Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

In 1212, at the instigation of the Pope Innocent III, he finally became German king, initially as an anti-king to Otto IV, and in 1220 he was crowned emperor.

As a result of the escalating conflict between the Hohenstaufen dynasty and the papacy, the French prince Charles of Anjou was elevated to the Sicilian throne by Pope Clement IV in 1265.

Charles took power in 1266 through his victory over the Hohenstaufen king Manfred, who had initially administered Sicily as regent for his underage and absent nephew Conradin, but had then assumed the royal title himself.

The center of power was and remained Naples, which was magnificently expanded by the new Bourbon kings, while Sicily retained a secondary and semi-colonial status.

Charles attempted to rebuild the relatively weak state with enlightened reforms directed particularly against the influence of the Roman Catholic Church.

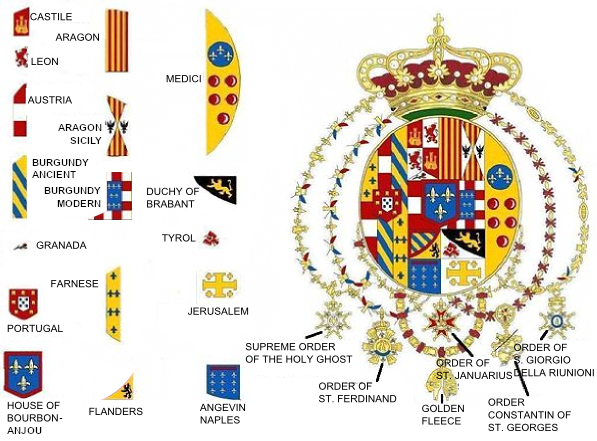

When this assertive monarch became King of Spain in 1759, he had to cede his former empire to his younger son Ferdinand IV, who founded the Bourbon-Sicily collateral line, because this crown could not be united with Naples-Sicily according to international treaties.

The Treaty of Casalanza restored Ferdinand IV of Bourbon to the throne of Naples and the island of Sicily (where the constitution of 1812 virtually had disempowered him) was returned to him.

The French novelist Henri de Stendhal, who visited Naples in 1817, called the kingdom "an absurd monarchy in the style of Philip II".

[9] His successor Ferdinand II declared a political amnesty and undertook steps to stimulate the economy, including reduction of taxation.

[10] King Ferdinand II appointed a liberal prime minister, broke off diplomatic relations with Austria and even declared war on the latter (7 April).

Although revolutionaries who had risen in several mainland cities outside Naples shortly after the Sicilians approved of the new measures (April 1848), Sicily continued with her revolution.

Faced with these differing reactions to his moves, King Ferdinand, using the Swiss Guard, took the initiative and ordered the suppression of the revolution in Naples (15 May) and by July the mainland was again under royal control and by September, also Messina.

The Kingdom pursued an economic policy of protectionism; the country's economy was mainly based on agriculture, the cities, especially Naples – with over 400,000 inhabitants, Italy's largest – "a center of consumption rather than of production" (Santore p. 163) and home to poverty most expressed by the masses of Lazzaroni, the poorest class.

[13] Until 1849, the political movement among the bourgeoisie, at times revolutionary, had been Neapolitan respectively Sicilian rather than Italian in its tendency; Sicily in 1848–1849 had striven for a higher degree of independence from Naples rather than for a unified Italy.

As public sentiment for Italian unification was rather low in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the country did not feature as an object of acquisition in the earlier plans of Piemont-Sardinia's prime minister Cavour.

On the orders of King Ferdinand I, who used the services of Antonio Niccolini, to rebuild the opera house within ten months as a traditional horseshoe-shaped auditorium with 1,444 seats, and a proscenium, 33.5m wide and 30m high.

Stendhal attended the second night of the inauguration and wrote: "There is nothing in all Europe, I won't say comparable to this theatre, but which gives the slightest idea of what it is like..., it dazzles the eyes, it enraptures the soul...".

During this period he wrote ten operas which were Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra (1815), La gazzetta, Otello, ossia il Moro di Venezia (1816), Armida (1817), Mosè in Egitto, Ricciardo e Zoraide (1818), Ermione, Bianca e Falliero, Eduardo e Cristina, La donna del lago (1819), Maometto II (1820), and Zelmira (1822), many premiered at the San Carlo.

An offer in 1822 from Domenico Barbaja, the impresario of the San Carlo, which followed the composer's ninth opera, led to Gaetano Donizetti's move to Naples and his residency there which lasted until the production of Caterina Cornaro in January 1844.

[34] The kingdom's few cities had little industry,[35] thus not providing the outlet for excess rural population found in northern Italy, France or Germany.

The figures above show that the population of the countryside rose at a faster rate than that of the city of Naples herself: rather unusual for a time when much of Europe was experiencing the Industrial Revolution.

The engineering factory of Pietrarsa was the largest industrial plant in the Italian peninsula,[37] producing tools, cannons, rails, and locomotives.

The growing British control and exploitation of the mining, refining, and transportation of sulfur, combined with the failure of this lucrative export to transform Sicily's backward and impoverished economy, led to the 'Sulfur Crisis' of 1840.

This was precipitated when King Ferdinand II granted a monopoly of the sulfur industry to a French company, in violation of an 1816 trade agreement with Britain.

Urban road conditions, compared to Northern Italy, did not comply with the best European standards;[42] by 1839, the main streets of Naples were gas-lit.

Efforts were made to tackle the tough mountainous terrain; Ferdinand II built the cliff-top road along the Sorrentine peninsula.

The conditions of the time in terms of social expenditure and public hygiene are mainly known today from the writings of the historian and journalist Raffaele De Cesare.

Most small municipalities had no sewers, and had an inadequate water supply due to the lack of public investment in the construction of pipes, which also meant that most private houses had no toilets.

Moreover, most rural inhabitants often lived in small old towns which, due to lack of social expenditure, became unhealthy, allowing many infectious diseases to spread rapidly.

While the municipal administration had few economic means to remedy the situation, the gentry often had whole sections of streets paved in front of the entrances of their homes.