Turbidity current

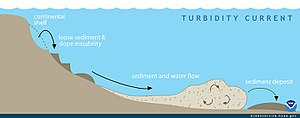

The driving force behind a turbidity current is gravity acting on the high density of the sediments temporarily suspended within a fluid.

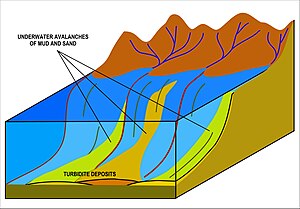

Seafloor turbidity currents are often the result of sediment-laden river outflows, and can sometimes be initiated by earthquakes, slumping and other soil disturbances.

In fresh water environments, such as lakes, the suspended sediment concentration needed to produce a hyperpycnal plume is quite low (1 kg/m3).

They follow the thalweg of the lake to the deepest area near the dam, where the sediments can affect the operation of the bottom outlet and the intake structures.

[9][10] Since the famous case of breakage of submarine cables by a turbidity current following the 1929 Grand Banks earthquake,[11] earthquake triggered turbidites have been investigated and verified along the Cascadia subduction Zone,[12] the Northern San Andreas Fault,[13] a number of European, Chilean and North American lakes,[14][15][16] Japanese lacustrine and offshore regions[17][18] and a variety of other settings.

[22] Sediment that has piled up at the top of the continental slope, particularly at the heads of submarine canyons can create turbidity current due to overloading, thus consequent slumping and sliding.

A buoyant sediment-laden river plume can induce a secondary turbidity current on the ocean floor by the process of convective sedimentation.

The resulting convective sedimentation leads to a rapid vertical transfer of material to the sloping lake or ocean bed, potentially forming a secondary turbidity current.

The vertical speed of the convective plumes can be much greater than the Stokes settling velocity of an individual particle of sediment.

[4] Large and fast-moving turbidity currents can carve gulleys and ravines into the ocean floor of continental margins and cause damage to artificial structures such as telecommunication cables on the seafloor.

[32] The lofted fluid carries fine sediment with it, forming a plume that rises to a level of neutral buoyancy (if in a stratified environment) or to the water surface, and spreads out.

[33] Experimental turbidity currents [34] and field observations [35] suggest that the shape of the lobe deposit formed by a lofting plume is narrower than for a similar non-lofting plume Prediction of erosion by turbidity currents, and of the distribution of turbidite deposits, such as their extent, thickness and grain size distribution, requires an understanding of the mechanisms of sediment transport and deposition, which in turn depends on the fluid dynamics of the currents.

The extreme complexity of most turbidite systems and beds has promoted the development of quantitative models of turbidity current behaviour inferred solely from their deposits.

In the long term, numerical techniques are most likely the best hope of understanding and predicting three-dimensional turbidity current processes and deposits.

In most cases, there are more variables than governing equations, and the models rely upon simplifying assumptions in order to achieve a result.

[5] Physical data from field observations, or more practical from experiments, are still required in order to test the simplifying assumptions necessary in mathematical models.

[39][40] The typical assumptions used along with the shallow-water models are: hydrostatic pressure field, clear fluid is not entrained (or detrained), and particle concentration does not depend on the vertical location.

Measurements such as, pressure field, energy budgets, vertical particle concentration and accurate deposit heights are a few to mention.