Thorfinn the Mighty

However, two pieces of circumstantial evidence may well point to a death date of around 1058: firstly, that in that year, King Harald's elder son Magnus Haraldsson (the future King Magnus II) led an expedition to Orkney and the Isles, which is speculated to have been an effort to restore order there following Thorfinn's death - at which point, his sons Paul and Erlend, would have been minors.

The Heimskringla of Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson, and the anonymous compiler of the Orkneyinga Saga wrote that Thorfinn was the most powerful of all the jarls of Orkney and that he ruled substantial territories beyond the Northern Isles.

His elder half-brothers Einar, Brusi and Sumarlidi survived to adulthood, while another brother called Hundi died young in Norway, a hostage at the court of King Olaf Trygvasson.

[Note 3] Sumarlidi died in his bed not long after his father, most likely no later than 1018[17] and Einar took his share, ruling two-thirds of the earldom with the remaining third held by Brusi.

[18] The farmers of the isles opposition to Einar's rule were led by Thorkel Amundason and, in danger of his life, he fled to Thorfinn's court in Caithness.

On the last day of the feast Thorkel was supposed to travel with Einar for the reciprocal event, however his spies reported to him that ambushes had been prepared against him along his route.

However, Thorfinn could count on the assistance of his grandfather, King Malcolm, while Brusi had only the forces he could raise from his share of the islands, making any conflict a very unequal one.

The Orkneyinga Saga says that a dispute between Thorfinn and Karl Hundason began when the latter became "King of Scots" and claimed Caithness, his forces successfully moving north and basing themselves in Thurso.

Finally, a great battle at "Torfness" (probably Tarbat Ness on the south side of the Dornoch Firth[32]) ended with Karl either being killed or forced to flee.

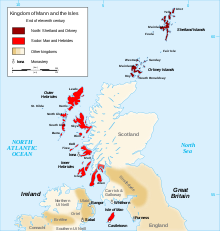

[33] At some point around 1034 Thorfinn is said to have conquered the Hebrides and he is likely to have been a de facto ruler of the Kingdom of the Isles, in whole or in part until his death[11] (although the assumption of Echmarcach mac Ragnaill as "King of Mann" from 1052 to 1061 may have encroached on his territories).

Rognvald had received the favour of King Magnus "the Good" Olafsson, who granted him Brusi's share of the islands and the third which Olaf Haraldsson had claimed after Einar's death.

They are said to have won a major victory beside Vatzfjorðr, perhaps Loch Vatten on the west coast of Skye,[39][40][Note 5] and to have raided in England, with mixed success.

[45] Thorfinn found hosting Kalf and his men a burden, and in time asked Rognvald to return the third of the earldom "which had once belonged to Einar Wry-Mouth".

The saga recounts an attempt to make peace with Magnus Olafsson, who had sworn vengeance for the death of his men in Thorfinn's attack on Rognvald.

[50][53][54] The Orkneyinga saga dates Thorfinn's death no more precisely than placing it "towards the end" of Harald Sigurdsson's reign, who died at the battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066.

He is known to history as "Thorfinn the Mighty", and at his height of power, he controlled all of Orkney and Shetland, the Hebrides, Caithness and Sutherland, and his influence extended over much of the north of Scotland.

There are also a number of parallels with the life of Harald Maddadsson[5] and Woolf (2007) speculates that aspects of Thorfinn's story may have been included to legitimise the latter's adventures.

Woolf (2007) suggests that the reference may then be to Máel Coluim mac Máil Brigti a Pictish Mormaer of Moray or alternatively that, as elsewhere in Icelandic literature, Melkólmr was simply used as a generic name, in this case for Scottish royalty.

[76] Muir (2005) points out that a literal translation of "Karl Hundisson" is "peasant son-of-a-dog", an insult that would have been obvious to Norse-speakers hearing the saga and that "we can assume this wasn't his real name".

Thomson (2008) notes that the war with Hundasson seem to have taken place between 1029 and 1035 and that the Annals of Ulster record the violent death of Gillacomgain, brother of Máel Coluim mac Máil Brigti and Mormaer of Moray, in 1032.

He too is thus a candidate for Thorfinn's Scots foe—and the manner of his death by fire bears comparison with Arnór's poetic description of the aftermath of the battle at Torfness.

[83] In this case the Sigurdsson brothers do not assassinate one another, but rather Thorkel Fosterer becomes an intermediary, killing both Einar rangmunnr and, at a later date, Rögnvald Brusasson on behalf of Thorfinn.

[25][84] It is also clear that there is a moral element to the tale, with Brusi cast as the peacemaker who is father to the noble Rögnvald and who stands in contrast to his greedy half-brother.

The Norse in the Northern Isles would have been strongly influenced by the neighbouring Christian countries and it is likely that marriages to individuals from such polities would have required baptism even before his time.

Informal pagan practice was likely conducted throughout his earldom,[85] but the weight of archaeological evidence suggests that Christian burial was widespread in Orkney even during the reign of Sigurd Hlodvirsson, Thorfinn's father.

Crawford (1987) observes several sub-themes: "submission and of overlordship; the problem of dual allegiance and the threat of the earls looking to the kings of Scots as an alternative source of support; the Norwegian kings' use of hostages; and their general aim of attempting to turn the Orkney earls into royal officials bound to them by oaths of homage, and returning tribute to them on a regular basis.

"[91] King Olaf was a "skilled practitioner" of divide and rule and the competing claims of Brusi and Thorfinn enabled him to take full advantage.

[91] Although Thorfinn is clearly stated to be fighting in and around Fife[93] Thomson (2008) suggests that his presence so far south may have been as an ally of his grandfather rather than at the head of an invading army.

[87][Note 13] Finally, Thorfinn's death may have created a power vacuum and been a cause of the invasion of the Irish Sea region nominally led by King Harald harðraði's young son Magnus Haraldsson dated to 1058.

[8] The basis of Dorothy Dunnett's 1982 novel King Hereafter is a point made by W. F. Skene, who noted that the historical sources which mention Thorfinn do not refer to MacBeth, and vice versa.