Transformation of the Ottoman Empire

Demographic pressure[further explanation needed] in Anatolia contributed to the formation of bandit gangs, which by the 1590s coalesced under local warlords to launch a series of conflicts known as the Celali rebellions.

In Istanbul, changes in the nature of dynastic politics led to the abandonment of the Ottoman tradition of royal fratricide, and to a governmental system that relied much less upon the personal authority of the sultan.

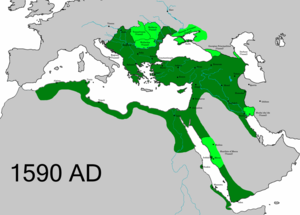

In comparison with earlier periods of Ottoman history, the empire's territory remained relatively stable, stretching from Algeria in the west to Iraq in the east, and from Arabia in the south to Hungary in the north.

The pace of expansion slowed during the second half of the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–66), as the Ottomans sought to consolidate the vast conquests carried out between 1514 and 1541,[nb 1] but did not come to an end.

[13] The empire's territory also included many smaller and often geographically isolated regions where the state's authority was weak, and local groups could exercise significant degrees of autonomy or even de facto independence.

Examples include the highlands of Yemen, the area of Mount Lebanon, mountainous regions of the Balkans such as Montenegro, and much of Kurdistan, where pre-Ottoman dynasties continued to rule under Ottoman authority.

[19] In the Balkan countryside the rate of conversion to Islam gradually increased until reaching a peak in the late seventeenth century, particularly affecting regions such as Albania, Macedonia,[24] Crete and Bulgaria.

[31] By the end of the seventeenth century, and largely a result of reforms carried out during the War of the Holy League, the central government's income had grown to 1 billion akçe, and continued to grow at an even more dramatic pace during the following period, now far outstripping inflation.

[34] Trade along the maritime routes of the Black Sea was severely disrupted from the late sixteenth century by the extensive raiding activity of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, who attacked towns along the Anatolian and Bulgarian coasts, and even established bases in the mouth of the Danube in order to plunder its shipping.

Protests, mutinies, and rebellions allowed the Janissaries to express their disapproval of imperial policy, and they frequently played a role in forming political coalitions within the Ottoman government.

[66] Although the empire experienced significant defeats and territorial loss in the 1683–99 War of the Holy League, this was caused not by military inferiority, but by the size and effective coordination of the Christian coalition, as well as the logistical challenges of warfare on multiple fronts.

[71] The Ottomans possessed a distinct superiority in logistical organization over their European rivals, who were typically forced to resort to ad hoc solutions or even outright plunder in order to keep their armies in good supply.

[75] By the mid-seventeenth century Ottoman Hungary contained approximately 130 fortresses of varying size and strength, ranging from small castles of less than a hundred men to major strongholds with garrisons in the thousands.

[89] Whereas sixteenth-century Ottoman admirals frequently began their careers as corsairs in North Africa, in the middle of the seventeenth century the admiralty was merely a prestigious office to be held by various statesmen who did not necessarily have any naval experience.

From 1695 to 1701 the Ottoman navy was placed under the command of Mezzo Morto Hüseyin Pasha, an experienced corsair from Algiers, who defeated the Venetian fleet in the Battle of the Oinousses Islands on 9 February 1695 and demonstrated the success of the previous decades' reforms.

[96] Kazıdadeli ideology centered on the Islamic invocation to "enjoin good and forbid wrong," leading them to oppose practices they perceived as "innovation" (bid'ah), in a manner roughly analogous to modern Wahhabism.

The result was a burst of new written works on rationalist topics, such as mathematics, logic, and dialectics, with many scholars tracing their intellectual lineage back to these Iranian and Kurdish immigrants.

Particularly after 1600, Ottoman writers shifted away from the Persianate style of previous generations, writing in a form of Turkish prose which was much less ornate in comparison with works produced in the sixteenth century.

Ottoman historians came to see themselves as problem-solvers, using their historical knowledge to offer solutions to contemporary issues, and for this they chose to write in a straightforward, easily understood vernacular form of Turkish.

War erupted with the Austrian Habsburgs in 1593 just as Anatolia experienced the first of several Celali Rebellions, in which rural bandit gangs grouped together under provincial warlords to wreak havoc on the countryside.

The cavalry army which had been supported by the Timar system during the sixteenth century was becoming obsolete as a result of the increasing importance of musket-wielding infantry, and the Ottomans sought to adapt to the changing times.

This aroused the anger of both the religious establishment as well as the Janissaries and Imperial Cavalry, and relations became particularly strained after the sultan's failed Polish campaign, in which the army felt it had been mistreated.

After their return to Istanbul, Osman II announced his desire to perform the pilgrimage to Mecca; in fact this was a plan to recruit a new and more loyal army in Anatolia, out of the bandit-mercenary forces which had taken part in the Celali Rebellions and the Ottomans' wars with the Habsburgs and Safavids.

[118] Turhan Sultan was henceforth in a secure position of power, but was unable to find an effective grand vizier, leaving the empire without a coherent policy with regard to the war with Venice.

In need of a change of policy, Turhan Hatice appointed the highly experienced Köprülü Mehmed Pasha as grand vizier, who immediately set forth on a drastic process of reform.

[120] While wintering in Edirne after leading a successful campaign to reconquer the islands, Köprülü extended his purge to the imperial cavalry, executing thousands of soldiers who showed any sign of disloyalty.

The empire was attacked simultaneously in Hungary, Podolia, and the Mediterranean region, while after 1686 their Crimean vassals, who under normal circumstances supported the Ottoman army with tens of thousands of cavalry, were continually distracted by the need to fend off Russian invasion.

[127] While territorial losses to the Habsburgs have at times been cited as evidence of military weakness, more recently historians have challenged this notion, arguing that Ottoman defeats were primarily a result of the sheer size of the coalition arrayed against them, and the logistical burden of fighting a war on multiple fronts.

Most significantly, in 1691 the standard unit of cizye assessment was shifted from the household to the individual, and in 1695 the sale of life-term tax farms known as malikâne was implemented, vastly increasing the empire's revenue.

After a final disastrous attempt to recover Hungary in the Austro-Turkish War (1716–1718) Ottoman foreign policy in Europe during the subsequent eighteenth century was generally peaceful and defensive, focused on the maintenance of a secure network of fortresses along the Danube frontier.