Treadwheel crane

The Roman Polyspaston crane, from Ancient Greek πολύσπαστον (polúspaston, “compound pulley”), when worked by four men at both sides of the winch, could lift 3000 kg.

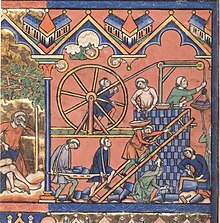

[3] The earliest reference to a treadwheel (magna rota) reappears in archival literature in France about 1225,[4] followed by an illuminated depiction in a manuscript of probably also French origin dating to 1240.

[5] In navigation, the earliest uses of harbor cranes are documented for Utrecht in 1244, Antwerp in 1263, Bruges in 1288 and Hamburg in 1291,[6] while in England the treadwheel is not recorded before 1331.

Typical areas of application were harbours, mines, and, in particular, building sites where the treadwheel crane played a pivotal role in the construction of the lofty Gothic cathedrals.

Nevertheless, both archival and pictorial sources of the time suggest that newly introduced machines like treadwheels or wheelbarrows did not completely replace more labor-intensive methods like ladders, hods and handbarrows.

[9] The exact process by which the treadwheel crane was reintroduced is not recorded,[4] although its return to construction sites has undoubtedly to be viewed in close connection with the simultaneous rise of Gothic architecture.

Alternatively, the medieval treadwheel may represent a deliberate reinvention of its Roman counterpart drawn from Vitruvius' De architectura which was available in many monastic libraries.

[11] Contrary to a popularly held belief, cranes on medieval building sites were neither placed on the extremely lightweight scaffolding used at the time nor on the thin walls of the Gothic churches which were incapable of supporting the weight of both hoisting machine and load.

[17] While ashlar blocks were directly lifted by sling, lewis or devil's clamp (German Teufelskralle), other objects were placed before in containers like pallets, baskets, wooden boxes or barrels.

[19] This curious absence is explained by the high friction force exercised by medieval treadwheels which normally prevented the wheel from accelerating beyond control.

[16] According to the "present state of knowledge" unknown in antiquity, stationary harbour cranes are considered a new development of the Middle Ages.

These cranes were placed docksides for the loading and unloading of cargo where they replaced or complemented older lifting methods like see-saws, winches and yards.

[20] Dockside cranes were not adopted in the Mediterranean region and the highly developed Italian ports where authorities continued to rely on the more labor-intensive method of unloading goods by ramps beyond the Middle Ages.

[22] Some harbour cranes were specialised at mounting masts to newly built sailing ships, such as in Danzig, Cologne and Bremen.