Influences on Tolkien

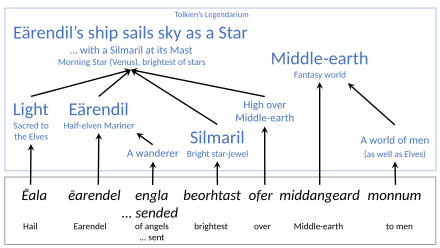

J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy books on Middle-earth, especially The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, drew on a wide array of influences including language, Christianity, mythology, archaeology, ancient and modern literature, and personal experience.

Some writers were certainly important to him, including the Arts and Crafts polymath William Morris, and he undoubtedly made use of some real place-names, such as Bag End, the name of his aunt's home.

[17] He made use of Beowulf, too, along with other Old English sources, for many aspects of the Riders of Rohan: for instance, their land was the Mark, a version of the Mercia where he lived, in Mercian dialect *Marc.

He once described The Lord of the Rings to his friend, the English Jesuit Father Robert Murray, as "a fundamentally religious and Catholic work, unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision.

"[32] Many theological themes underlie the narrative, including the battle of good versus evil, the triumph of humility over pride, and the activity of grace, as seen with Frodo's pity toward Gollum.

In addition the epic includes the themes of death and immortality, mercy and pity, resurrection, salvation, repentance, self-sacrifice, free will, justice, fellowship, authority and healing.

Tolkien mentions the Lord's Prayer, especially the line "And lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil" in connection with Frodo's struggles against the power of the One Ring.

While a student, Tolkien read the only available English translation[40][39] of the Völsunga saga, the 1870 rendering by William Morris of the Victorian Arts and Crafts movement and Icelandic scholar Eiríkur Magnússon.

The Elf Legolas describes Meduseld in a direct translation of line 311 of Beowulf (líxte se léoma ofer landa fela), "The light of it shines far over the land".

[48] The figure of Gandalf is based on the Norse deity Odin[49] in his incarnation as "The Wanderer", an old man with one eye, a long white beard, a wide brimmed hat, and a staff.

"[59] According to Humphrey Carpenter's biography of Tolkien, the author claimed to hold Wagner's interpretation of the relevant Germanic myths in contempt, even as a young man before reaching university.

[60] Some researchers take an intermediate position: that both the authors used the same sources, but that Tolkien was influenced by Wagner's development of the mythology,[61][62] especially the conception of the Ring as conferring world mastery.

They share a symbolical and literal association with fire, are both rebels against the gods' decrees and inventors of artefacts that were sources of light, or vessels to divine flame.

Tolkien wrote that he gave the Elvish language Sindarin "a linguistic character very like (though not identical with) Welsh ... because it seems to fit the rather 'Celtic' type of legends and stories told of its speakers".

[96] The Tuatha Dé Danann, semi-divine beings, invaded Ireland from across the sea, burning their ships when they arrived and fighting a fierce battle with the current inhabitants.

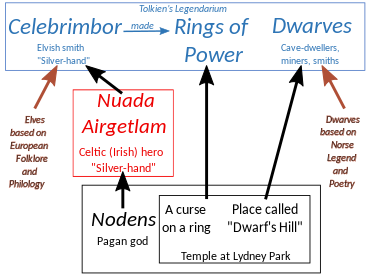

Another parallel can be seen between the loss of a hand by Maedhros, son of Fëanor, and the similar mutilation suffered by Nuada Airgetlám / Llud llaw Ereint ("Silver Hand/Arm") during the battle with the Firbolg.

In both, the male heroes make rash promises after having been stricken by the beauty of non-mortal maidens; both enlist the aid of great kings, Arthur and Finrod; both show rings that prove their identities; and both are set impossible tasks that include, directly or indirectly, the hunting and killing of ferocious beasts (the wild boars, Twrch Trwyth and Ysgithrywyn, and the wolf Carcharoth) with the help of a supernatural hound (Cafall and Huan).

[109][110] Such correlations are discussed in the posthumously published The Fall of Arthur; a section, "The Connection to the Quenta", explores Tolkien's use of Arthurian material in The Silmarillion.

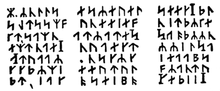

[114][115] Scholars including Nick Groom place Tolkien in the tradition of English antiquarianism, where 18th century authors like Thomas Chatterton, Thomas Percy, and William Stukeley created a wide variety of antique-seeming materials much as Tolkien did, including calligraphy, invented language, forged medieval manuscripts, genealogies, maps, heraldry, and a mass of invented paratexts such as notes and glossaries.

"[117] Sherwood argues that Tolkien intentionally set about improving on antiquarian forgery, eventually creating "the codes and conventions of modern fantasy literature".

[120] Postwar literary figures such as Anthony Burgess, Edwin Muir and Philip Toynbee sneered at The Lord of the Rings, but others like Naomi Mitchison and Iris Murdoch respected the work, and W. H. Auden championed it.

[120] Tolkien wrote that stories about "Red Indians" were his favourites as a boy; Shippey likens the Fellowship's trip downriver, from Lothlórien to Tol Brandir "with its canoes and portages", to James Fenimore Cooper's 1826 historical romance The Last of the Mohicans.

[124] Shippey writes that Éomer's riders of Rohan in the scene in the Eastemnet wheel and circle "round the strangers, weapons poised" in a way "more like the old movies' image of the Comanche or the Cheyenne than anything from English history".

[125] When interviewed, the only book Tolkien named as a favourite was Rider Haggard's adventure novel She: "I suppose as a boy She interested me as much as anything—like the Greek shard of Amyntas [Amenartas], which was the kind of machine by which everything got moving.

[120] Parallels between The Hobbit and Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth include a hidden runic message and a celestial alignment that direct the adventurers to the goals of their quests.

[134] Tolkien wrote of being impressed as a boy by Samuel Rutherford Crockett's historical fantasy novel The Black Douglas and of using it for the battle with the wargs in The Fellowship of the Ring;[135] critics have suggested other incidents and characters that it may have inspired,[136][137] but others have cautioned that the evidence is limited.

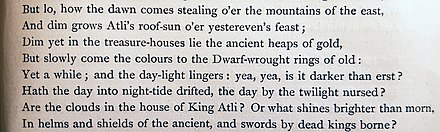

Tolkien wished to imitate the style and content of Morris's prose and poetry romances,[142] and made use of elements such as the Dead Marshes[143] and Mirkwood.

[166] Tolkien's fellow-Inkling C. S. Lewis, who fought in the 1917 Battle of Arras, wrote that The Lord of the Rings realistically portrayed "the very quality of the war my generation knew", including "the flying civilians, the lively, vivid friendships, the background of something like despair and the merry foreground, and such heavensent windfalls as a cache of tobacco 'salvaged' from a ruin".

"[169] Shippey adds that the group was "preoccupied" with "virtuous pagans", and that The Lord of the Rings is plainly a tale of such people in the dark past before Christian revelation.

All the same, Shippey writes, Tolkien's personal war experience was Manichean: evil seemed at least as powerful as good, and could easily have been victorious, a strand which can also be seen in Middle-earth.

It has been called "the catalyst for Tolkien's mythology". [ 5 ] [ 6 ]