Tolkien and the Classical World (book)

One area where Tolkien explicitly acknowledged classical influence was in his use of Plato's Atlantis legend in his tale of Númenor, the island civilisation that is lost beneath the waves.

Ross Clare examines classical historiographies of decline and fall by Herodotus, Thucydides and later Roman and Christian accounts to illuminate the fictional Númenor, the island civilisation that is lost beneath the waves.

Among the episodes he explores are the fall of the Elves, Lúthien's descent into the dark lord Morgoth's fortress of Angband, the Fellowship's journey through the dangerous tunnels of Moria, Gandalf's fight there with the Balrog, and Aragorn's taking the Paths of the Dead.

Austin M. Freeman discusses how Tolkien used Virgil's concept of pietas, pious duty, in the context of the fall of Gondolin and the assault on Minas Tirith.

He argues that Tolkien moves away from kleos (glory) to a combination of classical pietas, indomitable Northern will, and Christian pistis (faith), creating a Tolkienian virtue of estel (hope), meaning "active trust and loyalty".

Peter Astrup Sundt examines how Tolkien used the legend of Orpheus and Eurydice in his tale of Beren and Lúthien, and in the stories of Tom Bombadil and the Ents.

He calls Tolkien's use of the classical world "oblique", rejecting the conventional view that it was the origin of Western civilization in favour of northern Europe.

Shorter Remarks and Observations Alley Marie Jordan likens the rural culture of the hobbits of the Shire to that of the shepherds in Virgil's Eclogues.

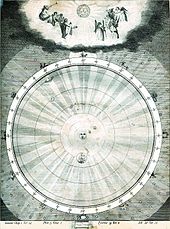

The Ainulindalë has been thought Christian, but, they argue, the medieval theology of the "music of the spheres" derives from Classical "Pythagorean and (Neo)Platonic" philosophies.

Afterword D. Graham J. Shipley sets Tolkien's response to the classics in context, discussing the way he adapts and reshapes concepts and stories from the sources he uses, and mentioning the various essays in the volume as he proceeds.

Those archetypes included "the wisdom of the lowly; the peripheral and the imperial; the human fear of death; the just ruler; and decline and redemption, both of individual[s] and of society."

[2][3][4][5] Larry J. Swain, writing in Mythlore, praises the essays in the collection as unusual in being entirely of good quality, examining a range of "classical sources and inspirations".

He finds the strongest essays to be those that directly discuss their classical source, like Sundt's Orpheus or Kleu's Atlantis, rather than generalising from other research.

[6] John Houghton, in Journal of Tolkien Research, gives the book a critical but not unfriendly review, pointing out some factual errors but calling it a "colossal volume".

[3] Joel D. Ruark, writing in VII, states that the essays mainly do "comparative analysis between Tolkien and the classics", enabling the reader to see the similarities and contrasts between the two.

Ruark feels that the book largely succeeds in "presenting and defending the position that the Greco-Roman classics influenced Tolkien’s thought and imagination throughout his life."

Hamby admires, too, the other introductory essay by Ross Clare, showing how the Delian League, like Tolkien's Númenor, grew into an autocracy.