Tláloc

[7] The Mexican marigold, Tagetes lucida, known to the Nahua as cempohualxochitl, was another important symbol of the god, and was burned as a ritual incense in native religious ceremonies.

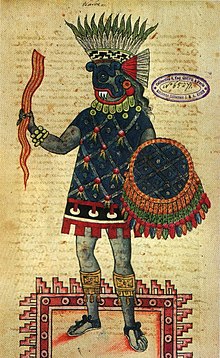

Representations of Tláloc are distinguished by the presence of fangs, whether that be three or four of the same size, or just two, paired with the traditional bifurcated tongue.

[8] Although the name Tláloc is specifically Nahuatl, worship of a storm god, associated with mountaintop shrines and with life-giving rain, is as at least as old as Teotihuacan.

Despite the fact that it has been half a millennium since the conquest of Mexico, Tláloc still plays a role in shaping Mexican culture.

[14] Tláloc and other pre-Hispanic features are critical to creating a common Mexican identity that unites people throughout Mexico.

Due to the fact that many scholars believe that Tláloc also has Mayan roots, this widespread appreciation is common in Mesoamerica.

[16] A chacmool excavated from the Maya site of Chichén Itzá in the Yucatán by Augustus Le Plongeon possesses imagery associated with Tláloc.

In addition to the chacmools, human corpses were found in close proximity to the Tlálocan half of Templo Mayor, which were likely war captives.

[18] Furthermore, Tláloc can be seen in many examples of Maya war imagery and war-time decoration, such as appearing on “shields, masks, and headdresses of warriors.”[19] This evidence affirms the Maya triple connection between war-time, sacrifice, and the rain deity as they likely adopted the rain deity from the Aztecs, but blurred the line between sacrifice and captive capture, and religion.

[20] In Aztec cosmology, the four corners of the universe are marked by "the four Tlálocs" (Classical Nahuatl: Tlālōquê [tɬaːˈloːkeʔ]) which both hold up the sky and function as the frame for the passing of time.

Described as a place of unending springtime and a paradise of green plants, Tlálocan was the destination in the afterlife for those who died violently from phenomena associated with water, such as by lightning, drowning, and water-borne diseases.

[16] These violent deaths also included leprosy, venereal disease, sores, dropsy, scabies, gout, and child sacrifices.

[10] The Nahua believed that Huitzilopochtli could provide them with fair weather for their crops and they placed an image of Tláloc, who was the rain-god, near him so that if necessary, the war god could compel the rain maker to exert his powers.

[25] Other names of Tláloc were Tlamacazqui ("Giver")[26] and Xoxouhqui ("Green One");[27] and (among the contemporary Nahua of Veracruz), Chaneco.

[16] The Tlálocan-bound dead were not cremated as was customary, but instead they were buried in the earth with seeds planted in their faces and blue paint covering their foreheads.

Cerro Tláloc was situated directly east of the pyramid, which is very in-line with classic Aztec architecture.

The children to be sacrificed were carried to Cerro Tláloc on litters strewn with flowers and feathers, while also being surrounded by dancers.

If, on the way to the shrine, these children cried, their tears were viewed as positive signs of imminent and abundant rains.

The flayed skins of sacrificial victims that had been worn by priests for the last twenty days were taken off and placed in these dark caverns.

[34] Evidence from the Codex Borbonicus suggests that Huey Tozotli was a commemoration of Centeotl, the god of maize.

Unlike many other female deities, Xochiquetzal maintains her youthful appearance and is often depicted in opulent attire and gold adornments.

[36] Research has shown that different orientations linked to Cerro Tláloc revealed a grouping of dates at the end of April and beginning of May associated with certain astronomical and meteorological events.

Archaeological, ethnohistoric, and ethnographic data indicate that these phenomena coincide with the sowing of maize in dry lands associated with agricultural sites.

[37] The precinct on the summit of the mountain contains 5 stones which are thought to represent Tláloc and his four Tlaloque, who are responsible for providing rain for the land.

It also features a structure that housed a statue of Tláloc in addition to idols of many different religious regions, such as the other sacred mountains.

Some 500 years ago weather conditions were slightly more severe, but the best time to climb the mountain was practically the same as today: October through December, and February until the beginning of May.

The date of the feast of Huey Tozotli celebrated atop Cerro Tláloc coincided with a period of the highest annual temperature, shortly before dangerous thunderstorms might block access to the summit.

[39] The first detailed account of Cerro Tláloc by Jim Rickards in 1929 was followed by visits or descriptions by other scholars.

[40] The current damage that is present at the top of Cerro Tláloc is thought to be likely of human destruction, rather than natural forces.

There also appears to have been a construction of a modern shrine that was built in the 1970s, which suggests that there was a recent/present attempt to conduct rituals on the mountain top.