Timothy L. Pflueger

[2] Together with James R. Miller, Pflueger designed some of the leading skyscrapers and movie theaters in San Francisco in the 1920s,[3] and his works featured art by challenging new artists such as Ralph Stackpole and Diego Rivera.

Pflueger, who started as a working-class draftsman and never went to college, established his imprint on the development of Art Deco in California architecture yet demonstrated facility in many styles including Streamline Moderne, neo-Mayan,[5] Beaux-Arts, Mission Revival, Neoclassical and International.

[8] After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, Pflueger continued his grade-school education, graduating at age 13 in a mass ceremony held in Golden Gate Park for all the city's devastated public schools.

Subsequently, Pflueger was assigned by Miller to work closely with the firm's major client, Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, who engaged in a succession of expansion projects at their San Francisco location at 600 Stockton Street.

[1] J. R. Miller, relying more and more on Pflueger's hard-working energy, social conviviality and artistic talent, gave him a wide variety of assignments including designs for an automobile showroom, a firehouse and a number of private homes.

In June 1924, Pflueger showed his plans for a $3 million skyscraper, 26 stories high, designed with continuous vertical elements and a progression of step-backs narrowing the floors near the top.

[1] 450 Sutter Street was completed on October 15, 1929, using a primarily unbroken exterior verticality without step-backs, featuring triangular thrust window bays, the whole decorated with stylized Mayan designs impressed on the terra cotta sheathing and inscribed in metals, marble and glass within the luxurious lobby.

[1] By the late 1920s, Pflueger was already working with a number of artists such as Haig Patigian, Jo Mora and Arthur Mathews who provided fine detail and craftsmanship to his larger designs.

In March 1928, Pflueger published his submission for a new building to house the San Francisco Stock Exchange, featuring strong Zigzag Moderne themes with classicist notes.

Eight months later, the Exchange committee decided instead to rebuild the Sub-treasury building at 301 Pine Street while keeping its Tuscan columns and entrance steps, requiring a completely new approach.

A canopy modeled after ancient Roman silk brocade shelters was fashioned of steel lath and plaster and painted with Asian and Buddha figures to overhang the main theater seating area.

Pflueger's vision stayed firmly planted in the Moorish Revival style, complete to the iron scrollwork and amber shade redesign of two municipal streetlamps standing outside of the theater.

Pflueger worked with muralist Arthur Frank Mathews to achieve a rich palette of color most prominently displayed in a geometric floral pattern on the main ceiling.

Pflueger included zigzag patterns in the twin-towered facade trimmed in neon accents, and brought Streamline Moderne stylings to the interior via sweeping curves in steel banister railings as well as Mayan touches in the stepped mirrors.

The $250,000 State Theatre appeared Spanish Colonial with its tiled roof and concrete bas-relief exterior, but turned to Streamline Moderne in a 1,529-seat[20] interior that featured chrome railings, plush carpet and indirect lighting.

The movie palace's eclectic theme was largely Egyptian[21] with Moorish, Asian and Aztec details dominated by a landmark tower topped by a giant faceted amber glass gem lit from within.

[1] Back in San Francisco, Pflueger designed the Nasser Brothers' 1,830-seat El Rey Theatre (1931) at 1970 Ocean Avenue[22] in pure Moderne style, including a sleek tower topped by an aircraft warning beacon.

[1] Shortly before the Wall Street Crash of 1929, investors including William Henry Crocker bought adjoining parcels of land in Oakland for the purpose of erecting a movie palace to rival the nearby Fox Orpheum, intending that Miller and Pflueger build it.

Pflueger went to New York and convinced Paramount Publix to use his firm by demonstrating that past projects of his had stayed within budget, a concern of increasing importance in the cautious financial climate of early 1930.

[25] In the interest of economy, the Alameda's floor plan was nearly identical to that of the El Rey Theatre, including twin curved staircases, and some floral and geometric elements were borrowed from the Paramount.

[31] Pflueger was invited by California governor James "Sunny Jim" Rolph to chair the committee of architects who were given nominal oversight of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge project.

A heroic figure of a giant man standing at the central anchorage between the two main suspension spans was suggested and quickly canceled; all that remains of the proposal is a 14-inch study modeled by Ralph Stackpole.

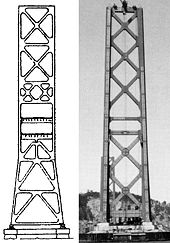

The committee of architects succeeded mainly in making the suspension bridge towers more streamlined in appearance by getting rid of the civil engineer's plans for a greater number of horizontal cross members.

[1][32] For the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939–1940 on Treasure Island, Pflueger joined a committee of well-known Beaux-Arts architects and was frustrated in establishing a more modern design scheme,[5] though his own Federal Building amply demonstrated the new direction he espoused.

Pflueger's interior was attuned to women's fashions: the ground level floor was laid with rose-beige marble from France, pink velvet counter tops held gloves for trying on, rose-beige leather panels covered the walls of the shoe salon and the same leather served as covering for sofas and chairs that were provided by Neel D. Parker, interior designer and Pflueger's fellow club member from The Family.

George Applegarth's 1935 design was actively opposed from several directions and Pflueger's social contacts and his friendship with mayor Angelo Joseph Rossi were needed to get the project moving.

The concept of an underground garage below a city park was influential: New York builder Robert Moses requested copies of Pflueger's plans (little changed from Applegarth's) and Pershing Square in Los Angeles was excavated and rebuilt in 1952 along the same lines.

He began to draw up plans for a 12-story cross-shaped medical teaching hospital for the University of California, San Francisco (eventually to be built at 505 Parnassus in 1955 with additional design work performed by his brother Milton Pflueger).

His firm accepted a commission to excavate below the Mark Hopkins Hotel in order to create a bomb-resistant radio transmission center for AM station KSFO and shortwave programs of the Voice of America.

[1] At his death, Pflueger was not finished with the radical interior and exterior transformation of the I. Magnin flagship store at Union Square, a sleek International design that remained influential for years afterward.