high reliability, and can be used to construct generators with long service-free lifetimes.

This makes thermoelectric generators well suited for equipment with low to modest power needs in remote uninhabited or inaccessible locations such as mountaintops, the vacuum of space, or the deep ocean.

A simple approach to generate the necessary temperature gradient across the TEGs is to apply heat sinks to promote convective cooling.

The higher-wavelength infrared spectrum is diverted to an array of TEGs where the thermal energy is scavenged for electricity generation.

On research group placed a PV-TEG system in an evacuated chamber to prevent convection on the top (hot) surface of the PV array, and to allow them to more carefully control the temperature gradient across the TEGs.

These materials can help maintain a constant cold-side temperature over the entire panel area and avoid hot spots that may reduce PV efficiency.

Until TEGs can produce higher than single-digit efficiencies under typical temperature gradients in ambient conditions, they will remain on the fringe of commercial development.

The added cost of including TEG arrays on solar panels cannot be justified for the marginal efficiency gains seen with current materials and architectures.

While TEG technology has been used in military and aerospace applications for decades, new TE materials[48] and systems are being developed to generate power using low or high temperatures waste heat, and that could provide a significant opportunity in the near future.

Recent studies focused on the novel development of a flexible inorganic thermoelectric, silver selenide, on a nylon substrate.

Thermoelectrics represent particular synergy with wearables by harvesting energy directly from the human body creating a self-powered device.