Thiamine

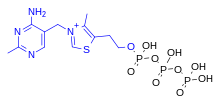

[1] Phosphorylated forms of thiamine are required for some metabolic reactions, including the breakdown of glucose and amino acids.

[13] Oxidation yields the fluorescent derivative thiochrome, which can be used to determine the amount of the vitamin present in biological samples.

[3] The mitochondrial PDH and OGDH are part of biochemical pathways that result in the generation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is the main energy transfer molecule for the cell.

[1][3] Pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum are at an increased risk of thiamine deficiency due to losses when vomiting.

[23] The US National Academy of Medicine updated the Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for thiamine in 1998.

For women (including those pregnant or lactating), men and children the PRI is 0.1 mg thiamine per megajoule (MJ) of energy in their diet.

[33] Neither the National Academy of Medicine nor EFSA have set an upper intake level for thiamine, as there is no human data for adverse effects from high doses.

[6] There are rare reports of adverse side effects when thiamine is given intravenously, including allergic reactions, nausea, lethargy, and impaired coordination.

[32][11] For US food and dietary supplement labeling purposes, the amount in a serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value.

[1][34][35] Thiamine is found in a wide variety of processed and whole foods, including lentils, peas, whole grains, pork, and nuts.

[37] Some countries require or recommend fortification of grain foods such as wheat, rice or maize (corn) because processing lowers vitamin content.

The pyrimidine ring system is formed in a reaction catalysed by phosphomethylpyrimidine synthase (ThiC), an enzyme in the radical SAM superfamily of iron–sulfur proteins, which use S-adenosyl methionine as a cofactor.

[43][44] The starting material is 5-aminoimidazole ribotide, which undergoes a rearrangement reaction via radical intermediates which incorporate the blue, green and red fragments shown into the product.

[51] However, an alternative route using the intermediate Grewe diamine (5-(aminomethyl)-2-methyl-4-pyrimidinamine), first published in 1937,[52] was investigated by Hoffman La Roche and competitive manufacturing processes followed.

[51][53] In the European Economic Area, thiamine is registered under REACH regulation and between 100 and 1,000 tonnes per annum are manufactured or imported there.

[56][57][58] In the upper small intestine, thiamine phosphate esters present in food are hydrolyzed by alkaline phosphatase enzymes.

[17] Human storage of thiamine is about 25 to 50 mg,[1][62] with the greatest concentrations in liver,[1][63] skeletal muscle, heart, brain, and kidneys.

[5] Additionally, thiamine pyrophosphate derived from pyrimidines supports lipid synthesis and adipogenesis, highlighting its role in energy storage and cellular differentiation.

[72] The earliest observations in humans and in chickens had shown that diets of primarily polished white rice caused beriberi, but did not attribute it to the absence of a previously unknown essential nutrient.

[73][74] In 1884, Takaki Kanehiro, a surgeon general in the Imperial Japanese Navy, rejected the previous germ theory for beriberi and suggested instead that the disease was due to insufficiencies in the diet.

However, Takaki had added many foods to the successful diet and he incorrectly attributed the benefit to increased protein intake, as vitamins were unknown at the time.

The Navy was not convinced of the need for such an expensive program of dietary improvement, and many men continued to die of beriberi, even during the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–5.

[76] Eijkman was eventually awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1929, because his observations led to the discovery of vitamins.

In 1910, a Japanese agricultural chemist of Tokyo Imperial University, Umetaro Suzuki, isolated a water-soluble thiamine compound from rice bran, which he named aberic acid.

[72] In 1911 a Polish biochemist Casimir Funk isolated the antineuritic substance from rice bran (the modern thiamine) that he called a "vitamine" (on account of its containing an amino group).

Dutch chemists, Barend Coenraad Petrus Jansen and his closest collaborator Willem Frederik Donath, went on to isolate and crystallize the active agent in 1926,[79] whose structure was determined by Robert Runnels Williams, in 1934.

[80] Sir Rudolph Peters, in Oxford, used pigeons to understand how thiamine deficiency results in the pathological-physiological symptoms of beriberi.

Pigeons fed exclusively on polished rice developed opisthotonos, a condition characterized by head retraction.

As no morphological modifications were seen in the brain of the pigeons before and after treatment with thiamine, Peters introduced the concept of a biochemical-induced injury.

[81] In 1937, Lohmann and Schuster showed that the diphosphorylated thiamine derivative, TPP, was a cofactor required for the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate.