Tube Alloys

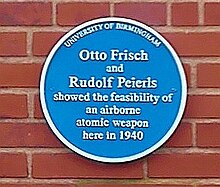

At the University of Birmingham, Rudolf Peierls and Otto Robert Frisch co-wrote a memorandum explaining that a small mass of pure uranium-235 could be used to produce a chain reaction in a bomb with the power of thousands of tons of TNT.

Due to the high costs for Britain while fighting a war within bombing range of its enemies, Tube Alloys was ultimately subsumed into the Manhattan Project by the Quebec Agreement with the United States.

They asked the French Minister of Armaments to obtain as much heavy water as possible from the only source, the large Norsk Hydro hydroelectric station at Vemork in Norway.

[23] At Cambridge, Nobel Prize in Physics laureates George Paget Thomson and William Lawrence Bragg wanted the government to take urgent action to acquire uranium ore.

In April 1939, he approached Sir Kenneth Pickthorn, the local Member of Parliament, who took their concerns to the Secretary of the Committee for Imperial Defence, Major General Hastings Ismay.

Since Union Minière management were friendly towards Britain, it was not considered worthwhile to acquire the uranium immediately, but Tizard's Committee on the Scientific Survey of Air Defence was directed to continue the research into the feasibility of atomic bombs.

Lord Cherwell had taken the matter to the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, who became the first national leader to approve a nuclear weapons programme on 30 August 1941.

Bretscher and Feather showed theoretically feasible grounds that element 94 would be fissile – readily split by both slow and fast neutrons with the added advantage of being chemically different from uranium.

[57] Halban's heavy water team from France continued its slow neutron research at Cambridge University; but the project was given a low priority since it was not considered relevant to bomb making.

Placzek proved to be a very capable group leader, and was generally regarded as the only member of the staff with the stature of the highest scientific rank and with close personal contacts with many key physicists involved in the Manhattan project.

He urged that Britain and the United States should inform the Soviet Union about the Manhattan Project in order to decrease the likelihood of its feeling threatened on the premise that the other nations were building a bomb behind its back.

[70][71] He reasoned that the longer the United States and Britain hid their nuclear advances, the more threatened the Russians would feel and the more inclined to speed up their effort to produce an atomic bomb of their own.

With the help of U.S. Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter, Bohr met on 26 August 1944 with the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was initially sympathetic to his ideas about controlling nuclear weapons.

[74] In August 1940, a British mission, led by Tizard and with members including Cockcroft, was sent to America to create relations and help advance the research towards war technology with the Americans.

Charles C. Lauritsen, a Caltech physicist working at the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), was in London during this time and was invited to sit in on a MAUD meeting.

[78] In August 1941, Mark Oliphant, the director of the physics department at the University of Birmingham and an original member of the MAUD Committee, was sent to the US to assist the NDRC on radar.

Coolidge was shocked when Oliphant told him the British had predicted that only ten kilograms of uranium-235 would be sufficient to supply a chain reaction effected by fast moving neutrons.

[80] While in America, Oliphant discovered that the chairman of the OSRD S-1 Section, Lyman Briggs, had locked away the MAUD reports transferred from Britain entailing the initial discoveries and had not informed the S-1 Committee members of all its findings.

[83] In October 1942, Bush and Conant convinced Roosevelt the United States should independently develop the atomic bomb project, despite an agreement of unrestricted scientific interchange between the US and Britain.

The Military Policy Committee (MPC) supported Bush's arguments and restricted access to the classified information which Britain could utilise to develop its atomic weapons programme, even if it slowed down the American efforts.

[86] The Americans stopped sharing any information on heavy water production, the method of electromagnetic separation, the physical or chemical properties of plutonium, the details of bomb design, or the facts about fast neutron reactions.

Dill died in Washington, D.C., in November 1944 and was replaced both as Chief of the British Joint Staff Mission and as a member of the Combined Policy Committee by Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland Wilson.

A compromise was reached, with Chadwick put in charge as Britain's technical advisor for the Combined Policy Committee, and as the head of the British Mission to the Manhattan Project.

The Americans said they would supply heavy water to the Montreal group only if it agreed to direct its research along the limited lines suggested by DuPont, its main contractor for reactor construction.

[99] He served as a member of the target committee established by Groves to select Japanese cities for atomic bombing,[100] and on Tinian with Project Alberta as a special consultant.

[104] The Soviet Union received details of British research from its atomic spies Klaus Fuchs, Engelbert Broda, Melita Norwood and John Cairncross, a member of the notorious Cambridge Five.

[125] In April 1950 an abandoned Second World War airfield, RAF Aldermaston in Berkshire, was selected as the permanent home for what became the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE).

[126] Penney assembled a team to initiate the work, firstly preparing a report describing the features, science and idea behind the American Fat Man implosion-type nuclear weapon.

[127] On 3 October 1952, under the code-name "Operation Hurricane", the first British nuclear device was successfully detonated in the Monte Bello Islands off the west coast of Australia.

[128] The Sputnik crisis and the development of the British hydrogen bomb led to the Atomic Energy Act being amended in 1958, and to a resumption of the nuclear Special Relationship between America and Britain under the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement.