Tomato bushy stunt virus

[2] It was first reported in tomatoes in 1935 and primarily affects vegetable crops, though it is not generally considered an economically significant plant pathogen.

[3][4] TBSV has a broad host range under experimental conditions and has been reported to infect over 120 plant species spanning 20 families.

Systemic infections can cause stunted growth, deformed or absent fruit, and damaged leaves; in agricultural settings yield can be significantly reduced.

[5] However, the closely related tombusvirus Cucumber necrosis virus (CNV) has been observed to be transmitted by Olpidium bornovanus zoospores, so transmission of TBSV by as-yet unknown vector remains a possibility.

[4][5] In experimental tests, the virus can survive passage through the human digestive system if consumed in food and will remain infectious; it has been hypothesized that spread through sewage could occur.

P33 is smaller and p92 is produced through ribosomal read-through of the p33 stop codon, resulting in a shared N-terminal amino acid sequence and a large excess of p33 relative to p92.

The p19 protein binds short interfering RNAs and prevents their incorporation into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), thereby allowing viral propagation in the host plant.

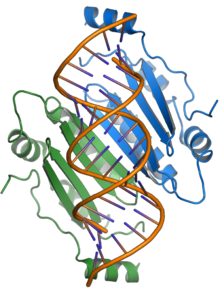

[4] A TBSV virion contains one copy of its positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome, which is linear and lacks a 3' polyadenine tail or 5' cap.

[4] Several long-distance interactions between linearly well-separated areas of the genome have been identified with functional importance in ensuring efficient replication.

[16] Defective interfering RNA (DI) molecules are RNAs that are produced from the viral genome but are not competent to infect cells on their own; instead they require coinfection with an intact "helper" virus.

TBSV infections often produce significant numbers of DIs from consistent parts of the genome under experimental conditions, but this behavior has not been observed in the wild.