Toll bridge

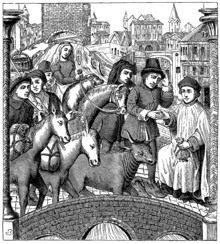

Having built a bridge, they hoped to recoup their investment by charging tolls for people, animals, vehicles, and goods to cross it.

Using interest on its capital assets, the trust now owns and runs all seven central London bridges at no cost to taxpayers or users.

In some instances, a quasi-governmental authority was formed, and toll revenue bonds were issued to raise funds for construction or operation (or both) of the facility.

Nakamura and Kockelman (2002) show that tolls are by nature regressive, shifting the burden of taxation disproportionately to the poor and middle classes.

[2] Electronic toll collection, branded under names such as EZ-Pass, SunPass, IPass, FasTrak, Treo, GoodToGo, and 407ETR, became increasingly prevalent to metropolitan areas in the 21st century.

Approvals were to be secured by government agencies before promulgating a paper form, website, survey or electronic submission that will impose an information collection burden on the general public.

However, the act did not anticipate and thus address the burden on the public associated with funding infrastructure via electronic toll collection instead of through more traditional forms of taxation.

In 1988, Jacksonville voters chose to eliminate all the toll booths and replace the revenue with a ½ cent sales tax increase.