Movable type

The world's first movable type printing technology for paper books was made of porcelain materials and was invented around 1040 AD in China during the Northern Song dynasty by the inventor Bi Sheng (990–1051).

[7] Around 1450, German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg invented the metal movable-type printing press, along with innovations in casting the type based on a matrix and hand mould.

The high quality and relatively low price of the Gutenberg Bible (1455) established the superiority of movable type in Europe and the use of printing presses spread rapidly.

The technique of imprinting multiple copies of symbols or glyphs with a master type punch made of hard metal first developed around 3000 BC in ancient Sumer.

[12] The enigmatic Minoan Phaistos Disc of c. 1800–1600 BC has been considered by one scholar as an early example of a body of text being reproduced with reusable characters: it may have been produced by pressing pre-formed hieroglyphic "seals" into the soft clay.

A few authors even view the disc as technically meeting all definitional criteria to represent an early incidence of movable-type printing.

Bi Sheng (畢昇) (990–1051) developed the first known movable-type system for printing in China around 1040 AD during the Northern Song dynasty, using ceramic materials.

[18] The ceramic movable type was also mentioned by Kublai Khan's counsellor Yao Shu, who convinced his pupil Yang Gu to print language primers using this method.

[3] The claim that Bi Sheng's clay types were "fragile" and "not practical for large-scale printing" and "short lived"[19] was refuted by later experiments.

Bao Shicheng (1775–1885) wrote that baked clay moveable type was "as hard and tough as horn"; experiments show that clay type, after being baked in an oven, becomes hard and difficult to break, such that it remains intact after being dropped from a height of two metres onto a marble floor.

[18][22]: 22 Bi Sheng (990–1051) of the Song dynasty also pioneered the use of wooden movable type around 1040 AD, as described by the Chinese scholar Shen Kuo (1031–1095).

[16][23] In 1298, Wang Zhen (王禎), a Yuan dynasty governmental official of Jingde County, Anhui Province, China, re-invented a method of making movable wooden types.

He made more than 30,000 wooden movable types and printed 100 copies of Records of Jingde County (《旌德縣志》), a book of more than 60,000 Chinese characters.

This system was later enhanced by pressing wooden blocks into sand and casting metal types from the depression in copper, bronze, iron or tin.

[17] In 1322, a Fenghua county officer Ma Chengde (馬称德) in Zhejiang, made 100,000 wooden movable types and printed the 43-volume Daxue Yanyi (《大學衍義》).

Even as late as 1733, a 2300-volume Wuying Palace Collected Gems Edition (《武英殿聚珍版叢書》) was printed with 253,500 wooden movable types on order of the Qianlong Emperor, and completed in one year.

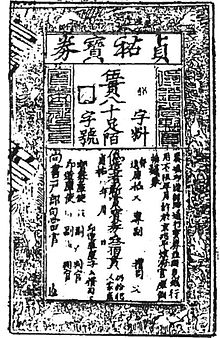

[25] At least 13 material finds in China indicate the invention of bronze movable type printing in China no later than the 12th century,[26] with the country producing large-scale bronze-plate-printed paper money and formal official documents issued by the Jin (1115–1234) and Southern Song (1127–1279) dynasties with embedded bronze metal types for anti-counterfeit markers.

A copper-block printed note dated between 1215 and 1216 in the collection of Luo Zhenyu's Pictorial Paper Money of the Four Dynasties, 1914, shows two special characters—one called Ziliao, the other called Zihao—for the purpose of preventing counterfeiting; over the Ziliao there is a small character (輶) printed with movable copper type, while over the Zihao there is an empty square hole—apparently the associated copper metal type was lost.

Another sample of Song dynasty money of the same period in the collection of the Shanghai Museum has two empty square holes above Ziliao as well as Zihou, due to the loss of the two copper movable types.

In 1725 the Qing dynasty government made 250,000 bronze movable-type characters and printed 64 sets of the encyclopedic Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China (《古今圖書集成》).

[34] Commenting on the invention of metallic types by Koreans, French scholar Henri-Jean Martin described this as "[extremely similar] to Gutenberg's".

The Joseon dynasty scholar Seong Hyeon (성현, 成俔, 1439–1504) records the following description of the Korean font-casting process: At first, one cuts letters in beech wood.

[31]A potential solution to the linguistic and cultural bottleneck that held back movable type in Korea for 200 years appeared in the early 15th century—a generation before Gutenberg would begin working on his own movable-type invention in Europe—when Sejong the Great devised a simplified alphabet of 24 characters (hangul) for use by the common people, which could have made the typecasting and compositing process more feasible.

[17] A "Confucian prohibition on the commercialization of printing" also obstructed the proliferation of movable type, restricting the distribution of books produced using the new method to the government.

[37] The technique was restricted to use by the royal foundry for official state publications only, where the focus was on reprinting Chinese classics lost in 1126 when Korea's libraries and palaces had perished in a conflict between dynasties.

[citation needed] Before Gutenberg, scribes copied books by hand on scrolls and paper, or print-makers printed texts from hand-carved wooden blocks.

Gutenberg and his associates developed oil-based inks ideally suited to printing with a press on paper, and the first Latin typefaces.

At the end of the 19th century there were only two typefoundries left in the Netherlands: Johan Enschedé & Zonen, at Haarlem, and Lettergieterij Amsterdam, voorheen Tetterode.

[53] In 1905 the Dutch governmental Algemeene Landsdrukkerij, later: "State-printery" (Staatsdrukkerij) decided during a reorganisation to use a standard type-height of 63 points Didot.

It was held in the printing shop in a job case, a drawer about 2 inches high, a yard wide, and about two feet deep, with many small compartments for the various letters and ligatures.