Polar vortex

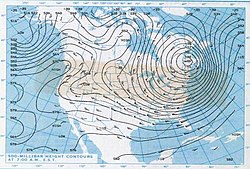

The stratospheric and tropospheric polar vortices both rotate in the direction of the Earth's spin, but they are distinct phenomena that have different sizes, structures, seasonal cycles, and impacts on weather.

The tropospheric vortex increased in public visibility in 2021 as a result of extreme frigid temperatures in the central United States, with newspapers linking its effects to climate change.

When this northern tropospheric vortex weakens, it breaks into two or more smaller vortices, the strongest of which are near Baffin Island, Nunavut, and the others over northeast Siberia.

The US National Weather Service warned that frostbite is possible within just 10 minutes of being outside in such extreme temperatures, and hundreds of schools, colleges, and universities in the affected areas were closed.

[9] The Antarctic vortex of the Southern Hemisphere is a single low-pressure zone that is found near the edge of the Ross ice shelf, near 160 west longitude.

When the polar vortex is strong, the mid-latitude Westerlies (winds at the surface level between 30° and 60° latitude from the west) increase in strength and are persistent.

[10] In Australia, the polar vortex, known there as a "polar blast" or "polar plunge", is a cold front that drags air from Antarctica which brings rain showers, snow (typically inland, with blizzards occurring in the highlands), gusty icy winds, and hail in the south-eastern parts of the country, such as in Victoria, Tasmania, the southeast coast of South Australia and the southern half of New South Wales (but only on the windward side of the Great Dividing Range, whereas the leeward side will be affected by foehn winds).

This event signifies the transition from winter to spring, and has impacts on the hydrological cycle, growing seasons of vegetation, and overall ecosystem productivity.

Early and late polar breakup episodes have occurred, due to variations in the stratospheric flow structure and upward spreading of planetary waves from the troposphere.

Scientists are connecting a delay in the Arctic vortex breakup with a reduction of planetary wave activities, few stratospheric sudden warming events, and depletion of ozone.

A soft spot just south of Greenland is where the initial step of downwelling occurs, nicknamed the "Achilles Heel of the North Atlantic".

The planetary wave activity in both hemispheres varies year-to-year, producing a corresponding response in the strength and temperature of the polar vortex.

[34] Occasionally, the high-pressure air mass, called the Greenland Block, can cause the polar vortex to divert to the south, rather than follow its normal path over the North Atlantic.

[36] In the same year, researchers found a statistical correlation between weak polar vortex and outbreaks of severe cold in the Northern Hemisphere.

[43][44] While the Arctic remains one of the coldest places on Earth today, the temperature gradient between it and the warmer parts of the globe will continue to diminish with every decade of global warming as the result of this amplification.

If this gradient has a strong influence on the jet stream, then it will eventually become weaker and more variable in its course, which would allow more cold air from the polar vortex to leak mid-latitudes and slow the progression of Rossby waves, leading to more persistent and more extreme weather.

[45] While some paleoclimate reconstructions have suggested that the polar vortex becomes more variable and causes more unstable weather during periods of warming back in 1997,[46] this was contradicted by climate modelling, with PMIP2 simulations finding in 2010 that the Arctic Oscillation (AO) was much weaker and more negative during the Last Glacial Maximum, and suggesting that warmer periods have stronger positive phase AO, and thus less frequent leaks of the polar vortex air.

[52] At the time, it was also suggested that this connection between Arctic amplification and jet stream patterns was involved in the formation of Hurricane Sandy[53] and played a role in the early 2014 North American cold wave.

Hence, continued heat-trapping emissions favour increased formation of extreme events caused by prolonged weather conditions.

[57][58] Further work from Francis and Vavrus that year suggested that amplified Arctic warming is observed as stronger in lower atmospheric areas because the expanding process of warmer air increases pressure levels which decreases poleward geopotential height gradients.

[59] In 2017, Francis explained her findings to the Scientific American: "A lot more water vapor is being transported northward by big swings in the jet stream.

[62] Another 2017 paper estimated that when the Arctic experiences anomalous warming, primary production in North America goes down by between 1% and 4% on average, with some states suffering up to 20% losses.

[64][65] Another 2021 study identified a connection between the Arctic sea ice loss and the increased size of wildfires in the Western United States.

Climatology observations require several decades to definitively distinguish various forms of natural variability from climate trends.

[69] A study in 2014 concluded that Arctic amplification significantly decreased cold-season temperature variability over the northern hemisphere in recent decades.

[70] A 2019 analysis of a data set collected from 35 182 weather stations worldwide, including 9116 whose records go beyond 50 years, found a sharp decrease in northern midlatitude cold waves since the 1980s.

[71] Moreover, a range of long-term observational data collected during the 2010s and published in 2020 suggests that the intensification of Arctic amplification since the early 2010s was not linked to significant changes on mid-latitude atmospheric patterns.

[74][75] In 2022, a follow-up study found that while the PAMIP average had likely underestimated the weakening caused by sea ice decline by 1.2 to 3 times, even the corrected connection still amounts to only 10% of the jet stream's natural variability.

[80] The nitric acid in polar stratospheric clouds reacts with chlorofluorocarbons to form chlorine, which catalyzes the photochemical destruction of ozone.

[81] Chlorine concentrations build up during the polar winter, and the consequent ozone destruction is greatest when the sunlight returns in spring.