Tobacco in the American colonies

It was distinct from rice, wheat, cotton and other cash crops in terms of agricultural demands, trade, slave labor, and plantation culture.

[10] This series of legislation on both sides of the Atlantic to exert control over the tobacco industry would continue until the American Revolution.

The number of man-hours needed to sustain larger operations increased, which forced planters to acquire and accommodate additional slave labor.

Furthermore, they had to secure larger initial loans from London, which increased pressure to produce a profitable crop and made them more financially vulnerable to natural disasters.

The slave population in the Chesapeake increased significantly during the 18th century due to the demand for cheap tobacco labor and a dwindling influx of indentured servants willing to migrate from England.

For the many farmers who seized the opportunity in the profitable tobacco enterprise, financial and personal anxiety mounted amidst stiff competition and falling prices.

Slaves, meanwhile, realized that the quality of a crop depended on their effort and began “foot-dragging”, or collectively slowing their pace in protest of the planters' extreme demands.

William Strickland, a wealthy colonial tobacco planter, remarked: Nothing can be conceived more inert than a slave; his unwilling labor is discovered in every step he takes; he moves not if he can avoid it; if the eyes of the overseer are off him, he sleeps…all is listless inactivity; all motion is evidently compulsory.

In the south, all economic activity was fed through a few heavily centralized markets, which favored large plantations that could bear the higher transportation costs.

Because of the diminished need for trained labor, families of slaves on cotton and rice plantations would often remain together, bought and sold as complete packages.

Individual life expectancies were generally shorter because their skill set was less refined and workers were easily replaced if killed.

Cotton and rice plantation owners employed a management technique called “tasking”, in which each slave would receive around one-half acre of land to tend individually with minimal supervision.

[17] In contrast, tobacco planters desired skilled male slaves, while women were mainly responsible for breeding and raising children.

Individual life expectancies for tobacco slaves were generally longer because their unique skills, honed over the course of many years in the field, proved indispensable to a planter’s success.

Unlike tasking, ganging was amenable to supervision and quality control and lacked an inherent measure of individual effort.

It was more common in the Chesapeake for a slave to work alongside his master, an arrangement unheard of in the strict vertical hierarchies of massive Southern plantations.

Whites and blacks were more deeply divided in the Deep South, and tasking allowed slave owners to arbitrarily replace individuals who did not meet expectations.

Breen writes “quite literally, the quality of a man’s tobacco often served as the measure of the man.”[19] Proficient planters, held in high regard by their peers, often exercised significant political clout in colonial governments.

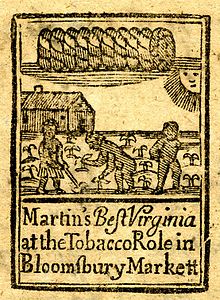

[9] By the mid 1620s tobacco became the most common commodity for bartering due to the increasing scarcity of gold and silver and the decreasing value of wampum from forgery and overproduction.

In order to help with accounting and standardizing trade, colonial government officials would rate tobacco and compare its weight into values of pounds, shillings, and pence.

[8] American tobacco planters, including Jefferson and George Washington, financed their plantations with sizeable loans from London.

Though never verified, Jefferson accused London merchants of unfairly depressing tobacco prices and forcing Virginia farmers to take on unsustainable debt loads.

In 1786, he remarked: A powerful engine for this [mercantile profiting] was the giving of good prices and credit to the planter till they got him more immersed in debt than he could pay without selling lands or slaves.

Planters whose operations collapsed were condemned as “sorry farmers” – unable to produce good crops and inept at managing their land, slaves, and assets.

[28]In conjunction with a global financial crisis and growing animosity toward British rule, tobacco interests helped unite disparate colonial players and produced some of the most vocal revolutionaries behind the call for American independence.

Lack of domestic market growth exacerbated these effects and a stagnated tobacco industry failed to fully recover as cotton became the main cash crop of the south going forward.

[29] According to historian Avery Craven, tobacco caused systematic soil depletion that shaped both agricultural development and the broader socio-economic order.

Agriculture in Virginia and Maryland relied on a single crop and exploitative practices, causing declining yields and exhausted lands.

The lack of proper plowing and cultivation methods led to destructive erosion, while continuous replanting depleted essential plant nutrients and encouraged harmful soil organisms.

As a result, expansion became necessary to maintain productivity, leading to social, economic, and political conflicts, as well as a decline in living standards.